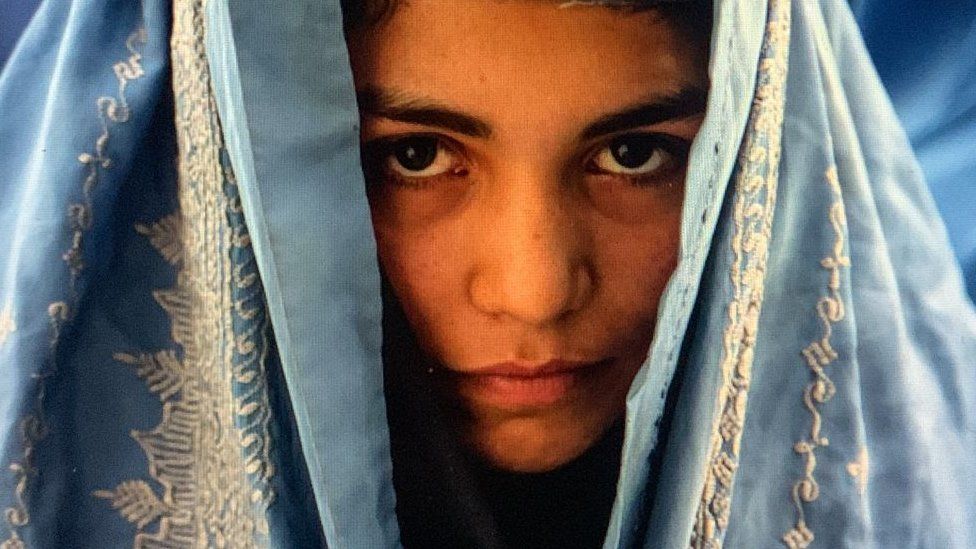

Teenage girls have told the BBC they feel “mentally deceased” as the Taliban’s restrictions on their training prevents them from returning to school after again.

More than 900 times have now passed since women over 12 were initially banned.

The Taliban have consistently promised they would get readmitted after a number of issues were resolved- including ensuring the education was” Islamic”.

But they have made little post as a second new school year started without young girls in school this week.

The BBC has asked the Taliban’s education secretary for an explanation, but he has thus far not responded. The Taliban’s main official told local Television there had been” some problems and deficiencies for different causes” in getting the restrictions lifted.

According to Unicef, the ban has then impacted some 1.4m Afghan ladies- among them, past colleagues Habiba, Mahtab and Tamana, who spoke to the BBC last month.

The promise they described 12 month ago is still there, but seems to have dwindled.

” In reality, when we think, we do n’t live, we are just alive”, Mahtab, 16, says. ” Think of us like a moving dead body in Afghanistan”.

Tamana- who dreams of a PhD- agrees. ” I mean, we are actually alive but intellectually dead”, she says.

Women were initially singled out and prevented from going to secondary school again in September 2021- a fortnight after the Taliban took control of the country.

Acting Deputy Education Minister Abdul Hakim Hemat afterwards told the BBC that women would not be allowed to attend secondary school until a new training plan in line with Islamic and Afghan practices was approved, which would be in time for the start of class in March 2022.

