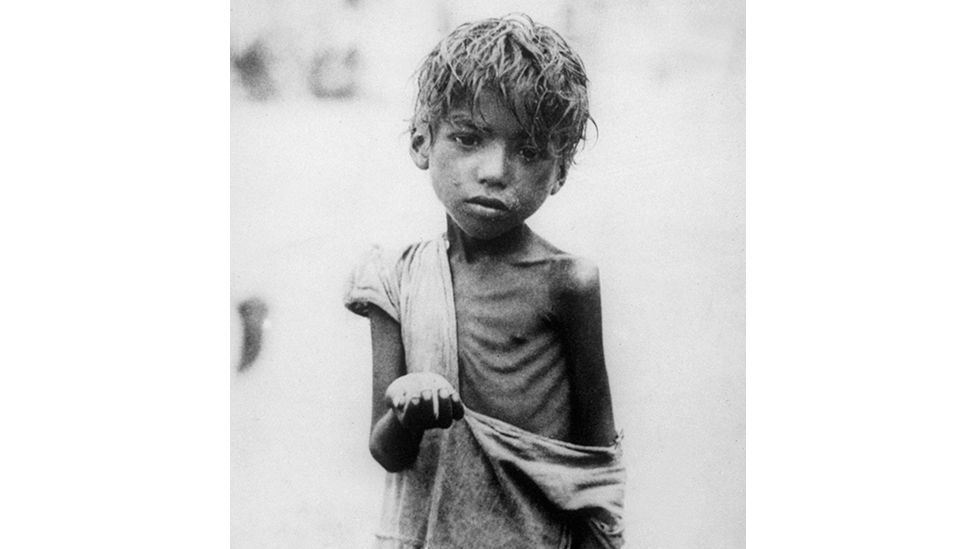

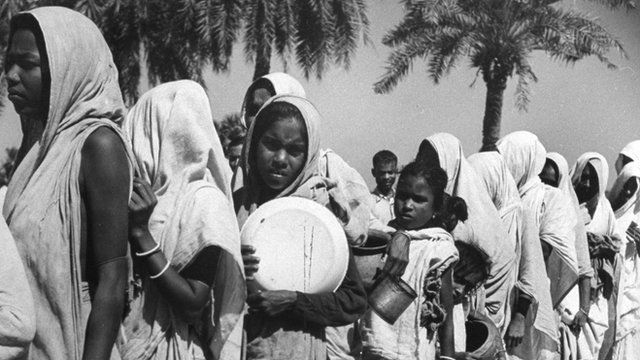

The Bengal famine of 1943 killed more than three million people in eastern India. It was one of the worst losses of civilian life on the Allied side in World War Two.

There is no memorial, museum, or even a plaque, anywhere in the world to the people who died. However, a few survivors remain, and one man is determined to gather their stories before it is too late.

‘Hunger stalked us’

“Many people sold their boys and girls for a little rice. Many wives and young women ran off, hand-in-hand with men they knew or didn’t know.”

Bijoykrishna Tripathi is describing the desperate measures people took to find food during the Bengal famine.

He is not sure of his exact age, but his voter card says he is 112. Bijoykrishna is one of the last people to remember the disaster.

He talks faintly and slowly about growing up in Midnapore, a district in Bengal. Rice was the staple food, and he remembers its price rising “by leaps and bounds” in the summer of 1942.

Then came the cyclone of October that year, which blew the roof of his house off and destroyed that year’s rice crop. Rice soon became unaffordable for his family.

“Hunger stalked us. Hunger and epidemics. People of all ages began to die.”

Bijoykrishna remembers some food relief, but says it was inadequate.

“Everyone had to live with half-empty stomachs,” he says. “Since there was nothing to eat, many people in the village died. People started looting, searching for food.”

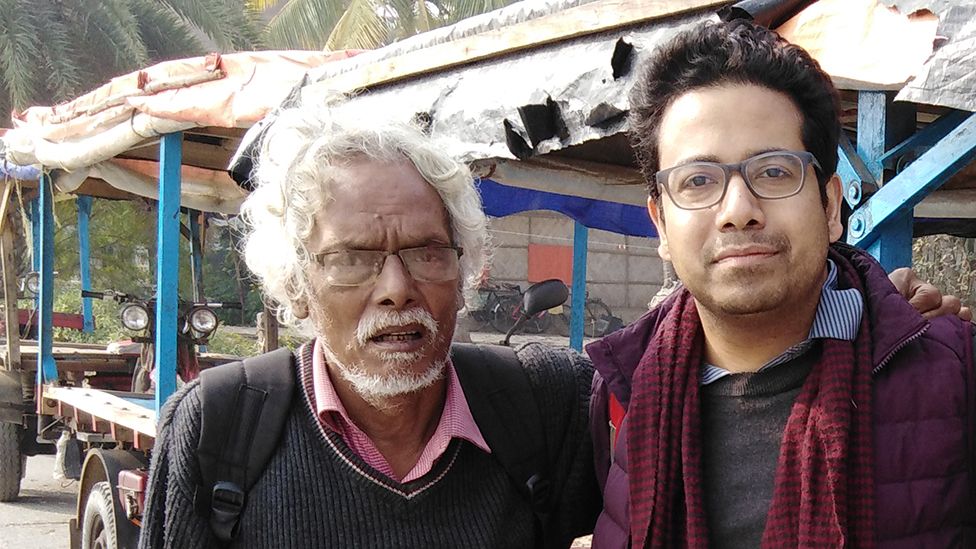

Listening to him on his veranda are four generations of his family. Also with them is Sailen Sarkar who, for the past few years, has been travelling around the Bengali countryside, gathering first-hand accounts from survivors of the devastating famine.

The 72-year-old is warm, has a youthful air, and smiles easily. You can see why people like Bijoykrishna open up to him. He travels around the countryside in his open-toed sandals, whatever the weather, with his backpack and a supply of roll-up cigarettes. He is old-school, taking down the testimonies with pen and paper.

Sailen says he first became “obsessed” by the Bengal famine because of a family photograph album. He would flick through it as a little boy in Calcutta (now Kolkata), staring at the photographs of emaciated people.

The pictures had been taken by his father, who had been involved with a local Indian charity, giving out relief during the famine. Sailen says his father was a poor man. “In my childhood I saw the terror of starvation in his eyes,” he says.

However, it was not until 2013 when Sailen – now a retired teacher – started his quest. While walking in Midnapore, he fell into conversation about the famine with an 86-year-old man.

Sripaticharan Samanta, like Bijoykrishna, also remembered the devastating cyclone. Life was already getting harder by that point, and the price of rice had been increasing steadily.

By October 1942 he was eating one small meal of rice a day. Then the storm hit.

Sripaticharan remembered how the price of rice skyrocketed after the cyclone, and how traders bought up whatever was left at any price.

“Soon there was no rice in our village,” he told Sailen. “People lived off saved stocks for a while but started to sell off their lands just to have rice to eat.”

After the storm, his family’s household rice reserves lasted for only a few days, then ran out.

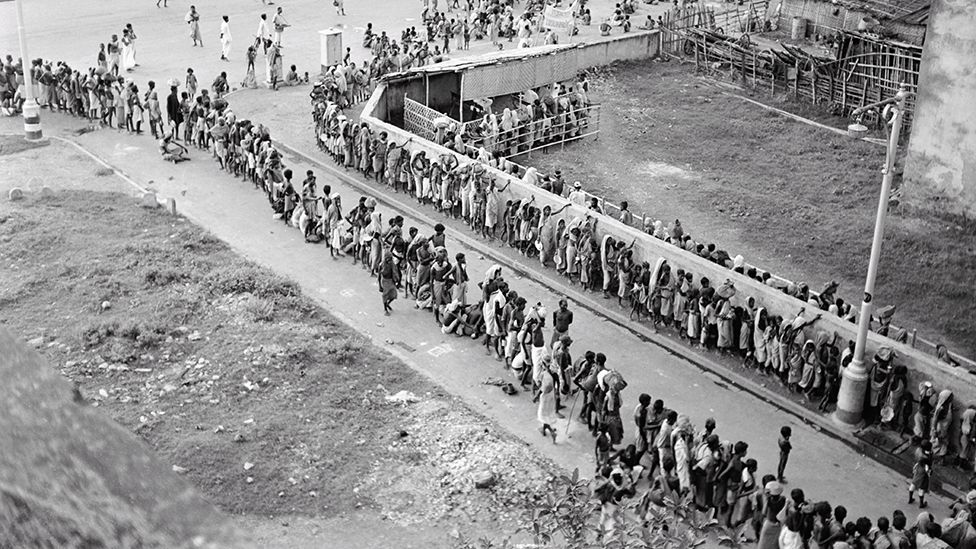

Like tens of thousands of others, Sripaticharan left the countryside for the city – in his case, Calcutta – in the hope of relief. He was lucky – he had a family member to stay with – and he survived. But many were not so fortunate, collapsing on roadsides, around dustbins, and dying on the pavements – strangers in a city they thought would help them.

