BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonWarning: This story contains troubling information from the start.

” This is doomsday for me,” I thought. I feel so many pain. Can you picture what I’ve gone through while watching my kids pass away? says Amina.

She’s lost six kids. One of them is nowadays vying for her career, and none of them has lived past the age of three.

Seven-month-old Bibi Hajira is the size of a kid. Suffering from severe acute nutrition, she occupies half a pillow at a hospital in Jalalabad local hospital in Afghanistan’s northeast Nangarhar state.

” My kids are dying because of hunger. All I can pull them is dried bread, and waters that I heated up by keeping it out under the sun”, Amina says, almost shouting in pain.

Perhaps more damaging is how far her story is from being unique, and how many more lives could be saved by receiving treatment right away.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonBibi Hajira is one of 3.2 million kids with chronic hunger, which is ravaging the country. It’s a problem that has plagued Afghanistan for centuries, which has been brought on by 40 years of war, extreme hunger, and a myriad other elements in the three decades since the Taliban took control.

However, the condition has then sunk to an unprecedented level.

It’s difficult for anyone to think what 3.2 million looks like, so the tales from a small hospital room can provide an insight into the coming disaster.

There are 18 child in seven rooms. It’s never a seasonal boom, this is how it is day after day. The room just experiences a disturbing silence when a pulse rate monitor’s high-pitched beeps break the unsettling silence.

Most of the kids do n’t wear oxygen masks or are sedated. They are alive, but they are far too poor to speak or move.

Sharing the base with Bibi Hajira, wearing a purple tunic, her little finger covering her face, is three-year-old Sana. Her uncle Laila is taking care of her because her mother passed away while giving birth to her sister a few months ago. Laila crosses my shoulder and extends seven fingers, one for each lost child.

In the opposite base is three-year-old Ilham, way too little for his years, skin peeling off his hands, legs and face. Three years ago, his girlfriend died aged two.

It is too terrible to even glance at one-year-old Asma. She breathes strongly into an air mask that covers most of her little mouth, but she has beautiful hazel eyes and long eyelashes that are wide open and little blinking.

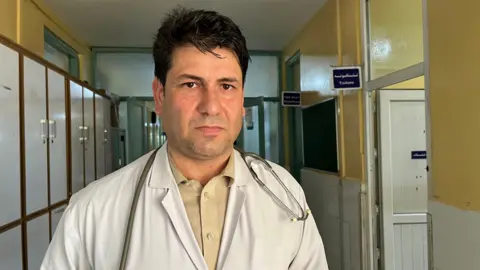

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonDr Sikandar Ghani, who’s standing over her, shakes his head. ” I do n’t think she will survive”, he says. Asma’s little body has gone into toxic shock.

Despite the circumstances, upward until then there was a selflessness in the room- midwives and mother going about their job, feeding the kids, soothing them. It all starts, a cracked look on so many eyes.

Asma’s mom Nasiba is weeping. She leans down to kiss her child while lifting her mask.

” It feels like my brain is melting from my body.” I ca n’t bear to see her suffering like this”, she cries. Nasiba has now lost three babies. ” My husband is a labourer. When he gets job, we eat”.

Dr. Ghani warns that Asma may experience cardiac arrest at any time. We leave the room. Less than an hour after, she died.

More than three children per day have died in Nangarhar’s public health ministry, according to the Taliban’s public health department, in the past six decades. A shocking number, but there would have been many more fatalities if World Bank and Unicef had certainly contributed to the continuation of this program.

Up until August 2021, almost all of Afghanistan’s open heath was funded by foreign funds donated directly to the preceding state.

Due to international punishment, the Taliban were unable to provide the funds when they took control. This triggered a medical decline. Support organizations intervened to provide what was meant to be a temporary crisis answer.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonIt was always an untenable answer, and then, in a universe distracted by so much more, funding for Afghanistan has shrunk. Similarly, the Taliban administration’s policies, particularly its restrictions on women, have meant that sponsors are hesitant to give money.