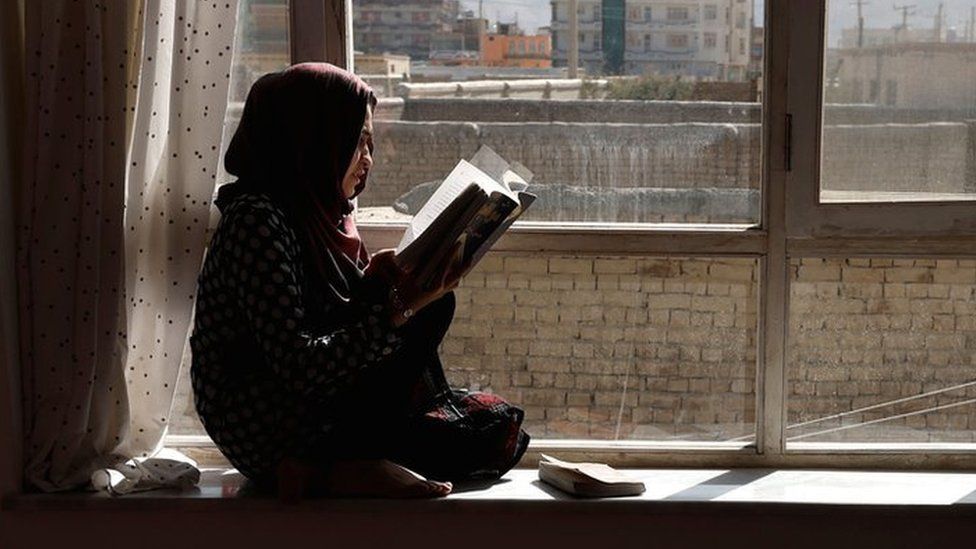

Two years later, Zainab- never her true name- is among the 330, 000 girls Unicef estimates may have started intermediate school this March. She had held onto wish that she and other girls in Grade Six would be able to proceed, up to the point her headmaster entered the exam hall to discuss they may not be able to profit for the fresh term.

Zainab had been top of her class. Then, she tells the BBC:” I feel like I have buried my goals in a dark gap”.

Zainab’s papa has attempted to leave Afghanistan, but so far without victory. Actually, Zainab’s only alternative is classes at government- managed spiritual schools, or madrassas- something the family do not want.

” It is not an option to school”, her father says. ” They will only tell her spiritual content”.

For today, she attends an American course being quietly run in her village- one of many which have slowly emerged in defiance of the ban in the last few years. Girls have also been able to keep up their studies by following courses online, or watching programmes like BBC Dars- an education programme for Afghan children, including girls aged 11- 16 barred from school, described as a “learning lifeline” by the United Nations last year.

Where to find Dars

- BBC News Afghanistan TV and radio satellite channel

- BBC News Pashto and BBC News Dari Facebook and YouTube channels

- BBC Persian TV

- FM, short- wave and medium- wave radio

But Zainab and girls like her are among the more fortunate ones. When families are struggling to get enough to eat- as many in Afghanistan are- accessing online education is simply not seen” as a priority for their daughters”, notes Samira Hamidi, Amnesty International’s regional campaigner.

The future for many of Afghanistan’s girls is “bleak”, she warns- pointing to the fact young girls are continuing to be married off when they reach puberty, and are further endangered by the Taliban’s rollback of laws designed to protect women in abusive marriages.

And it is not just 13- year- olds being prevented from accessing an education. The BBC has found the ban even being extended to younger girls if they appear to have gone through puberty.

Naya, not her real name, is just 11 but is no longer attending school in her home province of Kandahar. Her father says the government has “abandoned” her because she looks older than she is.

” She is larger than average, and that was the reason the government told us she could n’t go to school. She must wear the veil ( hijab ) and stay at home”.

He does n’t hold out much hope for the rules changing under the current regime, but was keen to stress one point: the idea the people of Afghanistan backed the Taliban’s ban was an “absolute lie”.

” It is absolutely an accusation on Afghans and Pashtuns that they do n’t want daughter’s education, but the issue is vice- versa”, he said. ” Specially in Kandahar and other Pashtun provinces ( where Pashtun people live ), a lot people are ready to send their daughters to schools and universities to get education”.

The ban on a secondary education is far from the only change these girls are facing, however. In December 2022, women were told they could no longer attend university. Then there were the rules restricting how far a woman could travel without a male relative, on how they dressed, what jobs they could do, and even a ban on visiting their local parks.

There are hopes, says Amnesty’s Samira Hamidi, that the secret schools and online education” can be expanded”. But, she added:” In a country with over one million girls facing a ban on their fundamental human rights to education, these efforts are not enough”.

What it needs, she argues, is” for immediate and measurable actions by the international community to pressurise the Taliban”, as well as wider international support for education across the country.

But until that happens, girls like Habiba, Mahtab and Tamana will remain at home.

” It’s very difficult”, says Habiba, 18. ” We feel ourselves in a real dungeon”.

But she says she still has hope. Her friend Tamana is not so sure.

” Honestly, I do n’t know whether the schools will reopen or not under this government which does n’t have a bit of thought or understanding for girls”, the 16- year- old says.

” They count the girls as nothing”.

Additional reporting by Mariam Aman and Georgina Pearce

Related Topics

-

-

14 October 2023

-

-

-

28 August 2023

-

-

-

16 August 2023

-

-

-

15 August 2023

-

-

-

1 April 2023

-

-

-

27 March 2023

-

-

-

21 December 2022

-

-

-

8 December 2021

-