The earliest pictures capturing the art and beauty of Indian monuments

DAG

DAGA new show in the Indian capital Delhi showcases a rich collection of early photographs of monuments in the country.

The photographs from the 1850s and 1860s capture a period of experimentation when new technology met uncharted territory.

British India was the first country outside Europe to establish professional photographic studios, and many of these early photographers were celebrated internationally. (Photography was launched in 1839.)

They blended and transformed pictorial conventions, introduced new artistic traditions, and shaped the visual tastes of diverse audiences, ranging from scholars to tourists.

While the works of leading British photographers often reflect a colonial perspective, those by their Indian contemporaries reveal overlooked interactions with this narrative.

The pictures at the show called Histories in the Making have been gathered from the archives of DAG, a leading art firm. They highlight photography’s crucial role in shaping an understanding of India’s history.

They also contributed to the development of field sciences, fostered networks of knowledge, and connected the histories of politics, fieldwork, and academic disciplines like archaeology.

“These images capture a moment in history when the British Empire was consolidating its power in India, and the documentation of the subcontinent’s monuments served both as a means of asserting control and as a way to showcase the empire’s achievements to audiences back in Europe,” says Ashish Anand, CEO of DAG.

dag

dagThis is a a picture of Caves of Elephanta taken by William Johnson and William Henderson.

The Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site, are a group of temples primarily dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva in the state of Maharashtra.

William Johnson began his photographic career in Bombay (now Mumbai) around 1852, initially working as a daguerreotypist – the daguerreotype was an early photographic process that produced a single image on a metal plate.

In the mid-1850s, Johnson partnered with William Henderson, a commercial studio owner in Bombay, to establish the firm Johnson & Henderson.

Together, they produced The Indian Amateur’s Photographic Album, a monthly series published from 1856 to 1858.

dag

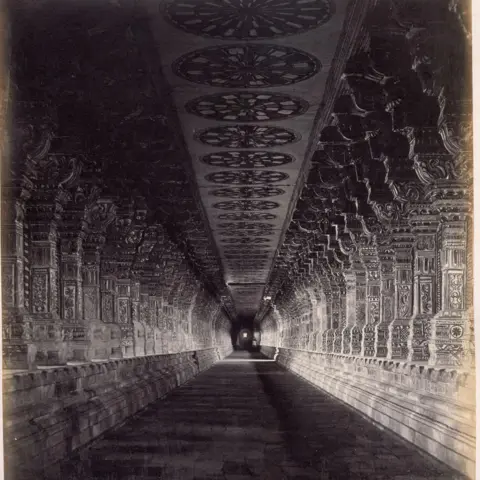

dagLinnaeus Tripe arrived in India in 1839 at the age of 17, joining the Madras regiment of the East India Company.

He began practicing photography and in December 1854, captured images in the towns of Halebidu, Belur, and Shravanabelagola.

Sixty-eight of these photographs, primarily of temples, were exhibited in 1855 at an exhibition in Madras (now a major city called Chennai), earning him a first-class medal for the “best series of photographic views on paper”.

In 1857, Tripe became the photographer for the Madras Presidency – a former province of British India – and photographed sites at Srirangam, Tiruchirapalli, Madurai, Pudukkottai, and Thanjavur.

Over 50 of these photographs were displayed at the Photographic Society of Madras exhibition the following year, where they were widely praised as the best exhibits.

dag

dagJohn Murray, a surgeon in the Bengal Indian Medical Service, began photographing in India in the late 1840s.

Appointed civil surgeon in the city of Agra in 1848, he spent the next 20 years producing a series of studies on Mughal architecture in Agra and the neighbouring cities of Sikandra, and Delhi.

In 1864, he created a comprehensive set of pictures documenting the iconic Taj Mahal.

Throughout his career, Murray used paper negatives and the calotype process – a technique of creating “positive” prints from one negative – to produce his images.

