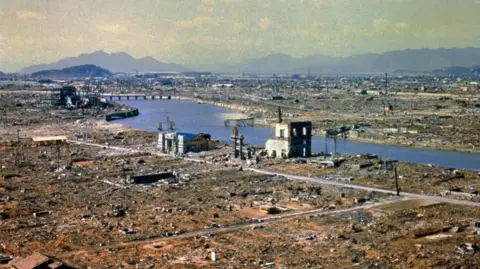

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was early in the day, but currently hot. Chieko Kiriake searched for some tone as she wiped the sweat out of her face. As she did but, there was a bright mild- it was like everything the 15-year-old had previously experienced. It was 08: 15 on 6 August 1945.

” It felt like the moon had fallen- and I grew dizzy”, she recalls.

The United States had merely dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Chieko’s hometown, marking the first time a atomic weapons had ever been used in combat. Military forces fighting in World War Two were still at war with Japan despite Germany’s surrender in Europe.

Warning: This article contains visual content that some readers may find threatening

Chieko was a scholar, but like many older children, had been sent out to work in the factories during the conflict. She stumblingd to her class while carrying a stricken companion. Many of the kids had been severely burned. She rubbed ancient fuel, found in the home economics school, onto their wounds.

” That was the only course of action we had use,” she said. They died one after the subsequent”, says Chieko.

I buried my colleagues with my own hands after our teachers told our older students who were still alive to drill a hole in the park. I felt but terrible for them”.

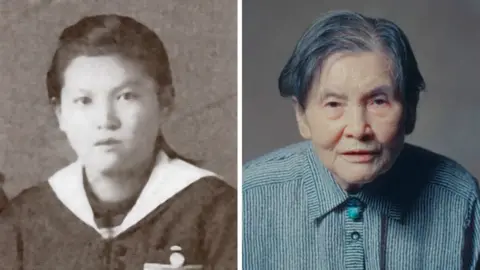

Chieko is presently 94 years older. Time is running out for the surviving subjects, known as hibakusha in Japan, to tell their stories after nearly 80 years since the nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Due to the nuclear attack, several people have experienced discrimination, lost loved ones, and lived with health issues. They are currently releasing their experience for a BBC Two movie that will document the history so that it serves as a reminder for the future.

BBC/Minnow Films/Chieko Kiriake

BBC/Minnow Films/Chieko KiriakeAfter the pain, fresh life started to return to her town, says Chieko.

” People said the grass would n’t grow for 75 years”, she says,” but by the spring of the next year, the sparrows returned”.

Chieko claims she has been close to death numerous instances throughout her life, but that something extraordinary has allowed her to survive.

At the time of the attacks, babies made up the majority of the hibakusha alive today. As the hibakusha- which translates absolutely as “bomb-affected-people”- possess grown older, worldwide issues have intensified. The threat of a radioactive increase seems more real to them than ever.

When she considers issues happening today, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza conflict, 86-year-old Michiko Kodama says,” My body trembles and weeping overflow.”

” We must never let the nuclear bombing’s pit to become rebuilt.” I feel a sense of issue”.

Michiko, who claims to speak out in support of nuclear peace, claims to do so to pass on the experiences of those who have passed down to the next generation.

” I think it is important to learn first-hand accounts of hibakusha who experienced the strong bombing”, she says.

BBC/Minnow Films

BBC/Minnow FilmsWhen the weapon dropped on Hiroshima, Michiko was seven years old and attending college.

” Through my classroom’s windows, there was a flash of severe light coming our way. It was bright, orange, magic”.

She describes how the dirt that was sprayed all over the classroom, including the windows, table, and chairs, splintered and shattered.

” The sky came crashing down. So I hid my brain underneath the desk.

After the fire, Michiko looked around the heartbroken area. In every way, she was see trapped hands and legs.

” My companions were saying,” Assist me, please, and I crawled from the class to the hall.”

When her parents arrived to pick her up, he carried her on his returning home.

Black weather, “like mud”, fell from the sky, says Michiko. It was a mixture of nuclear components and leftovers from the explosion.

BBC/Minnow Films/Michiko Kodama

BBC/Minnow Films/Michiko KodamaShe has never been able to forget the drive house.

” It was a scene from hell”, says Michiko. The persons who were escaping toward us had entirely lost their clothing and their bodies.

She recalls seeing one woman who was about the same age as her, all alone. She was terribly melted.

” But her eyes were wide open”, says Michiko. ” That woman’s vision, they pierce me still. I ca n’t forget her. Yet though 78 years have passed, she is seared into my head and soul”.

If her relatives had stayed in their previous house, Michiko would not be alive today. It was only 350m ( 0.21 miles ) from the spot where the bomb exploded. About 20 weeks before, her family had moved apartment, just a few miles apart- but that saved her life.

Estimates put the number of lost life in Hiroshima, by the end of 1945, at about 140, 000.

In Nagasaki, which was bombed by the US three days later, at least 74, 000 were killed.

Sueichi Kido lived just 2km ( 1.24 miles ) from the epicentre of the Nagasaki blast. He was five years old when he was burned to the side of his face. His mother, who received more severe injury, had protected him from the total effect of the storm.

Sueichi, who is now 83 and has recently traveled to New York to speak at the UN to raise awareness of the risks of nuclear weaponry, declares,” We hibakusha have not given up on our quest to stop the development of any further hibakusha.”

The first thing he recalls seeing when he woke up after falling asleep from the blast’s impact was a dark oil can. He had been mistaken for an oil could for years as the source of the explosion and the nearby destruction.

His parents chose to protect him from the reality that it had been a nuclear attack, but they would cry whenever he mentioned it.

BBC/Minnow Films

BBC/Minnow FilmsNot all wounds were immediately visible. In both towns, many people in the weeks and months following the fire started to exhibit signs of energy poison, and cancer and cancer were on the rise.

For years, individuals have faced discrimination in culture, particularly when it came to finding a mate.

” ‘ We do not like hibakusha blood to enter our community collection,’ I was told”, says Michiko.

But afterward, she did married and had two kids.

She lost her mother, father and brothers to cancers. Her child passed away in 2011 from the illness.

” I feel depressed, angry and afraid, and I wonder if it may be my change future”, she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnother weapon veteran, Kiyomi Iguro, was 19 when the weapon struck Nagasaki. She describes having a miscarriage and marrying into a distant relative’s home, which her mother-in-law attributed to the nuclear bomb.

” ‘ Your prospect is frightening.’ That’s what she told me”.

Kiyomi claims that she was given the directive to keep quiet about telling her neighbors that she had experienced the nuclear weapon.

BBC/Minnow Films/Kiyomi Iguro

BBC/Minnow Films/Kiyomi IguroSince being interviewed for the video, Kiyomi has unfortunately died.

However, she would n’t go to Nagasaki until she was 98 and ring the bell at 11: 02, the time the bomb hit the city, to wish for peace.

BBC/Minnow Films

BBC/Minnow FilmsSueichi went on to teach Chinese past at school. Knowing he was a hibakusha cast a shadow on his personality, he says. But then he realized that he was n’t a typical person and had a responsibility to speak out to save humanity.

” A feeling that I was a unique individual was born in me”, says Sueichi.

The hibakusha all feel the same way about making sure the past does n’t turn into the present.

Atomic People will be broadcast on Wednesday 31 July on BBC Two and BBC iPlayer.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this story, support and advice is available via the BBC Action Line.