BBC

BBCA young girl is sheltered under a tree between two active streets, clutching a stack of documents in her lap.

These pieces of paper represent Bibi Nazdana’s decision to divorce herself after a two-year legal struggle to break her from career as a child bride. They are more significant than anything else in the world.

They are the same documents that a Taliban court has invalidated, a result of the group’s hardline interpretation of Sharia ( religious law ), which has effectively made women invisible in Afghanistan’s legal system.

Zedana’s marriage is one of the hundreds of court decisions that have been annulled since the Taliban’s rule this quarter three years ago.

The woman was promised at age seven to petition the courts to reverse the divorce decree she had fought so hard for, but they only swept into Kabul and swept into the money in just ten days.

When Nazdana was 15 years old, Hekmatullah had first appeared to desire his family. It was eight years since her parents had agreed to what is known as a’bad wedding’, which seeks to change a community “enemy” into a “friend”.

She repeatedly told the court she could n’t marry the farmer, who is now in his 20s, and then went to the court, who was then operating under the US-backed Afghan government. After two decades, a decision was made in her favor:” You are then separated and free to marry whomever you want. ‘”

However, Nazdana was informed that she would not be able to bring her own situation in people after Hekmatullah appealed the decision in 2021.

” At the court, the Taliban told me I should n’t return to court because it was against Sharia. They said my brother may represent me otherwise,” says Nazdana.

” They told us if we did n’t comply,” says Shams, Nazdana’s 28-year-old brother,” they would hand my sister over to him ( Hekmatullah ) by force. “

Her previous partner, and then a recently signed up part of the Taliban, won the case. Shams ‘ pleas for a court hearing about her life’s risk to Uruzgan, their home state, were deaf on deaf ears.

The siblings figured they had to retreat after being left with no choice.

When the Taliban came back to power three years ago, they promised to end the problem of the past and bring about” fairness” under Sharia, a branch of Islamic law.

Since then, the Taliban say they have looked at some 355,000 circumstances.

Most were legal situations- an estimated 40 % are disputes over land and a further 30 % are family problems including marriage, like Nazdana’s.

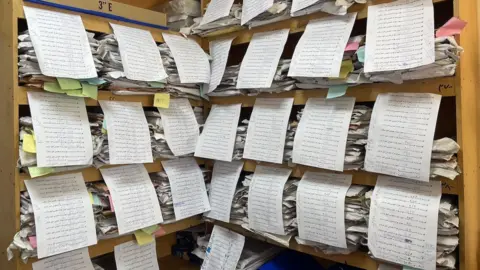

After the BBC had snagged exposure to the Supreme Court’s up practices in the funds, Kabul, the divorce decree was made.

Abdulwahid Haqani- advertising agent for Afghanistan’s Supreme Court- confirms the decision in favour of Hekmatullah, saying it was not true because he “was n’t existing”.

” The earlier corrupt government’s decision to withdraw Hekmatullah and Nazdana’s union was against the Sharia and principles of relationship,” he explains.

However, the fairness system’s purported reforms have gone beyond merely reopening settled cases.

Additionally, the Taliban have consistently replaced all magistrates with those who support their conservative beliefs, both male and female.

Additionally, people were declared unfit to practice law.

Because of our Sharia principles, the judiciary work requires people with high intelligence, says Abdulrahim Rashid, director of foreign relations and communications at Taliban’s Supreme Court.” Women are n’t qualified or able to judge.

For the women who worked in the program, the damage is felt seriously- and not just for themselves.

If there are no people in the courts, then there is little chance for women’s privileges to strengthen under the law, according to previous Supreme Court judge Fawzia Amini, who fled the country after the Taliban returned.

” We played an important role,” she says. ” For instance, the Elimination of Violence against Women rules in 2009 was one of our efforts. We also worked on the anti-human smuggling rules, orphan guardianship, or the regulation of women’s shelters, to name a few. “

She even rubbishes the Taliban overturning past decisions, like Nazdana’s.

” If a person divorces her father and the court records are presented as evidence, therefore that’s last. Legal verdicts ca n’t change because a regime changes,” says Ms Amini.

” Our legal code is more than half a century old,” she adds. It has been used since before the Taliban were established.

” All civic and penal code, including those for marriage, have been adapted from the Quran. “

But the Taliban say Afghanistan’s former rulers simply were n’t Islamic enough.

Instead, they largely rely on Hanafi Fiqh ( jurisprudence ) religious law, which dates back to the 8th Century – albeit updated to “meet the current needs”, according to Abdulrahim Rashid.

” The former judges made judgments based on the penal and civil password.” However, Sharia [ Islamic law ] is now the basis for all decisions, he continues, proudly gazing at the number of cases they have already sorted.

Ms Amini is less impressed by the plans for Afghanistan’s legal program going ahead.

” I have a problem for the Taliban. Based on these rules or the laws their sons will adopt, did their parents get married? ” she asks.

Nazdana finds no satisfaction in living between two streets in the unknown neighboring country.

She has been here for a month, clutching her marriage documents, and hoping someone will assist her. She is now just 20.

” I have knocked on several doors asking for help, including the UN, but no-one has heard my voice,” she says.

” Where is the help? Do n’t I deserve freedom as a woman? “