In 1881, more than 250 million people answered a list of sometimes puzzling questions put to them by hundreds of enumerators, and were counted in British India’s first synchronised census.

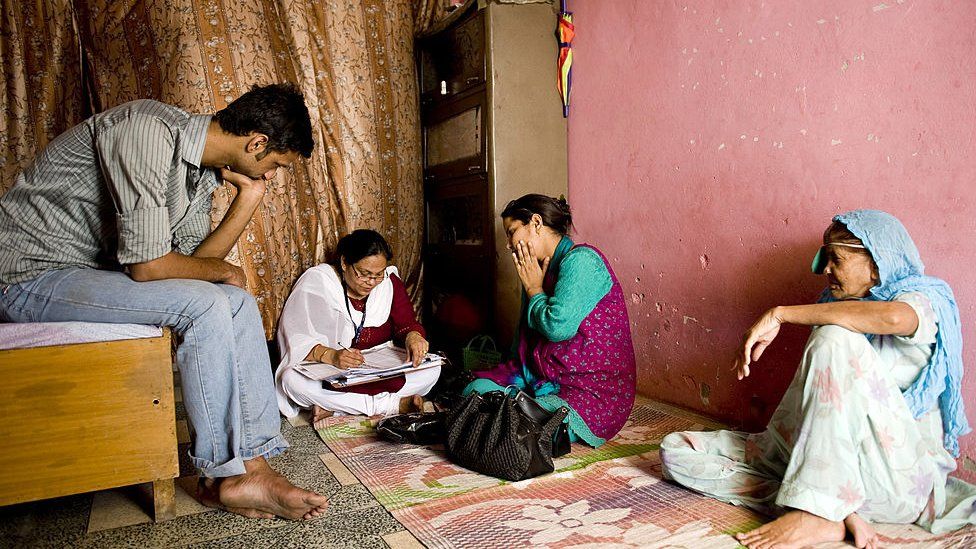

For the next 130 years, after independence and through wars and other crises, India kept its date with the census – once a decade, hundreds of thousands of enumerators visited every household in the country to gather information about people’s jobs, families, economic conditions, migration status and socio-cultural characteristics, among other parameters.

It’s an ambitious exercise which generates a trove of crucial data for administrators, policymakers, economists, demographers and anyone interested in knowing where the world’s second-most populous country (set to overtake China this year) is headed. It’s used to make decisions on everything from allocating federal funds to states and building schools to drawing constituency boundaries for elections.

But for the first time, India’s decennial census – which was set to be held in 2021 – has been delayed, with no clarity on when it will be held. Experts say they are worried about the consequences of this, which range from people being excluded from welfare schemes to incorrect resource allocation.

“The census is not simply a count of the number of people in a country. It provides invaluable data needed to make decisions at a micro level,” says Professor KP Kannan, a development economist who has worked extensively on poverty and inequality.

India’s census is conducted under the provisions of the Census Act, 1948, which doesn’t specify a time period for the government to conduct the exercise or release its results.

In 2020, India was set to begin the first phase of the census – in which housing data is collected – when the pandemic hit. The exercise was postponed while travel and movement were restricted and administrators dealt with more pressing issues.

Almost three years since then, most eligible Indians have got their Covid vaccinations, several states have held assembly elections and life has almost returned to normal.

But in December, the Narendra Modi government told parliament that “due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Census 2021 and the related field activities have been postponed until further orders”.

Weeks later, the Registrar General of India said that the deadline for freezing administrative boundaries had been extended to 30 June this year (states and union territories cannot make any changes to the boundaries of districts, towns and villages while the census is being conducted). The latest directive will push the survey to at least September.

Even then, observers don’t expect the exercise to take place before late 2024, as India is scheduled to hold its general election in the first part of next year.

Economist Dipa Sinha, who teaches at Delhi’s Ambedkar University, says an immediate consequence of this delay is on the public distribution system (PDS), through which the government supplies food grain and other essentials to the poor.

Since the government still depends on population figures from the 2011 census to determine who is eligible for aid, more than 100 million people are estimated to be excluded from the PDS, says Ms Sinha, quoting from research by economists Jean Dreze, Reetika Khera and Meghana Mungikar.

Their work used birth and death rates released by states and the home ministry’s population estimates to arrive at the number.

“The bigger the state, like Uttar Pradesh, the more people may have lost out on welfare schemes,” Ms Sinha says.

Even before the pandemic and the delay, the 2021 census was bound to be a controversial exercise.

The government had said that it would conduct a population survey to update the National Population Register (NPR) along with the census. But critics had alleged that the NPR would be a list from which “doubtful citizens” would be asked to prove they are Indian. The criticism came against the backdrop of a controversial 2019 citizenship law – which opponents say targets India’s 200 million-plus Muslims – that sparked months of protests across the country.

Several opposition and regional leaders had also demanded that the federal government conduct a caste census. Analysts believe this may cause fissures in the Hindu vote, which could hurt the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and spark demands for quotas from several groups.

Apart from the direct impact on welfare schemes, the census also provides the data set from which other crucial studies – such as the National Sample Survey (a series of surveys that collect information on all aspects of the economic life of citizens) and National Family Health Survey (a comprehensive household survey of health and social indicators) – draw their samples.

While states and some ministries could bridge part of the data gap by conducting their own surveys – Bihar, for instance, is currently doing a caste census which will throw light on several other indicators – these can only be stopgap measures, experts say.

“There is no alternative to a credible national survey like the census, which undertakes complete enumeration of everyone in the country,” says Prof Kannan, pointing out that states are not watertight compartments where the population stays constant.

The uncertainty over the census also comes amid the federal government facing questions over quality of data and delay in the release of several surveys.

In 2019, for instance, the government said it wouldn’t release a key survey result for 2017-18 due to “data quality issues” after a media report said the study showed a fall in consumer spending for the first time in more than four decades. More than 200 economists, academics and journalists – including Nobel prize-winning economist Angus Deaton – issued a statement asking the government to release the data and raised larger concerns.

“It is of fundamental importance for the nation that statistical institutions are kept independent of political interference, and are allowed to release all data independently,” the statement said.

In August last year, a parliamentary panel questioned the government over an “undue delay” in the release of India’s seventh economic census, which counts all economic enterprises in the country.

“There is an overall data issue in the country,” Ms Sinha says.

Prof Kannan points out that in the past, India helped other developing countries set up their own censuses, a matter of national pride.

“India’s reputation could suffer internationally as a result of declining data integrity,” he says.

Read more India stories from the BBC: