When Trump and Xi seek a war-ending trade deal – Asia Times

As Xi Jinping declares his eagerness to meet with Donald Trump’s White House, the chances of a China-US trade agreement are once more rising.

With obvious pre-conditions, of training. According to reports from Bloomberg and other media outlets, President Xi’s federal wants Trump and his cabinet to tone down the rhetoric, define what precisely Washington wants, and name a certain point person to take the lead of the discussions. On Wednesday, China appointed a new business agent.

Each of these could be a non-starter – or a teaser over time– given US Trump’s predilection for late-night social-media fits and exotic plan shifts from moment to moment. After all, Trump’s taxes on imported goods have increased from 10 % to 145 % at warp speed.

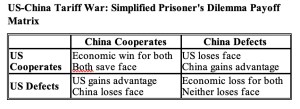

The real issue is not whether Xi and Trump reach a Group of Two industry agreement, though. It’s whether it will amount to anything other than a face-saving practice of rearranging the deckchairs on a sinking business, economic and financial marriage.

Japan can provide some information from its powerful encounter with the Trump 1.0 crew in this regard. Effective because Shinzo Abe, then-Prime Minister, made sure Japan’s bilateral trade negotiations with Trump World were unbroken.

Case in point: Trump was so frightened for a “win” versus America’s long-time rival that he agreed to leave auto industry agreements for another day. Of course, Shigeru Ishiba, the current leader of Japan, was left to face Trump 2.0 in the wake of the scrub of a free-trade agreement.

Trump’s industry representatives and US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent are now negotiating with Ishiba’s business negotiators, under the direction of Japan’s minister of economic revitalization Ryosei Akazawa.

Immediately, Trump claimed there’s been “big development”. Tokyo may be able to escape once more with a watered-down, face-saving business agreement that doesn’t lose even half as much as Trump may claim, given the chaos caused by Trump’s tariffs and the multi-trillion-dollar decline in US stocks.

However, Xi is aware that China has a little stronger side.

This weekend’s news that gross domestic product exceeded expectations to develop 5.4 % year on year in the first third suggests China is moving into the Trump 2.0 tax neighborhood with good speed. No bursting at all, but not as much as some economists had predicted.

Xi also put on quite a show by retaliating against Trump’s string of tariffs, even increasing China’s levy on US goods to 125 %. In the process, China communicated it’s set to support considerable financial problems before caving to Trump’s needs. And that Team Xi anticipates that Trump’s team will bring their own sugar and agreements.

By calling Trump’s hill, Xi made it clear that he had taken Washington by surprise and forced him to engage in a number of humiliating back-and-forth. It’s fair to ask which market is not getting a carve-out on Trump’s sky-high transfer taxes on Chinese products?

Some policy wonks who are suffering from PTSD from Trump 1.0 are talking about subsidies for farmers in response to China’s punitive taxes on their products. All of this suggests a lack of commitment rather than a high level of suffering.

Today, even the Federal Reserve is calling Trump’s mountain. Fed Chair Jerome Powell threw cold waters on Trump’s reassurance that lower US prices may lessen the harm caused by taxes in a statement on Wednesday.

These are “very important policy changes,” according to Powell. ” There isn’t a present knowledge of how to think about this”.

The issue, according to Powell, is that” the level of the price rises announced so far is substantially higher than anticipated” and that doubt about the potential impact on the economy. That includes family desire and prices falling.

” Jerome Powell only laid down the law with Trump”, says David Russell, world mind of business plan at TradeStation. It was both a distinct warning about recessions and a charter that the Fed won’t allow the White House to implement price reductions.

The Fed faces a rapidly growing problem because of the risk that the US is entering a large inflation-flatflatlining growth period.

As Austan Goolsbee, leader of the Chicago Fed, puts it,” a price is like a bad supply shock. That is a stagflationary impact, which means that it simultaneously worsens both sides of the Fed’s two authority. There is not a common handbook for how the central banks should listen to a stagflationary shock because prices are rising while jobs are lost and progress is slowing.

Cleveland Fed President Beth Hammock adds that” this is a hard set of challenges for economic policy to understand. There is a strong argument to keep monetary policy low in order to stabilize the risks from more inflated prices and a slowing labour market, given the economy’s starting point and with both sides of our mandate expected to be under pressure.

We would consider how far the economy is from each goal, and the potentially various time horizons over which those respective gaps would be anticipated to close, according to Powell, when he said if stagflation became a reality.

This nascent Trump-Fed standoff weakens the White House’s hand heading into China trade talks.

The Trump White House is already being chastised by international investors who are already reliant on US government debt. Credit rating organizations are concerned about the prospect of 10-year yields approaching 4.5 %, as well as Asian central banks, who own US$$ 3 trillion in US Treasuries.

The last time the US bond market flashed such warning signals was March 2020, just as the pandemic was taking hold.  ,

Fortunately, according to Brookings Institution economist Nellie Liang, the Fed’s purchases made at the time to restore market functioning were in line with its monetary policy goals of the time: to stimulate the economy and lower inflation to its target of 2 %.

” It’s possible, however, that the Fed may someday confront the need to purchase Treasury securities at a time when doing so would conflict with achieving its mandate of maximum employment and price stability”, Liang says. The absence of this conflict highlights the value of regulatory changes to improve Treasury market resilience.

The chances of such upgrades are close to zero because US Congress is essentially gridlocked by partisan sniping.

In the meantime, bond vigilantes are letting Trump know that his tariffs are a clear and present danger to US financial stability. And Xi doesn’t like how the US stock market is affecting Trump’s approval ratings with voters, which is a problem Xi doesn’t have.

Advantage Xi’s far more rigid system also makes China less vulnerable to a significant capital flight as investors try to cast their ballots with their feet.

” If doubts about the exceptional status of the dollar were to increase, this would be very credit negative for the US”, says Alvise Lennkh-Yunus, head of sovereign ratings at Berlin-based Scope Ratings.

Unsurprisingly, China’s two leading figures are taking China’s charm offensive on the road. Xi is based in Southeast Asia, which is now his main trading partner.

In Hanoi, Xi and Vietnam’s Communist Party Secretary-General To Lam agreed to” jointly oppose unilateral bullying” amid trade jousting. Trump’s” Liberation Day” announcement on April 2 sent a 46 % tariff to Vietnam.

According to Xinhua’s official news release, Xi stated that” we must strengthen strategic resolve and uphold the stability of the global free trade system as well as industrial and supply chains.”

Stephen Olson, a former US trade negotiator, told the BBC that Xi’s comments were” a very shrewd tactical move. Trump appears determined to annihilate the trade system, but Xi portrays China as the proponent of rules-based trade and portrays the US as a “reckless rogue nation.”

An” Asian family” that can exploit regional cohesion for greater stability and unity was pushed by Xi in Phnom Penh. Written between the lines in bold font was Trump’s divide-and-conquer strategy targeting economies from the biggest industrialized ones to those in the Global South.

Premier Li Qiang has been managing the phones in China’s second-largest market, Europe. According to the EU side, Li and Ursula von der Leyen discussed China’s crucial role in preventing potential trade diversion caused by tariffs, particularly in those sectors that are already in danger of overcapacity.

Chief executive of Eurizon SLJ, Stephen Jen, an economist, advises against taking China’s economic diplomacy efforts for granted. According to Jen, economies that weren’t aligned with either the US or the Soviet Union’s orbit accounted for only 18 % of global output and 14 % of global trade during the Cold War era.

Nowadays, such third parties, including the EU, play a “much heftier” role — 44 % of global output and 64 % of trade. According to Jen,” Europe holds the key to the ultimate outcome of this US-China rivalry.”

China exported almost the same amount of goods to the EU in 2024, or$ 516 billion, which is almost the same as what it did to the US. Though China ships more to the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations ( ASEAN ) economies, it’s “realistic” to assume that one-third of shipments bound for the US get redirected.

” This process could cascade to effectively lead to the ‘non-aligned’ countries taking the US’ side, leaving China economically isolated,” Jen explains.

Trump 2.0, who may not be aware of these dynamics, can’t seem to impose tariffs on Europe quickly enough. Hence, the outreach efforts by Xi and Li.

Trump, however, may be targeting both friends and foes with direct tariffs and additional taxes on steel, aluminum, and cars in order to advance China’s interests. By some standards, China needs a deal with Trump at the very least to lessen uncertainty.  ,

The effective tariff increase from 11 % in 2024 to 14 % in 2024 will shake up trade dynamics in previously unthinkable ways, according to Hui Shan, chief China economist at Goldman Sachs. Particularly when considering that exports to the US support between 10 million and 20 million Chinese factory jobs.

Demand from ASEAN may be growing, but not fast enough to offset lost American business. Shanghai’s famously busy ports are becoming quiet as idle US-bound tankers crowded the city’s shorelines, according to Caixin.

Despite this, Xi’s China has made it abundantly clear that this will be real negotiations, not the one Trump envisioned.

This could quickly blow up the talks or enable China to get away with its own Japan-like trade deal “light” win. In any case, China may have more cards in this make-a-deal situation than Trump might realize.

Follow William Pesek on X at @WilliamPesek