On a sunny afternoon in Melbourne 30 years ago, Aussie Rules footballer Nicky Winmar defiantly stared down a bitter crowd hurling racist slurs, spit and drink cans at him.

Lifting his shirt, the Aboriginal man pointed at his skin and shouted at them: “I’m black, and I’m proud to be black.”

That Saturday afternoon at Victoria Park would go down in Australian sporting history. Many hoped it would change the Australian Football League (AFL), which had been turning a blind eye to rampant racism.

But fast forward three decades and the league has again found itself at the centre of a racism storm.

In a full circle moment last month, Aboriginal player Jamarra Ugle-Hagan recreated Mr Winmar’s iconic gesture, days after he too was racially vilified by a match spectator and subjected to a torrent of online hate.

The AFL’s efforts to mark the 30th anniversary of Mr Winmar’s stance have also been overshadowed this week after four Indigenous players reported receiving racist comments online.

Such abuse is just the latest in a long list of racism scandals which have plagued the AFL – raising questions about the sport’s culture.

‘I’ve started something’

In 1993, racism was commonplace at Australian sport matches.

But the level of abuse aimed at Mr Winmar and his St Kilda teammate Gilbert McAdam by opposition fans that day was so bad that Mr McAdam’s father left the stadium in tears.

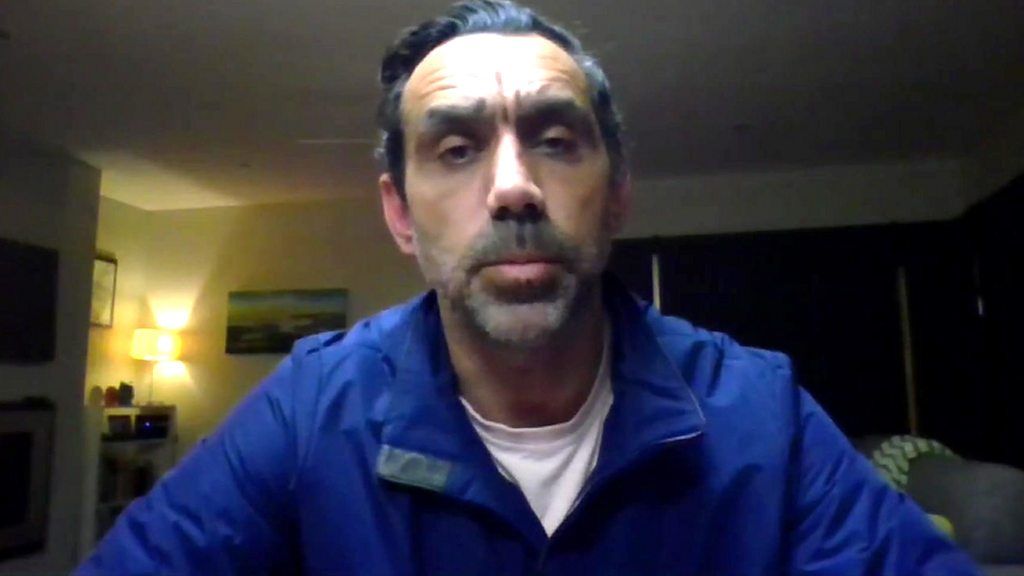

“The abuse and the threats were just horrendous… based on something I couldn’t control, the colour of my skin,” Mr Winmar tells the BBC.

“It was just hurtful… all I wanted to do was just play good footy.”

He says his gesture was a “spontaneous” reaction borne out of frustration, and not something he imagined would blow up.

“[But] the next day someone said did you see the paper, and I said, ‘Oh god, I’ve started something now’.”

Photojournalist Wayne Ludbey knew how significant the moment was the second his lens shutter clicked.

After fighting his all-white newsroom to place the image on the front page of Melbourne’s The Age newspaper, it made waves around Australia.

But he believes at the time the true message of the moment was lost on many.

Many Australians – even Mr Winmar’s own teammates – didn’t understand his reaction, and the player felt his career was at risk if he continued to speak out, Mr Ludbey says.

“There was no support, so much so that Gilbert and Nicky… were told by the club not to bring their personal problems into the club,” he said.

But sports management researcher Lionel Frost says that moment was a “turning point” for culturally diverse players, who were emboldened to speak up about racist abuse from both spectators and their peers.