” We inherited the poverty and malnutrition issue, which has only gotten worse as a result of climate change and natural disasters like floods. The international community should improve humanitarian support, they should not attach it with social and domestic issues”, Hamdullah Fitrat, the Taliban government’s assistant spokesman, told us.

We have visited more than a few health facilities in the nation over the past three years, and we have seen how quickly the condition has deteriorated. During each of our history several visits to institutions, we’ve witnessed children dying.

However, what we have also witnessed is proof that the correct treatment can protect children. Bibi Hajira, who was in a delicate condition when we visited the hospital, is now much better and has been discharged, Dr Ghani told us over the telephone.

” If we had more drugs, infrastructure and staff we may save more children. Our team has strong dedication. We work hard and are ready to complete more”, he said.

” I also have kids. When a child dies, we even suffer. I am aware of what may enter the kids ‘ hearts.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonMalnutrition is not the only factor contributing to a rise in deaths. Kids are also dying from preventable and curable conditions.

In the intensive care unit next entrance to the nutrition hospital, six-month-old Umrah is battling severe bronchitis. As a caregiver adheres a salt flow to her body, she screams violently. Umrah’s family Nasreen sits by her, tears streaming down her face.

” I wish I could die in her position. I’m but scared”, she says. Two weeks after we visited the hospital, Umrah died.

These are the accounts of those who survived hospitalization. Countless others ca n’t. One in five children who require medical care can visit the Jalalabad doctor.

The pressure on the service is so powerful that almost immediately after Asma died, a little girl, three-month-old Aaliya, was moved into the third a mattress that Asma left unfilled.

No-one in the room had time to process what had happened. Another really poor child had to be treated.

The Taliban government estimates that the inhabitants of five provinces, or approximately five million people, is served by the Jalalabad clinic. And now the force is even greater. The majority of the more than 700,000 Afghan refugees who Pakistan has forcibly deported since late last month remain in Nangarhar.

Another alarming statistic released this year by the UN was found in the neighborhoods around the hospital: that 45 % of children in Afghanistan are stunted, or shorter than they should be.

Robina’s two-year-old boy Mohammed don’t remain still and is much shorter than he should be.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen Anderson” He may be good if he receives care for the next three to six months,” the doctor informed me. But we ca n’t even afford food. How do we spend for the therapy”? Robina asks.

She and her family had to leave Pakistan next year, and they now reside in a filthy, clean settlement in the Sheikh Misri region, which is accessible via dirt roads from Jalalabad.

” I’m afraid that he will become disabled and that he will never be able to walk,” Robina says.

” In Pakistan, we even had a difficult life. But there was job. Here my father, a labourer, often finds job. If we were still present in Pakistan, we may had treated him.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonAccording to Unicef, stunting can result in serious, irreversible physical and cognitive deterioration that can last a lifetime and even influence the next generation.

” Afghanistan is now struggling financially. How does our society be able to assist those who are physically or mentally impaired if a sizable portion of our future generation is? asks Dr Ghani.

If Mohammad is treated before it’s too soon, he can be saved from lasting harm.

However, the most drastic cuts have been made to the neighborhood diet programs that aid organizations in Afghanistan have run, with many of them receiving only a quarter of the necessary funding.

BBC/Imogen Anderson

BBC/Imogen AndersonWe encounter individuals with emaciated or stunted children in street after lane of Sheikh Misri.

Sardar Gul has two malnourished children – three-year-old Umar and eight-month-old Mujib, a bright-eyed little son he holds on his shoulder.

” A fortnight ago Mujib’s mass had dropped to less than three tons. We began receiving food capsules once we were able to register him with an assistance organization. Those have definitely helped him”, Sardar Gul says.

Mujib then weighs six kilos- nevertheless a couple of kilos skinny, but considerably improved.

It provides information that saving children from disability and death can be achieved through prompt treatment.

More monitoring: Irene Anderson and Sanjay Ganguly