By Kavita Puri, Presenter, Three Million podcast

BBC

BBC” I feel tremendous guilt about what happened”, Susannah Herbert tells me.

At the top of the 1943 drought, which claimed the lives of at least three million people, her father was the government of Bengal, in British India.

She is just learning about his important role in the disaster and is dealing with a complicated household legacy.

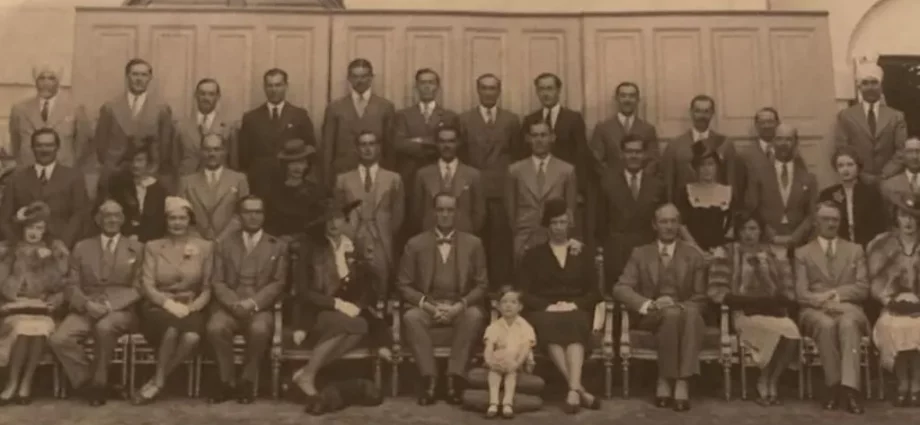

She is holding a 1940 photo when we first meet. It’s Christmas Day at the president’s mansion in Bengal. It’s official, with individuals sitting in columns, in their robes, staring directly into camera.

In the front are the officials- Viceroy Linlithgow, one of the most significant colonial characters in India, and her uncle Sir John Herbert, Bengal’s government.

At their feet is a little child, in a light shirt and shorts, leg- large socks and gleaming shoes. It’s Susannah’s parents.

Susannah Herbert

Susannah HerbertHe had only told her a few of his experiences growing up in India, such as when Father Christmas arrived on an rhino, but not much more.

But much was spoken of her father, who died in soon 1943.

There are many and varied reasons for the hunger. While John Herbert was Bengal’s most significant imperial number, he also was a member of a larger colonial architecture. He reported to his leaders in Delhi, who reported to theirs in London.

Herbert “was the colonial official many directly linked to the drought because he was the chief professional of the state of Bengal at the time,” according to Dr. Janam Mukherjee, an historian and author of Hungry Bengal.

In thousands of villages, boats and grain, the main meal, were taken or destroyed as part of one of the policies he carried out during World War Two, known as “denial” or “denial.” Due to the fear of a Chinese invasion, the goal was to prevent the enemy from using native resources to advance into India.

However, the imperial scheme was fatal for the previously fragile local market. Fishermen could n’t go to sea, farmers were n’t able to go upstream to their plots, and artisans were unable to get their goods to market. Critically, corn could not be moved about.

Herbert home

Herbert homeThe colonial government in Delhi was printing money to pay for the extensive war efforts on the Eastern before, but inflation was now great. The tens of thousands of Military men in Kolkata, next Calcutta, were putting up with limited food sources.

Rice goods from Burma to Bengal had stopped after it fell to the Chinese. Rice was hoarded, usually for income. And a fatal storm hit, wiping out many of Bengal’s grain crop.

At the time, repeated requests for food exports to the battle government and Prime Minister Winston Churchill were denied or half heeded.

The figures who died are enormous. I wondered why Susannah, the daughter of Bengal’s government, felt sorrow so many years later.

She tries to explain. There was something about beautiful about having a link to the British Empire when I was younger.

She says she used to acquire a lot of her father’s old garments. ” There were silk hats, with a nametape saying’ Made in American India ‘.

And now when I see them at the back of a cupboard, I kind of growl and ask,” Why would I even want to wear these things?” Because the label’s words” American India” seem inappropriate to wear right now, it seems inappropriate.

Herbert home

Herbert homeSusannah is determined to know more about her father’s life in American India, and to make sense of things.

She is going through layers of her parents ‘ documents at the Herbert library in the family residence in Wales and is reading everything she can about the Bengal hunger. They’re kept in a climate- managed area, and an archive visits once a month.

