‘Europe Last’: How von der Leyen’s China policy traps the EU – Asia Times

Donald Trump’s returning to the White House has exposed Europe’s proper paralysis in impressive fashion. For all their lauded vision, replete with disaster programs, location papers and closed-door sessions entertainment out a second Trump administration, EU leaders find themselves now exactly where they were four years ago: ready and knocked out.

More than two months after Trump’s success, Brussels’ response has been limited to clear reassurances, dismissing his proposals as bare hypotheticals, including his very severe claims to Greenland, which threaten a member state’s regional integrity. Instead of taking important action, the EU has resorted to political hand-wringing and repurposed platitudes about atlantic unification.

However, Europe’s right-wing officials have planted their colors in the Oval Office; Italy ’s Giorgia Meloni and Hungary’s Viktor Orban have now secured their bright cards, while the EU’s conventional power brokers—Germany and France—remain sidelined. Brussels ’ humiliation was complete when the inauguration invitations went out: the EU’s institutional leadership did n’t even make the B-list.

This cracking of Western unity may not appear at a worse instant. Europe faces a delicate balancing act between its Chinese economic pursuits and American protection relationships. Some states are now positioning themselves closer to Trump, eyeing security from taxes, while others remain tied to Chinese markets, their industries greatly intertwined with Beijing’s business.

In this scenario, Ursula von der Leyen’s European Commission is stubbornly sticking to its hawkish stance on China, unaware of the mounting repercussions. All the while, Washington and Beijing could be moving toward their own détente. Trump, ever the dealmaker, might forge an early accommodation with Chinese Xi Jinping—leaving Europe isolated in a confrontation that neither America nor China desires.

In what may become a case study in diplomatic self-sabotage, Brussels has maneuvered itself into a geopolitical dead end, trapped between two colliding giants with neither the tools nor the unity to protect its interests.

The Commission has doubled down on this misguided path, firing off China-focused measures—de-risking policies, economic security frameworks, trade investigations and relentless critiques of China ’s political system—with the fervor of a convert at a revival.

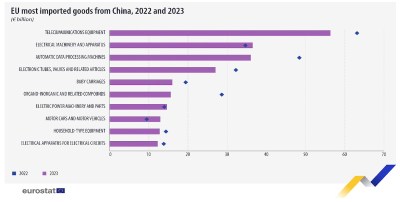

Meanwhile, European industry depends increasingly on Chinese capital goods. According to Eurostat, “ When it comes to the most imported products from China, Telecommunications equipment was the first, although it went down from €63. 1 billion ( US$ 65. 6 billion ) in 2022 to €56. 3 billion in 2023. Electrical machinery and apparatus ( €36. 5 billion ) and automatic data processing machines ( €36 billion ) were the second and third most imported goods respectively. ”

Autos and other consumer goods comprise a small portion of EU imports from China and the political attention given to the automotive sector is in inverse proportion to its economic weight. Paradoxically, after years of American lobbying with European governments to exclude Chinese telecom infrastructure, it has become Europe’s single largest import from China.

Europe-China trade rose modestly in 2024. The Chinese state-run website Global Times reported on January 13, “China’s exports to the EU totaled 3,675. 1 billion yuan, a year-on-year growth of 4. 3 percent, reflecting strong European demand for Chinese goods. Imports from the EU reached 1,916. 4 billion yuan, which is down 3. 3 percent decrease from a year earlier. ”

European industry is already fully integrated into China ’s supply chains. The European Commission ’s talk about “de-risking ” belies the economic reality. Decoupling Europe from China would be like separating conjoined twins with a meat cleaver.

Despite securing her position with just 54 % support, Von der Leyen has cast China as Europe’s strategic nemesis, mirroring Washington ’s stance while disregarding the economic realities facing European businesses and undermining the continent’s geopolitical interests.

This predicament is the result of mistaking submission for strategy. Under Joe Biden, Brussels eagerly auditioned for the role of America’s most compliant ally, parroting tough talk on Beijing while neglecting to build real strategic autonomy.

The real problem is not merely following Biden—it’s the delusion that his policies should endure beyond his tenure. Under MAGA 2. 0, Europe clings to a plan that ’s bound to backfire. The 47th president is not exactly extending an olive branch to Europe, yet, inexplicably, its leaders have operated pretending otherwise.

Now, as Trump’s “America First ” doctrine roars back to life, Europe is about to learn a costly lesson: In the world of great power politics, there are no points for loyalty, only consequences for naivete.

