Speeding toward a ChatGPT-powered Wall Street

Artificial Intelligence-powered tools, such as ChatGPT, have the potential to revolutionize the efficiency, effectiveness and speed of the work humans do.

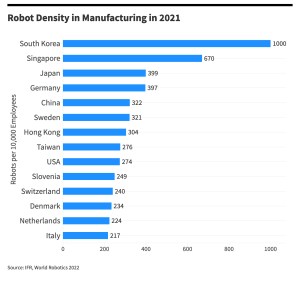

And this is true in financial markets as much as in sectors like health care, manufacturing and pretty much every other aspect of our lives.

I’ve been researching financial markets and algorithmic trading for 14 years. While AI offers lots of benefits, the growing use of these technologies in financial markets also points to potential perils. A look at Wall Street’s past efforts to speed up trading by embracing computers and AI offers important lessons on the implications of using them for decision-making.

Program trading fuelled Black Monday

In the early 1980s, fueled by advancements in technology and financial innovations such as derivatives, institutional investors began using computer programs to execute trades based on predefined rules and algorithms. This helped them complete large trades quickly and efficiently.

Back then, these algorithms were relatively simple and were primarily used for so-called index arbitrage, which involves trying to profit from discrepancies between the price of a stock index – like the S&P 500 – and that of the stocks it’s composed of.

As technology advanced and more data became available, this kind of program trading became increasingly sophisticated, with algorithms able to analyze complex market data and execute trades based on a wide range of factors. These program traders continued to grow in number on the largey unregulated trading freeways – on which over a trillion dollars worth of assets change hands every day – causing market volatility to increase dramatically.

Eventually this resulted in the massive stock market crash in 1987 known as Black Monday. The Dow Jones Industrial Average suffered what was at the time the biggest percentage drop in its history, and the pain spread throughout the globe.

In response, regulatory authorities implemented a number of measures to restrict the use of program trading, including circuit breakers that halt trading when there are significant market swings and other limits. But despite these measures, program trading continued to grow in popularity in the years following the crash.

HFT: Program trading on steroids

Fast forward 15 years, to 2002, when the New York Stock Exchange introduced a fully automated trading system. As a result, program traders gave way to more sophisticated automations with much more advanced technology: High-frequency trading.

HFT uses computer programs to analyze market data and execute trades at extremely high speeds. Unlike program traders that bought and sold baskets of securities over time to take advantage of an arbitrage opportunity – a difference in price of similar securities that can be exploited for profit – high-frequency traders use powerful computers and high-speed networks to analyze market data and execute trades at lightning-fast speeds.

High-frequency traders can conduct trades in approximately one 64-millionth of a second, compared with the several seconds it took traders in the 1980s.

These trades are typically very short term in nature and may involve buying and selling the same security multiple times in a matter of nanoseconds. AI algorithms analyze large amounts of data in real time and identify patterns and trends that are not immediately apparent to human traders. This helps traders make better decisions and execute trades at a faster pace than would be possible manually.

Another important application of AI in HFT is natural language processing, which involves analyzing and interpreting human language data such as news articles and social media posts. By analyzing this data, traders can gain valuable insights into market sentiment and adjust their trading strategies accordingly.

Benefits of AI trading

These AI-based, high-frequency traders operate very differently than people do.

The human brain is slow, inaccurate and forgetful. It is incapable of quick, high-precision, floating-point arithmetic needed for analyzing huge volumes of data for identifying trade signals. Computers are millions of times faster, with essentially infallible memory, perfect attention and limitless capability for analyzing large volumes of data in split milliseconds.

And, so, just like most technologies, HFT provides several benefits to stock markets.

These traders typically buy and sell assets at prices very close to the market price, which means they don’t charge investors high fees. This helps ensure that there are always buyers and sellers in the market, which in turn helps to stabilize prices and reduce the potential for sudden price swings.

High-frequency trading can also help to reduce the impact of market inefficiencies by quickly identifying and exploiting mispricing in the market. For example, HFT algorithms can detect when a particular stock is undervalued or overvalued and execute trades to take advantage of these discrepancies. By doing so, this kind of trading can help to correct market inefficiencies and ensure that assets are priced more accurately.

The downsides

But speed and efficiency can also cause harm.

HFT algorithms can react so quickly to news events and other market signals that they can cause sudden spikes or drops in asset prices.

Additionally, HFT financial firms are able to use their speed and technology to gain an unfair advantage over other traders, further distorting market signals. The volatility created by these extremely sophisticated AI-powered trading beasts led to the so-called flash crash in May 2010, when stocks plunged and then recovered in a matter of minutes – erasing and then restoring about $1 trillion in market value.

Since then, volatile markets have become the new normal. In 2016 research, two co-authors and I found that volatility – a measure of how rapidly and unpredictably prices move up and down – increased significantly after the introduction of HFT.

The speed and efficiency with which high-frequency traders analyze the data mean that even a small change in market conditions can trigger a large number of trades, leading to sudden price swings and increased volatility.

In addition, research I published with several other colleagues in 2021 shows that most high-frequency traders use similar algorithms, which increases the risk of market failure. That’s because as the number of these traders increases in the marketplace, the similarity in these algorithms can lead to similar trading decisions.

This means that all of the high-frequency traders might trade on the same side of the market if their algorithms release similar trading signals. That is, they all might try to sell in case of negative news or buy in case of positive news. If there is no one to take the other side of the trade, markets can fail.

Enter ChatGPT

That brings us to a new world of ChatGPT-powered trading algorithms and similar programs. They could take the problem of too many traders on the same side of a deal and make it even worse.

In general, humans, left to their own devices, will tend to make a diverse range of decisions. But if everyone’s deriving their decisions from a similar artificial intelligence, this can limit the diversity of opinion.

Consider an extreme, nonfinancial situation in which everyone depends on ChatGPT to decide on the best computer to buy. Consumers are already very prone to herding behavior, in which they tend to buy the same products and models. For example, reviews on Yelp, Amazon and so on motivate consumers to pick among a few top choices.

Since decisions made by the generative AI-powered chatbot are based on past training data, there would be a similarity in the decisions suggested by the chatbot. It is highly likely that ChatGPT would suggest the same brand and model to everyone. This might take herding to a whole new level and could lead to shortages in certain products and service as well as severe price spikes.

This becomes more problematic when the AI making the decisions is informed by biased and incorrect information. AI algorithms can reinforce existing biases when systems are trained on biased, old or limited data sets. And ChatGPT and similar tools have been criticized for making factual errors.

In addition, since market crashes are relatively rare, there isn’t much data on them. Since generative AIs depend on data training to learn, their lack of knowledge about them could make them more likely to happen.

For now, at least, it seems most banks won’t be allowing their employees to take advantage of ChatGPT and similar tools. Citigroup, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs and several other lenders have already banned their use on trading-room floors, citing privacy concerns.

But I strongly believe banks will eventually embrace generative AI, once they resolve concerns they have with it. The potential gains are too significant to pass up – and there’s a risk of being left behind by rivals.

But the risks to financial markets, the global economy and everyone are also great, so I hope they tread carefully.

Pawan Jain, Assistant Professor of Finance, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.