She starts to understand more about her uncle”. There is without a doubt that the plans he developed and implemented significantly increased the scope and influence of the hunger.

” He had knowledge, he had honour. And he ought not to have been given the task of ensuring the safety of 60 million people living in a remote section of the British Empire. He really should not have been appointed”.

In the home library she found a text from Lady Mary, her mother, written to her father in 1939, on reading he had been offered the job of government. It’s a notice of pros and cons. She allegedly stated that she did n’t want them to leave, but she claims that she would accept any action he might have taken.

” You read them]the letters ] with hindsight, you read them knowing what the writer and reader did not know. If you could reach out to the past, you’d say: do n’t do it. Do n’t go, do n’t go to India. You wo n’t do a good job,” says no.

Susannah Herbert has had a lot of thorough inquiries about her father over the course of the weeks I have been following his journey into the past.

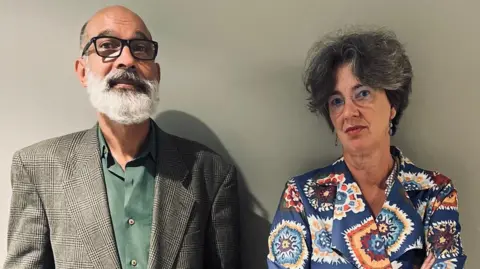

She has been willing to join Janam Mukherjee, the writer, to question him immediately. They meet in June.

Janam admits that he never imagined sitting in front of the daughter of John Herbert.

Susannah wants to know why her father, a statewide MP and state whip, was appointed in the first place, when he had almost no knowledge of American politics, beyond a short spell in Delhi as a young officer.

” It’s part and parcel of colonialism and stems from an idea of supremacy”, Janam explains.

” Some MP who has no imperial experience, who has no verbal abilities, who has not worked in a political structure outside of Britain, can just go and live the governor’s residence in Kolkata, and make judgments about an entire population of people that he knows everything about”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven his senior citizens in Delhi, including Viceroy Linlithgow, appear to have doubted his competence, despite the fact that he was not well-known among the elected Indian politicians in Bengal.

” Linlithgow called him the weakest governor in India. They, in fact, were interested in removing him, but they were worried about how that might be received”, says Janam.

” That is hard listening”, Susannah replies.

I am struck that for both there is a personal connection. Susannah and Janam both had fathers who were also young boys, but they were leading entirely different lives in Kolkata. They’ve both died now. Susannah at least has photographs.

For Janam, there were no pictures of his father as a child. So what I knew was from his nightmares and the few stories he told me about his childhood in a colonized war zone.

I have a hard time understanding how my father’s very damaged life affects me as a son.

And then he says something I was n’t expecting.

The colonial police force also employed my grandfather. Therefore, my grandfather participated in many aspects of the colonial system. So our understanding motivations and behaviors are interestingly similar.

There is no memorial or even plaque dedicated to the victims of the Bengal famine anywhere in the world, and at least three million people died there.

Susannah can at least point to a memorial to her grandfather.

He is honoured by a plaque in the church where we worship. ” She explains it’s in the absence of a grave. She’s not sure where his remains are, perhaps in Kolkata.

Honour is a word that Susannah used to describe her grandfather, even though she acknowledges his failures.

” I still find it difficult to picture John Herbert acting in any way dishonourably,” I said,” despite the relatively easy acceptance that history is much more complicated than what we were originally told.

Janam takes a different view”. These kinds of questions of intention have never been topics that have bothered me. Because I believe intentions can always conceal what transpires, I’m much more interested in the historical course of events.

Eighty years on this is still complicated, and raw. I wonder if months into her research, Susannah still feels” shame “is the right emotion to describe how she feels?

She claims to have changed her mind. I believe that shame oversimplifies my feelings. It’s not just about me and what I think.

” It’s part of a greater project, I suppose, of understanding and transmitting understanding of how we got to where we are. We? I mean Britain, I mean, this country”.

Janam agrees that” as a descendant of a colonial official, I do n’t think there is any particular shame that accrues intergenerationally. I think it’s Britain’s shame.

In Bengal, people died from starvation. So, in my opinion, there is room for historical reflection both on the individual and collective levels.

Susannah is reflecting on her legacy. She wants to share her findings with her wider family, and she’s not sure how they’ll receive it.

She hopes that her children will assist her in sorting through the swarms of documents in the Welsh family archive.

As Britain tries to understand what to do with its challenging history and colonial past, they are also grappling with a complex personal legacy.