China: Partly Malign, Security Threat, Systemic Threat

In 2024, a year when China and Europe’s institutional leadership failed to meet even once, the US-EU operation to escalate tensions with Beijing appeared meticulously choreographed.

This combative stance found its perfect expression in October, when Europe’s High Representative, Kaja Kallas, took EU diplomacy to new self-destructive heights by inventing a new category, labeling China as “partly malign”—whatever that means.

It was n’t a slip of the tongue but rather a carefully crafted written response that manages to be both inflammatory and meaningless. The same statement anointed Washington as the EU’s “most consequential partner and ally ” while ignoring the looming shadow of Trump 2. 0.

Leading EU-US-aligned think tanks proposed adding a “fourth category ” to the tripartite framework—partner, competitor, systemic rival—labeling China a “security threat ” for its alleged “support ” for Russia in Ukraine, despite Beijing’s refusal to supply lethal weapons. The move prioritized US demands over European interests, reducing complex geopolitics to simplistic binaries while villainizing China without fitting evidence.

In September, a China hawk misquoted von der Leyen to claim she viewed China as a “systemic threat ” requiring “closer transatlantic cooperation. ” Facts did n’t matter—it fit the mainstream narrative.

This rhetoric from prominent leaders and influential advisors signals a hardening stance that heightens tensions without providing viable paths for engagement or resolution. It’s a posture fit for a true military and political superpower—something Europe, under its current leadership, is far from being or achieving.

Let’s be clear about what’s really at stake. Europe’s legitimate grievances with China—the massive trade imbalance, market access restrictions, excessive dependencies, asymmetric competition with Chinese state-owned enterprises—have been buried under an avalanche of ideological posturing. Instead of addressing these concrete issues through pragmatic negotiation, Brussels opted for hostility, torching bridges that took decades to build.

By hitching its wagon to Washington ’s confrontational approach, the bloc forgot a fundamental rule of geopolitics—when two elephants clash, the grass agonizes. And in this case, Europe has enthusiastically volunteered to be the grass.

Today, the EU’s “China abandoned agenda ” collides with the “Trump factor, ” exposing a glaring tactical misstep. Trump’s first term made it crystal clear: he views the EU as an economic rival, not an ally. “The EU is possibly as bad as China, just smaller. It is terrible what they do to us, ” Trump said this week after his inauguration.

And Brussels has resolutely behaved as if this reality could be ignored. Regrettably, five years after the self-proclaimed “Geopolitical Commission ” vowed to restore Europe’s faded glory, the continent is more irrelevant than ever. Washington and Beijing dominate the global stage, while Brussels —stripped of strategy —has played the role of America’s most enthusiastic cheerleader.

The consequences of this negligence are already unfolding. Firstly, Europe has exposed itself to economic and trading pressure from both sides while gaining nothing in return, with limited leverage to negotiate favorable terms with either power.

Moreover, its blind alignment with Biden’s agenda has gutted its ability to forge an independent foreign policy—a reliance that becomes more problematic as Trump’s policies diverge sharply from European interests.

Most critically, by choosing sides in the US-China rivalry rather than maintaining strategic ambiguity, the EU has sacrificed its potential role as a political bridge-builder.

The supreme irony? When Trump starts slapping tariffs on European goods —and he will—Brussels will come crawling back to the East for relief. China, ever the pragmatist, stands ready to rescue Europe from irrelevance—certainly not out of altruism, but calculated realpolitik.

The 50th anniversary of the EU-China diplomatic association in 2025 offered a perfect opportunity for a pivot. Beijing signaled its openness to reset relations. Instead, Von der Leyen swept it under the rug, as if ignoring it might make it irrelevant. It took Xi’s call with European Council President António Costa to remind everyone that this diplomatic milestone even existed.

Brussels, therefore, faces a stark choice: continue its march toward geopolitical irrelevance or chart an independent course. The EU must confront reality. In the great power game, there are no permanent allies, only permanent interests. Until Brussels grasps this fundamental truth, it will continue to play checkers while Beijing and Washington play chess.

All in all, if Europe envisions itself as more than a collection of states, it must adopt the tenacity of a “Europe First ” strategy. It is not about rivalry or mimicry; it ’s about evolution. Trump’s “America First ” was about unapologetic leverage. When it comes to angling for America’s vantage, Trump negotiates hard with friend and foe alike.

Likewise, from dependency to agency, Europe should frame itself as a balancing force: neither submissive nor aggressive, but a power that asserts its autonomy and compels respect from both allies and adversaries.

Sebastian Contin Trillo-Figueroa is a Hong Kong-based geopolitics strategist with a focus on Europe-Asia relations.