BYD racing away with China’s EV market – Asia Times

BYD overtook Tesla to become the world’s largest supplier of battery-powered electric vehicles in the fourth quarter of 2023, by a substantial margin of 526,000 to 484,000 units sold. But in China, the race for market dominance isn’t nearly as close.

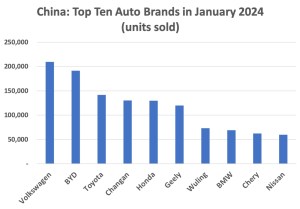

Indeed, Volkswagen, BMW, Toyota, Honda, Nissan and several Chinese companies outpace Tesla in the overall Chinese auto market.

American and European politicians who are fond of ranting about China’s closed markets should take note that Chinese consumers appreciate German and Japanese quality like almost everybody else. They also admire Tesla but are not fanatic about it.

In January 2024, BYD’s share of the Chinese market for battery electric vehicles was 26.2%, according to data from the China Passenger Car Association cited by CarNewsChina. Tesla’s share was 10.6%.

Volkswagen ranked sixth with 4.2%. China’s Wuling, Aion and Changan outranked Volkswagen, while Zeekr, Geely, Nio and Leap rounded out the top ten.

In the Chinese auto market as a whole, Volkswagen was the best-selling brand with a market share of 10.3%. BYD ranked second at 9.4% and Toyota third at 7.0%. Changan slightly outsold Honda, which had 6.4% of the market.

BMW ranked eighth at 3.4% and Nissan tenth at 2.9%. Geely, Wuling and Chery completed the top ten. Tesla’s share was only 2.0%.

Five of the ten best-selling car models in January were foreign, including the Tesla Model Y, which ranked sixth. The Changan CS75 Plus was the most popular, followed by the Volkswagen Lavida, BYD Song Plus, Nissan Sylphy and Aito Wenjie M7.

The BYD Qin Plus and Seagull were also in the Top Ten, as were the Volkswagen Sagitar and Honda CR-V. The list was compiled by CarNewsChina, which cited Chinese auto websites Dongchedi and Yiche.

In 2023, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) accounted for only 5.9% of the Volkswagen Group’s sales in China but that will change. Deliveries were up 72.3% year-on-year in the fourth quarter, following the start of operations at the company’s new EV factory in Hefei.

By 2030, Volkswagen China plans to increase the share of new energy vehicles – including both BEVs and hybrids – in its product mix to 40%. This will put more pressure on Tesla, which doesn’t make hybrids.

BYD makes almost as many hybrids as it does BEVs, so its electric vehicle output is actually about twice that of Tesla’s – not slightly larger as commonly reported. Moreover, BMW’s joint venture with Brilliance China Automotive is expanding EV and battery production in Shenyang.

Toyota, Honda, Nissan and Mazda, which is an affiliate of Toyota, make and sell EVs (mostly hybrids) in China through joint ventures. Toyota works with FAW and GAC, Honda and Nissan with Dongfeng, and Mazda with Changan and FAW.

Last November, it was announced that the new Mazda CX-50 sold in China by Changan Mazda Automobile incorporates the Toyota Hybrid System.

Honda and Nissan also have joint R&D projects with Tsinghua University while engineers from FAW, GAC and BYD participate in projects at Toyota’s Intelligent ElectroMobility R&D Center, which promotes the development of battery-powered, hybrid, plug-in hybrid and fuel cell EVs in China.

The Chinese government wants sales of these New Energy Vehicles, which accounted for 32% of new car sales in China last year, to reach 45% of new car sales by 2027. German and Japanese automakers have said they aim to maintain their market rankings as China advances toward that target.

Follow this writer on X: @ScottFo83517667