Modi’s developed nation dream has no basis in reality – Asia Times

By 2047, the centennial of its independence from the British Raj, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is artistically working to make his nation a designed nation. By predicting that the nation will have the world’s largest economy by the late 20th century, think tank, education, and internet have chimed in.

These conjectures, however, fight a lot with American surface realities. An American political debate revealed these contradictions on February 3, 2025. Rahul Gandhi, the leader of the opposition, painted a depressing picture of India’s proper gaps in its drive to transform the high-tech industry.

His speech, delivered during a discussion on the Movement of Thanks for the President’s annual handle to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament in India, exposed widespread contradictions in the American race to compete with China and the West, a race Gandhi claimed is not even on the monitor.

Given that most politicians, bureaucrats, academics, and popular journalists in India frequently believe in the status of the country as a “global head,” or” Vishwa Guru,” they are a profound realization, and perhaps Gandhi’s is the first time this has happened.

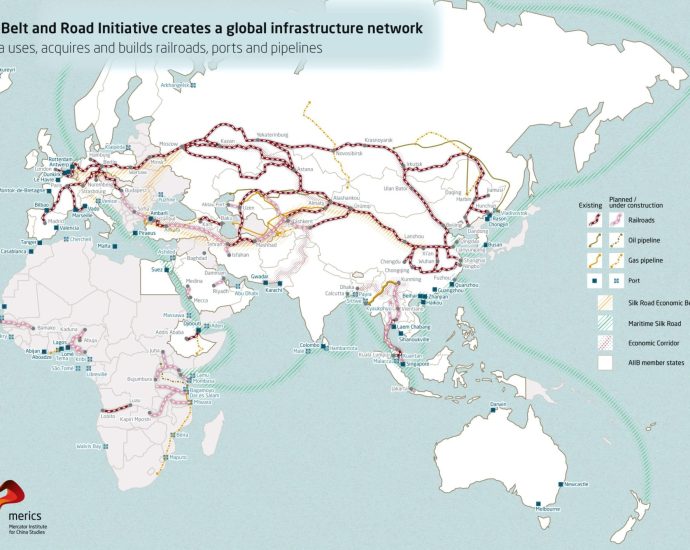

In five crucial places, in my opinion, India is significantly behind China in specific. First, India is laggard behind China in terms of its slow alternative energy transition.

China and Western countries are also in the lead in electric vehicles, clean energy infrastructure, thermal, wind turbines, and hydrogen technology, and are also making substantial advances in developed nuclear technologies like coupled reactors, Helium-3 fusion technology, and liquid salt nuclear reactors. In comparison, India appears to be a passive in all of these industries.

The transition from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles powered by high-storage lithium batteries is a proper market to take the lead role in the world economy in the future, not just a culture change imperative.

Transportation, security, and agriculture are key areas where low-cost, high-efficiency energy-tapping innovations may be required in the future.

However, India lacks a leading position in any of the cutting-edge tech fields that are currently transforming global supply chains and security technologies, such as high-storage lithium batteries, robotics and optics. As a provider of technologies, capital goods, and natural development financing, India’s aspirations run the risk of remaining ambitious despite its continued aspirations.

Next, India’s inability to upgrade its strategic and defense sectors. The Russia-Ukraine issue has demonstrated how inexpensive, efficient aircraft technology powered by electric motors and batteries can surpass traditional, expensive tanks and armored vehicles.

China’s advancements in electronics security systems, including those made by AI-driven drones and energy-efficient surveillance networks, contrast starkly with India’s reliance on archaic platforms and military and strategic technologies, which are more expensive and less effective.

Green technologies and digital warfare capabilities, which India utterly lacks expense and indigenous innovation, may shape the future of high-tech electric warfare. This places China far back in the mix.

Third, in the era of artificial intelligence, India has a terrible large data deficit. Big data production metrics for manufacturing marketing and consumption patterns for business development to address consumers ‘ tastes, preferences, and choices, as the customer is ruler after all, determine AI’s revolutionary possible.

China dominates world manufacturing data on the one hand because it is the world’s stock, and on the other hand, the United States controls intake statistics through big tech like Amazon, Google, X, and Meta. India, in contrast, neither has generation nor use data. India does not possess any of the software platforms it owns.

While India’s manufacturing industry is still a jerrybuilt of Taiwanese components, including export to third countries, especially the US, is still a jerrybuilt. On both the demand side ( consumption ) and the supply side ( production ), India’s digital economy is subject to foreign algorithms.

India is unable to compete in robotics, autonomous systems, and intelligent logistics management as a result of this dual dependency, which stifles domestic AI advancement. India will continue to be a participant in the AI revolution without regaining control over major data. The continued AI conflict between the US and China highlights India’s function as a witness in this field as well.

Third, as a result of its crumbling educational program, India is lagging behind China in high-tech production. While China and the West have changed higher education to give a higher priority to STEM research and innovation, India’s institutions still suffer from underfunding, administrative gravity, and a mismatch between programs and the needs of the high-tech business.

Issues with inclusion and poor quality are also present in public school education. The end result is a lack of skilled workers who can lead advanced manufacturing, research and development, or reverse engineering.

India’s failure to provide start-ups with access to capital adds to this. The backbone of innovation in electronics, high-tech manufacturing, and AI is small and medium enterprises ( SMEs ), which are skewed toward large conglomerates and large businesses in India’s banking system.

Without cultivating a culture of risk-taking and entrepreneurial spirit, India is unable to create the ecosystem necessary for technological reversals. The success of China’s DeepSeek demonstrates how a low-cost start-up can make a significant breakthrough by creating a supportive and creative environment.

In spite of Modi’s” Make in India” rhetoric, the nation still heavily relies on China’s imports of crucial components, including precision optics and semiconductors. In the event of geopolitical tensions with China, Indian factories are essentially assembly lines for Chinese-made parts, leaving the country vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

It depicts India’s manufacturing capacity at a standstill. To compete with China, India must meet the demand and urgency to develop high-speed lithium batteries, 5G or 6G technology, AI-integrated manufacturing systems, and electric motors.

These technologies are essential for everything from satellite networks to electric vehicles, but India lacks the domestic capacity to develop them as quickly as it will be required to do so in the future.

India cannot close without deliberate, state-backed strategies to encourage innovation and increase production, thanks to China’s decade-long investments in these fields. None of these crucial sectors are currently India’s dominant.

Another sombering ground fact: India’s struggle to become a superpower is a result of its slow economic and technological development. The transition to a high-tech manufacturing economy and, as a result, a strategic influencer on the global stage are not isolated sub-sets but fundamental pillars of India’s rise to a high-tech manufacturing economy and, as a result, a result of the evolution of big data sovereignty, big data sovereignty, STEM education reform, and high-tech manufacturing.

Modi’s vision of a developed India by 2047 depends on closing these gaps, but current policies prioritize rhetoric over substance. The danger is that if India doesn’t develop these five sectors, it could end up being a perpetual” country of the future” —a phrase used by Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew unless it takes action to address its structural flaws with the utmost urgency.

In the interim, the gap between Modi’s goals and India’s actual capabilities will remain a gap.

Bhim Bhurtel is a member of the X network, @BhimBhurtel.