Thousands of Afghans living in Pakistan raced to the border on Tuesday ahead of a midnight deadline for undocumented foreigners to leave the country.

Pakistan says 1.7 million such people must leave by 1 November or face arrest and deportation. Most are Afghans.

Many refugees are terrified, having fled Afghanistan after the Taliban retook control in 2021. Others have been in Pakistan for decades.

“Where will we go if we are forced to leave Pakistan?” asked one young woman.

Sadia, who has been studying in Peshawar in north-west Pakistan, said she escaped Afghanistan two years ago for a chance at getting an education, after the Taliban government barred girls and women from school under its harsh version of Islamic law.

“I am studying here in Pakistan and I wish to continue my education here. If we are forced to leave, I will not be able to continue my study in Afghanistan. My parents, my sister and brother are scared about the future,” she told BBC Urdu.

Tensions between the countries soared after a spike in cross-border attacks, which Islamabad blames on Afghanistan-based militants.

Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban, who deny providing sanctuary for militants targeting Pakistan, have called the move to deport undocumented Afghans “unacceptable”.

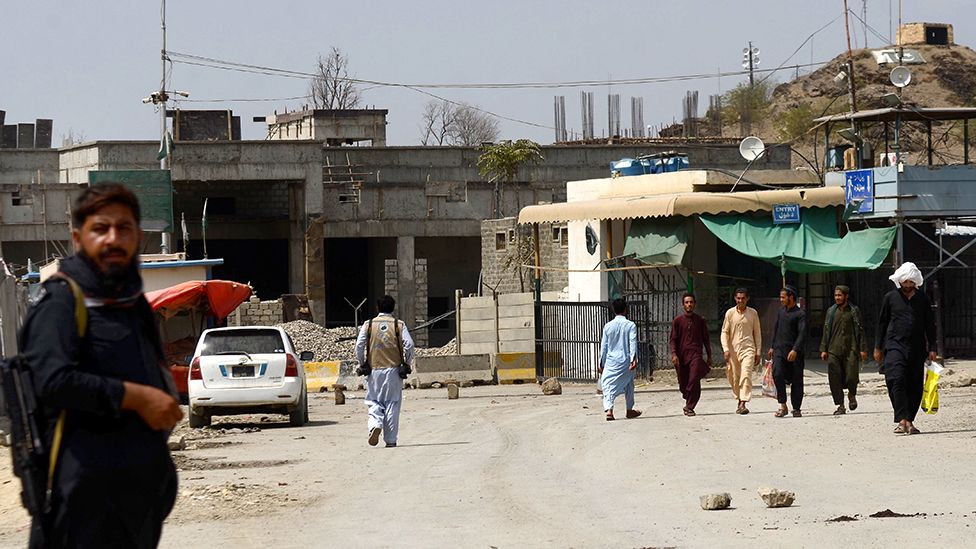

Throngs of refugees rushed to the border with Afghanistan on Tuesday – the last day for them to leave voluntarily or be deported – on trucks overflowing with clothes and furniture.

Close to 200,000 Afghans have returned home as of Monday, Pakistan said. Reports said 20,000 journeyed to the border on Tuesday as time to leave voluntarily ran out.

Eight in 10 who left said they feared being arrested if they stayed, according to a UN report.

Many of these refugees, who fled Afghanistan after the Taliban retook control of the government, fear that their dreams and livelihoods will be crushed – yet again.

But Pakistan, which has been wrestling with an economic crisis in recent years, is short of patience. In July, the Pakistani rupee saw its sharpest drop against the dollar since October 1998.

The UN’s human rights office urged Pakistani authorities to stop deportations to avoid a “human rights catastrophe”.

“We believe many of those facing deportation will be at grave risk of human rights violations if returned to Afghanistan, including arbitrary arrest and detention, torture, cruel and other inhuman treatment,” said Ravina Shamdasani, spokeswoman of the UN’s human rights office.

The Taliban have all but broken their earlier promises to give women the right to work and study – the suppression of women’s rights under their rule is the harshest in the world,

Apart from being banned from school, girls are also not allowed in parks, gyms, pools and other public spaces. Beauty salons have been shut and women are required to be dressed in head-to-toe clothing.

Earlier this year, the Taliban also burned musical instruments, claiming music “causes moral corruption”.

Afghan singer Sohail said he fled the Afghan capital Kabul “with only some clothes” the night the Taliban seized control of the city in August 2021.

“I cannot live as a musician in Afghanistan,” said Mr Sohail, whose family of musicians have been trying to make ends meet in Peshawar.

“We are facing a critical time, as we have no other options, the Taliban do not accept music in Afghanistan and we have no other options for livelihoods,” he said.

The Taliban say they have set up a commission to provide basic services, including temporary accommodation and health services, to returning Afghans.

“We assure them that they will return to their country without any worries and adopt a dignified life,” Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Pakistan has taken in hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees over decades of war. About 1.3 million Afghans are registered as refugees while another 880,000 have received the legal status to remain, according to the UN.

But another 1.7 million people are in the country “illegally”, Pakistan’s Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti said on 3 October, when he announced the expulsion order.

The UN’s figures differ – it estimates that there are more than two million undocumented Afghans living in Pakistan, at least 600,000 of whom arrived after the Taliban returned to power.

Mr Bugti’s order came after a spike in violence near Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan, often involving armed fighters including the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) – often known as the Pakistani Taliban – and the Islamic State militant group.

The minister claimed “14 out of 24” suicide bombings in Pakistan this year were carried out by Afghan nationals.

“There are no two opinions that we are attacked from within Afghanistan and Afghan nationals are involved in attacks on us… We have evidence,” he said according to state media reports.

Unauthorised refugees will be deported if they do not leave, Mr Bugti said on Monday. He stressed the crackdown was not aimed at specific nationalities, but acknowledged that those affected are mainly Afghans.

Earlier in September, Pakistan was hit by two suicide bombings which killed at least 57 people. No group claimed responsibility for the attack, with the TTP denying involvement – though Mr Bugti said one of the suicide bombers had been identified as an Afghan national.