Afghans fleeing the Taliban are being kidnapped and tortured by gangs as they try to cross the border between Iran and Turkey on their way to Europe, a BBC investigation has found. The gangs then send videos of the abuse to the families of migrants being held hostage, demanding a ransom for their release.

Warning: this article contains descriptions of violence and sexual assault that some readers may find disturbing

Shackled together on a mountain-top with padlocks around their necks, a group of Afghan migrants beg for their release.

“Whoever watches this video, I was kidnapped yesterday, they are demanding $4,000 (£3,200) for each one of us. They beat us day and night non-stop,” says one man, with a bloodied lip, his face caked in dust.

Another video shows a group of men fully naked, crawling in the snow as someone whips them from behind.

“I have family, don’t do this to me; I have a wife and children, have mercy, please,” one man cries in another, shortly before he is filmed being sexually abused at knifepoint by one of the gangs.

These disturbing videos are evidence of a growing criminal enterprise, in which gangs in Iran kidnap mainly Afghan migrants trying to make their way to Europe.

The migration route from Afghanistan to Iran, then across the border into Turkey and onto the rest of Europe, has been used for decades. In fact, I took part of the same journey myself 12 years ago when fleeing Iran for the UK, where I was granted asylum.

But the route is now more dangerous than ever.

Those trying to cross from Iran into Turkey walk for hours over dry, mountainous terrain with no trees to provide shade, making it harder to avoid security forces who patrol the area.

As hundreds of thousands have fled Afghanistan since the Taliban seized power in August 2021, gangs have seen an opportunity to profit from the huge increase in the number of people making the journey.

Often in collaboration with the smugglers, they are kidnapping people on the Iranian side of the border, extorting money from vulnerable groups who have often already paid large sums in order to ensure safe passage.

The BBC team heard stories of torture from at least 10 locations along the border. One activist who has been documenting the abuse for the past three years told us he received as many as two or three videos of torture a day at its peak.

In an apartment in Turkey’s commercial capital Istanbul, we meet Amina.

She had a successful career as a police officer in Afghanistan, but fled the country when she realised the Taliban were going to retake power, having received threats before from the group.

Softly-spoken and wearing a purple headscarf, she told me about her experience on the border when she and her family were taken hostage by a gang.

“I was very scared, I was terrified, because I was pregnant and there was no doctor. We had heard many stories of young boys being raped.”

Her father Haji told us the gang sent him a video showing the torture of an unknown Afghan man after they had kidnapped Amina and other members of his family.

“This was the situation I was in. By sending these videos they were warning me. If you don’t pay the ransom we will kill your daughters and your son-in-law,” he says.

Haji sold his house in Afghanistan to pay the gang and get his family released. They then tried again to get into Turkey, this time successfully.

But the eight-day ordeal on the border was too much for Amina.

She lost her baby.