Within two years the AFL became the first sport in the country to bring in a player’s code of conduct banning racial vilification.

“On the field, I’d be very confident in saying the game has changed because of the code of conduct, and because of what Nicky Winmar did,” Mr Frost says.

But off the field – in clubhouses, spectator stands, and commentary boxes – it appears that too little has changed critics say.

Still ‘nowhere close to safe’

Generations of players continue to suffer abuse.

Contemporary giants of the game have spoken about how a pattern of racism – and the response from the AFL and the media – forced them out of the game.

Adam Goodes, one of the most decorated players in AFL history, called out a racist taunt by a teenage spectator in 2013.

But instead of support, he was criticised by pundits and relentlessly booed by crowds in the years following, including in 2014 when he was Australian of the Year and advocating against racism.

Such treatment left him “heartbroken”, he said. He made an early retirement in 2015.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

AFL legend Eddie Betts – who had a banana thrown at him from the stands in 2016 – has similarly confessed he may not have retired in 2021 if he hadn’t been racially abused on a weekly basis throughout his 17-year career.

The attacks aren’t limited to Indigenous players. In recent seasons, a Muslim player of Lebanese descent was called a “terrorist” by a spectator while African-Australian players have also been singled out for abuse.

The AFL remains “nowhere close” to a safe environment for culturally diverse players, sports historian Matthew Klugman says.

But comments aimed at First Nations players – often with colonial overtones – are particularly intense and hurtful. And they remain frequent.

“It’s very hard to heal when the violence keeps occurring,” Dr Klugman says.

Search for solutions

The AFL is Australia’s richest and best-attended professional league. It has repeatedly said it is working to stamp out racism in the sport.

Gillon McLachlan, head of the league since 2014, has called the recent abuse “abhorrent”.

“This has to stop,” he said this week, admitting he was exasperated. “The set of words I have, I am just sick of saying them.”

But the league’s policy for dealing with offenders is unclear. The AFL has also admitted it has trouble identifying offenders, particularly online.

Based on media reports, a handful have received match bans or had their club membership suspended.

Meanwhile, rival code the National Rugby League has appeared to commit to tougher action. It has said that anyone who racially abuses or threatens players will be reported to police.

But AFL critics say it’s taken a largely tokenistic approach. They have called for harsher punishments – like lifetime bans for those caught – and there are pleas for white players to shoulder the burden in speaking up on the issue.

“Enough’s enough. When are we going to see a stance?” Mr Betts, the former star player, said on Fox Sports this week.

“The strategy just doesn’t seem to be cutting through… it’s just happening year after year,” Mr Ludbey adds.

Many say the culture also needs to be tackled at the club level.

In just the past two years, two of the league’s most successful teams have been accused of racist practices.

A 2021 report into Collingwood club – one of the league’s wealthiest – found a culture of “systemic racism”.

This is the same club whose fans racially abused Mr Winmar that day in 1993 and Mr Goodes again in 2013.

The investigation into Collingwood was triggered after a former player sued in 2020. Héritier Lumumba, who has Brazilian and Congolese-Angolan heritage, said he was nicknamed “chimp” by his teammates and ostracised after reporting racist incidents.

A similar investigation into another club last year – Hawthorn – unearthed allegations Aboriginal players were bullied by senior coaching staff.

The players were reportedly isolated from family, told to leave their partners and one alleges he was ordered to end a pregnancy, claims the senior club officials involved refute.

The revelations sparked broader calls – from the players’ association, even politicians – that a racism inquiry into the whole sport was needed.

“You’ve got these horrific racist spot fires occurring all the time,” Dr Klugman says.

“Some form of independent truth telling, led by Indigenous peoples and not controlled by the league, is essential in terms of creating the possibilities of healing and justice,” he says.

Mr Winmar says the AFL is trying, but it needs to do more. He applauds the leadership of current players like Mr Ugle-Hagan – who is only 21.

But he knows the toll such advocacy takes, and is deeply frustrated that decades on, players are still carrying the same burden.

“What’s going to happen to the next generation? I’ve got grandkids coming through [the sport],” he says.

“I can’t believe that this is still happening.”

Related Topics

-

-

21 September 2022

-

-

-

1 February 2021

-

-

-

22 September 2022

-