Three Million

The devastating story of the Bengal Famine of 1943 in British India, where at least three million people died, told for the first time by the eyewitnesses to it.

A forgotten fate

The causes of the famine are many and complex, and continue to be widely debated.

In 1942, rice supplies in Bengal were under intense pressure.

Burma – which bordered Bengal – was invaded by Japan early in the year, and rice imports from that country stopped abruptly.

Bengal now found itself near the front line and Calcutta became host to hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers and workers in wartime industries, increasing the demand for rice. Wartime inflation was rife, putting the price of rice out of reach for millions who were already struggling.

Meanwhile, British fears that the Japanese would attempt to invade east India prompted a “denial” policy – this involved confiscating surplus rice and boats from towns and villages in the Bengal Delta. The aim was to deny food supplies and transport to any advancing force, but it disrupted the already fragile local economy, and caused prices to rise further. Rice was hoarded for food security, but often for profit.

To cap it all, the devastating cyclone of October 1942 destroyed many rice crops, with crop disease ruining much of the rest.

There is a long-running and often heated debate over culpability for this humanitarian catastrophe and in particular whether British Prime Minister Winston Churchill did enough – in the middle of a war on many fronts – to alleviate the crisis and help Indians, once he knew about its severity.

Relief efforts started to be put into place by the end of 1943 with the arrival of a new viceroy, Field Marshall Lord Wavell. But many had already died by then.

‘A living archive’

Discussions over the causes and who was to blame have often overshadowed the stories of the survivors.

Sailen has now gathered more than 60 eyewitness accounts. In most cases, the people he says he talked to were uneducated, and had rarely spoken about the famine or been asked, even by their own family.

There is no archive dedicated to collecting survivor testimonies. Sailen believes their stories were overlooked because they were the poorest and most vulnerable in society.

“It is as if they were all waiting. If only someone would listen to their words,” he says.

Niratan Bedwa was 100 when Sailen met her. She described the agony of mothers trying to look after their children.

“Mothers didn’t have any breast milk. Their bodies had become all bones, no flesh,” she said. “Many children died at birth, their mothers too. Even those that were born healthy died young from hunger. Lots of women killed themselves at that time.”

She also told Sailen that some wives ran off with other men if their husbands could not feed them. “At that time people weren’t so scandalised by these things,” she said. “When you have no rice in your belly, and no-one who can feed you, who is going to judge you anyway?”

Sailen also talked to people who had profited from the famine. One man admitted that he bought up a lot of land “in exchange for rice and dal or a little money”. He also told Sailen that another household died without an heir, so he took the land as his own.

Kushanava Choudhury, a Bengali-American writer, accompanied Sailen on one of his visits to meet some of the survivors.

“We didn’t have to search for them – they weren’t hiding, they were all in plain sight, in villages all across West Bengal and Bangladesh, who were just sitting there as the largest archive in the world,” he says.

“Nobody had bothered to talk to them. I felt tremendous shame about that.”

The famine is remembered in iconic Indian films, and photographs and sketches from the time, but Kushanava says it has rarely been recalled in the voice of the victims or survivors: “The story is written by the people who it didn’t affect. It’s a curious phenomena via who tells stories and who constructs reality.”

Prof Shruti Kapila of Cambridge University says the fate of the famine victims has perhaps been overshadowed because the 1940s were, for India, a “decade of death”.

In 1946, Calcutta was the scene of massive communal riots in which thousands died.

A year later, the British left, dividing the country into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. There was joy at independence, but the partition was bloody and traumatic – more than a million people died as people turned on those of the other religion. Up to 12 million people crossed the new border.

Bengal itself was divided between India and East Pakistan, which would later become Bangladesh.

Prof Kapila says of this period, “There’s very little punctuation to a series of mass death events that take place. And that’s why I would think that the Bengal famine in a way struggles to find its own place in that narrative.”

But while the victims – in their own words – have not been widely heard, she says famine and hunger is seen by many Indians as one of the enduring legacies of Empire.

Eighty years on, there are only a handful of survivors. Sailen remembers going to talk to one man, Anangamohan Das, who was then 91. On hearing why he was there, the man was quiet for some time. Tears then streamed down his sunken cheeks as he said, “Why did you come so late?”

But the dozens of accounts Sailen has collected are a small testament to an event that left millions dead, and millions more lives changed.

“When you want to forget your history,” he says, “you want to forget everything.” Sailen is determined this should not happen.

Related Topics

-

-

21 July 2020

-

-

-

1 April 2015

-