dag

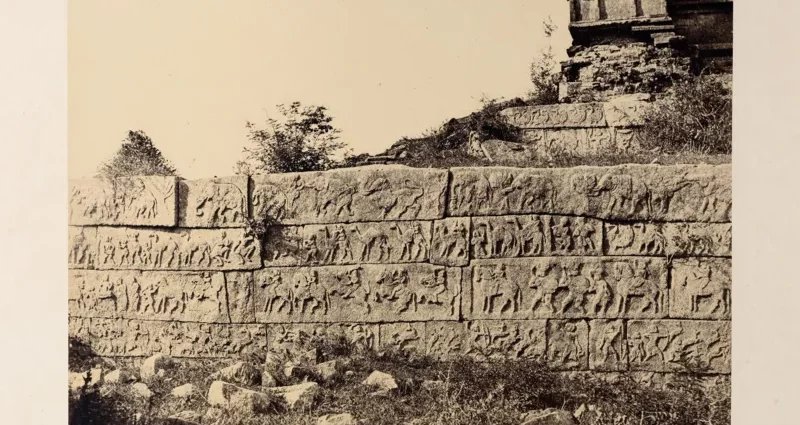

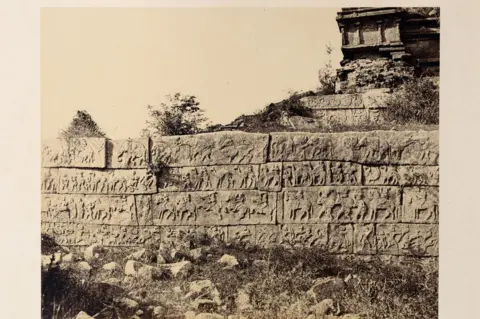

dagThomas Biggs arrived in India in 1842 and joined the Bombay Artillery as a captain in the British East India Company.

He soon took up photography and became a founding member of the Photographic Society of Bombay in 1854.

After exhibiting his work at the Society’s first exhibition in January 1855, he was appointed as the government photographer for the Bombay Presidency, tasked with documenting architectural and archaeological sites.

He photographed Bijapur, Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal, Dharwad, and Mysore before being recalled to military service in December 1855.

Biggs experimented with the calotype process, producing “positive” prints from one negative.

dag

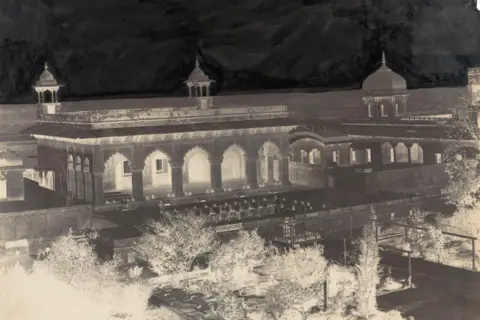

dagFelice Beato, one of the most renowned war and travel photographers of the 19th Century, arrived in India in 1858 to document the aftermath of the 1857 mutiny.

Indian soldiers, known as sepoys, had set off a rebellion against the British rule, often referred to as the first war of independence.

Although the mutiny was nearly over when Beato arrived, he photographed its aftermath with a focus on capturing the immediacy of events.

He extensively documented cities deeply affected by the uprising, including Lucknow, Delhi, and Kanpur, with notable images of Sikandar Bagh, Kashmiri Gate, and the barracks of Kanpur. His chilling photograph of the hanging of sepoys, stands out for its stark depiction.

As a commercial photographer, Beato aimed to sell his work widely, spending over two years in India photographing iconic sites. In 1860, Beato left India for China to photograph the Second Opium War.

dag

dagAndrew Neill, a Scottish doctor in the Indian Medical Service in Madras, was also a photographer who documented ancient monuments for the Bombay Presidency.

His calotypes were featured in the 1855 exhibition of the Photographic Society of Madras and in March 1857, and 20 of his architectural views of Mysore and Bellary were shown by the Photographic Society of Bengal.

Neill also documented Lucknow after the 1857 revolt.

dag

dagEdmund Lyon, who served in the British Army from 1845 to 1854 and briefly as governor of Dublin District Military Prison, arrived in India in 1865 and established a photographic studio in the southern city of Ooty.

Working as a commercial photographer until 1869, Lyon gained significant recognition, particularly for his photographs of the Nilgiris mountain range, which were showcased at the 1867 Paris Exposition.

Accompanied by his wife, Anne Grace, Lyon also captured southern India’s archaeological sites and architectural antiquities.

His work resulted in a remarkable collection of 300 photographs documenting sites in Trichinopoly, Madurai, Tanjore, Halebid, Bellary, and Vijayanagara

dag

dagSamuel Bourne’s stunning images of India, especially from his Himalayan expeditions between 1863 and 1866, stand among the finest examples of 19th-Century travel photography. A former bank clerk, Bourne left his job in 1857 to pursue photography full-time.

Arriving in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1863, he soon moved to Shimla, where he partnered with William Howard to establish the Howard & Bourne studio.

Later that year, Charles Shepherd joined them, forming ‘Howard, Bourne & Shepherd’. When Howard left, the studio became ‘Bourne & Shepherd,’ a name that would become iconic.

Bourne embarked on three major Himalayan expeditions, covering vast regions including Kashmir and the challenging terrain of Spiti. His 1866 photographs of the Manirung Pass, at over 18,600ft (5,669m), gained international acclaim.

In 1870, Bourne returned to England, selling his shares, though Bourne & Shepherd continued to operate in Calcutta and Simla. The studio, which later documented the spectacular Delhi Durbar – the ‘Court of India’ of 1911, an event that saw 20,000 soldiers marching or riding past the silk-robed Emperor and Empress – had a remarkable 176-year legacy before closing in 2016.