On a cloudy afternoon last week, a man mounted a busy overpass in Beijing’s Haidian university district, carrying a cardboard box and car tyres.

Wearing an orange worksuit and a yellow hard hat, he easily passed off as a construction worker.

But then, he unfurled two massive white banners covered in slogans written in red paint. He set the tyres on fire. As plumes of black smoke swirled around him, he picked up a loudhailer and repeatedly chanted:

“Go on strike at school and work, remove dictator and national traitor Xi Jinping! We want to eat, we want freedom, we want to vote!”

In an instant, the man pulled off one of the most significant acts of Chinese protest seen under Mr Xi’s rule, marring the triumphant start of the Chinese leader’s expected third term in power.

Tapping into a vein of discontent, it has ignited one of the most widespread social media storms – and censorship crackdowns – seen in recent years, leaving an enduring legacy in Chinese dissent.

Almost immediately after the protest began, pictures and videos of the event proliferated on social media platforms and messaging apps, a testament to how shocking the incident was to ordinary Chinese.

While public protests do happen in China, a political demonstration in the capital on the eve of an important Communist Party congress, blatantly insulting Xi Jinping, was unthinkable until now.

It exposed flaws in the supposedly tight security restrictions put in place for politically sensitive events – the man not only evaded initial detection but had enough time to attract the attention of passers-by before he was swiftly bundled into a police car.

It’s also attracted the attention of China’s censors who have relentlessly scrubbed photos and footage, and limited search results for a vast array of words including general terms such as “Beijing” and “bridge”.

This has led to an ongoing cat-and-mouse game with citizens, who have turned to AirDrop and file transfer services to share pictures, or come up with oblique terms such as “I saw it” to discuss the incident.

“This is really the strictest crackdown I have seen in years, in terms of the sheer breadth of things they are taking down. It’s overkill,” said censorship analyst Eric Liu with China Digital Times.

The protest has resonated deeply as it surfs a wave of simmering public frustration with zero-Covid, following high-profile incidents that have led many to question the stifling policy. This week the death of a 14-year-old in quarantine became the latest controversy to spark anger.

This frustration and fatigue have spread to almost every level of Chinese society, say observers.

With Shanghai and Beijing facing restrictions and endless rounds of Covid testing in recent months – the capital saw renewed measures on Thursday – “the middle and upper classes are really affected… it’s been a wake-up call for the privileged, they feel that the regime is hurting them too,” said Victoria Hui, a political scientist with the University of Notre Dame.

The protest has also mined a deep disquiet over the authoritarian direction China is heading towards – one banner declared “no leaders, we want votes” and “we are citizens, not slaves”.

Sociologist Ming-sho Ho of the National Taiwan University pointed out that since reformist Deng Xiaoping, China’s leaders have tended to govern in cycles of tightening and loosening restrictions.

“But Xi doesn’t have that cycle, it’s just a ratcheting-up of control. Zero-covid is just one of the symptoms of a system that is becoming more dictatorial with greater restriction of people’s liberties.”

All discussion and criticism of Mr Xi’s consolidation of power have been diligently shut down by censors, who even banned the Internet term “three-in-a-row with one key” – an allusion to his three terms.

But this enforced silence has been shattered by the bridge protest, which has amplified the discussion on the eve of his re-appointment, and possibly beyond.

“With its timing, this protest is now a symbol of Xi’s third term – people will make that association in the future,” said Prof Ho.

From Tank Man to Bridge Man

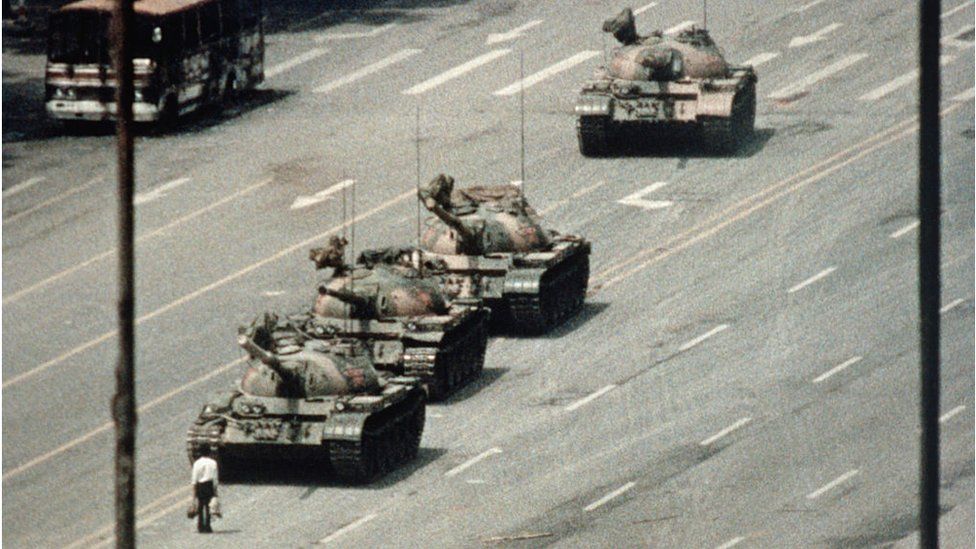

Some have dubbed the mysterious protester Bridge Man, a reference to the anonymous Tank Man demonstrator from the 1989 Tiananmen protests.