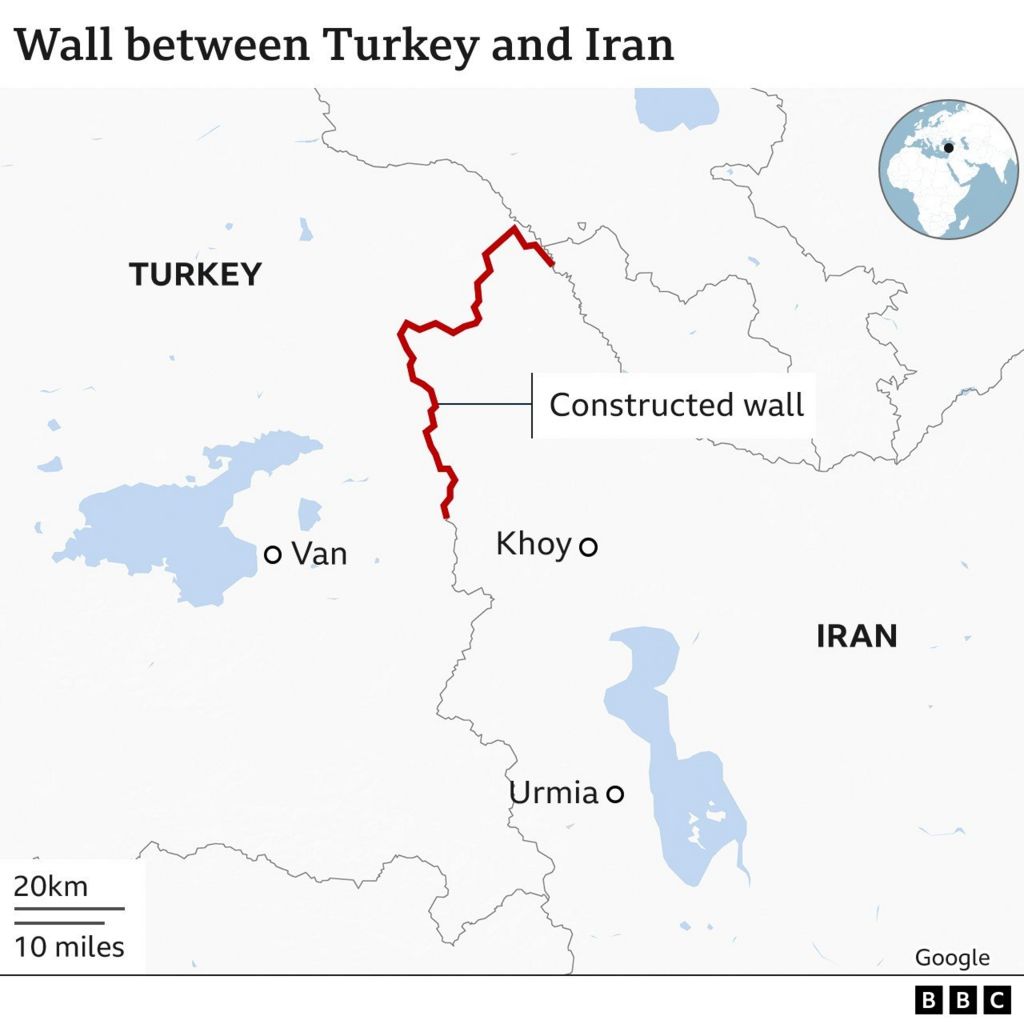

Aside from the gangs, Amina and others face another major obstacle along their route: The wall.

Snaking more than half the length of the Turkish-Iranian border, it stands three metres high and is fortified with barbed wire and electronic sensors and watch-towers by the European Union (EU).

Turkey began building the wall in 2017 in order to stop migrants crossing into the country, but they are still coming.

Amina and several others told us they fell into the hands of violent gangs on the Iranian side after Turkish authorities had pushed them back over the border at night, allegations which have also been documented by international rights groups.

Mahmut Kagan, a Turkish human rights lawyer who represents asylum seekers, insists this practice, which is illegal under international law, is helping the gangs to exploit people.

“It’s very much related to the pushbacks – those violations – because it creates a fragile group open to all forms of abuses,” he says.

Turkish authorities did not respond to the BBC’s request for comment about these allegations. But in the face of similar accusations from human rights groups the government has denied pushbacks, saying any activities to prevent illegal entry into Turkey are carried out within the scope of border management.

Before the wall was built, many locals used to make a living by smuggling goods across the border. That trade has largely vanished now, meaning some have switched to kidnapping or trafficking migrants instead.

In Van, the closest Turkish city to the Iranian border and a hub for migrant trafficking, we met a young Afghan man called Ahmed in a stable repurposed as a safehouse, as he negotiated the next leg of his journey with smugglers.

Ahmed’s brother was kidnapped on the Iranian side of the border with his extended family when they tried to flee the Taliban last year.

It was Ahmed, then still in Afghanistan, who received the calls from the gang demanding a ransom.

“I said we don’t have money, the kidnapper was beating my brother. We could hear it down the line,” he says.

Ahmed sold his family’s belongings to pay for their release. But the experience wasn’t enough to stop him trying the same journey himself six months later, desperate to make a living after the economic crisis that followed the Taliban takeover.

In the Afghan capital Kabul, we met Said, back where he started after six failed attempts to escape Afghanistan and make it to Turkey.

He had been promised a fake document that would allow him to cross to Turkey. Instead he says he was betrayed by his contact and sold to a gang, who tortured him and demanded a $10,000 (£7,990) ransom.

“I was very scared. They could do anything to me. Take out my eyes, sell my kidneys, take out my heart,” he says.

But he told us it was his dignity that he feared losing the most, after he overheard the gang discussing how they could rape him and send the video to his family back home.

Eventually, he escaped after paying $500 (£400).

We asked the Iranian government what was being done to crack down on the gangs’ activities along the border, but we did not receive a response.

The BBC is banned from reporting inside Iran, so we were not able to cross the border to investigate further.

Weeks after our interview, Said contacted us to tell us that he was back on the move and had reached Tehran again. That was eight months ago – and we have not heard from him since.

Others we met who did make it to Turkey, like Amina, are trying to look to the future with optimism.

“I won’t give up. I know I’ll become a mother,” she says. “I know I’ll be strong.”

We have changed the names of some interviewees in this report for their security.

Edited by Hugo Williams