But experts in Chinese dissent say it is too early to tell if he will reach the same level of historical significance.

They point out there has been no clear image of the Bridge Man, and his demonstration was an isolated act of protest.

In contrast, the unknown protester at Tiananmen Square has been immortalised in news pictures, and appeared in a mass movement whose brutal legacy has become a taboo topic in China and haunts the Chinese consciousness to this day.

Many doubt Bridge Man’s actions would lead to a mass uprising. His calls for the public to go on strike and conduct various acts of civil disobedience during the party congress were ignored.

“This kind of individualised protest is far from the collective action that the Communist Party fears… and they have been able to stifle threats bigger than Bridge Man,” said political economy expert Ho-fung Hung from Johns Hopkins University, pointing to crackdowns on intellectuals, activists and lawyers in recent years.

If anything, the incident has alerted the party to this “seed of discontent” and gives them an excuse to tighten their grip even further, he added.

But in the age of social media, Bridge Man’s dramatic act of protest and his message are likely to reverberate long after his disappearance from public view.

Some Chinese are now countering the censors’ vigour with an equally matched determination to preserve Bridge Man’s legacy.

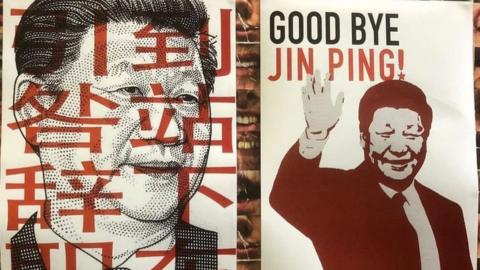

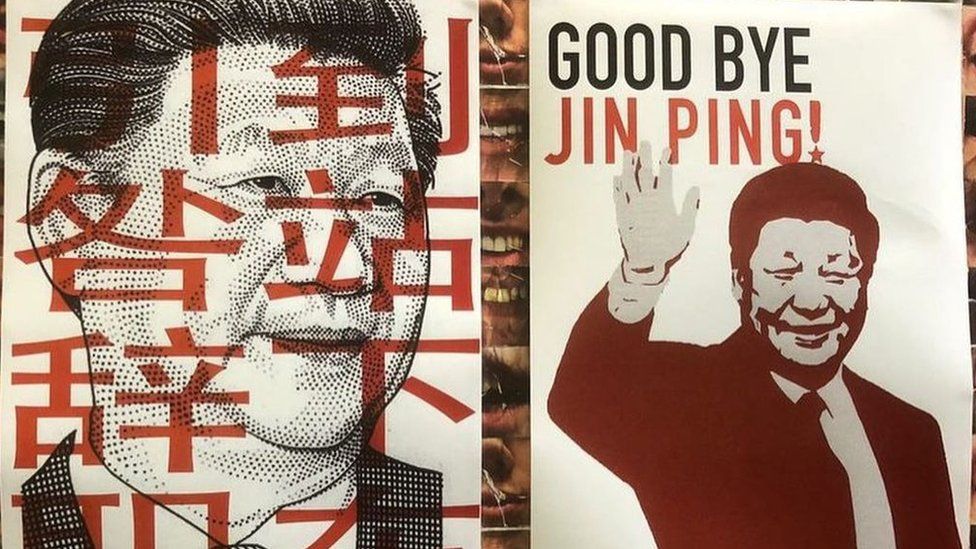

Activist groups have reproduced his political slogans online in posters and memes. Protest signs and graffiti have proliferated in universities, public walls, bridges, and even bathroom stalls in China and elsewhere around the world.

Many have also launched an online hunt for the mystery protester, zeroing in on a physicist and academic who appears to have left a digital trail of breadcrumbs for people to find. It includes an online manifesto, which some have made copies of and circulated online.

His Twitter accounts have been flooded with messages expressing admiration and vows to remember him.

Nobody knows for sure if he is indeed Bridge Man, but it is clear from the intensity of emotion that the mysterious protester has become a rallying symbol of hope.

“He has spoken up for everyone… I think especially after Tiananmen, people don’t want to forget someone like him,” said Dr Hui.

Now that he’s in the hands of the authorities, he is likely to face severe punishment, she noted.

“But his message is not going to die.”