World Service, BBC

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe picturesque town of Sergele is nestled in the highlands of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Local people have foraged in the nearby forests for exotic fruits and spices and have foraged for generations to make a living growing pomegranates, almonds, and peaches.

But Sergele, located 16km ( 10 miles ) from the border with Turkey, has become increasingly surrounded by Turkish military bases, which are dotted across the slopes.

One looms over the town while perched half up the western hill, and the other is being constructed in the south.

Over the past two years, there have been at least seven constructions in Sergele, including one that is being supervised by a little bridge, which keeps the village from accessing the area.

” This is 100 % a form of occupation of Kurdish [Iraqi Kurdistan ] lands,” says farmer Sherwan Sherwan Sergeli, 50, who has lost access to some of his land.

The Turks “ruined it,” they said. “”

Phil Caller

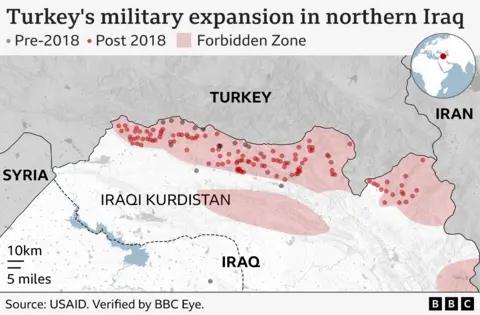

Phil CallerSergele is now in danger of being dragged into what’s known locally as the” Forbidden Zone”- a huge strip of land in northwestern Iraq affected by Turkey’s conflict with the Kurdish militant group the PKK, which launched an insurrection in southwestern Turkey in 1984.

Nearly the entire length of the Iraqi-Turkish border is covered in the Forbidden Zone, which can be found up to 40 kilometers ( 25 miles ) deep in some places.

According to the human rights organization Community Peacemaker Teams, hundreds of residents have been killed by helicopter and airstrikes in and around the Forbidden Zone. According to a 2020 Kurdistan political statement, thousands have been forced off their property and whole settlements have been emptied out by the issue.

Sergele is then effectively on the front lines of Turkey’s conflict with the PKK.

When the World Service, BBC Eye Investigations team visited the area, Turkish aircraft pummelled the mountains surrounding the village to root out PKK militants, who have long operated from caves and tunnels in northern Iraq.

Much of the area around Sergele had been burned by shooting.

The more outposts they put up, Sherwan says,” the worse it gets for us.”

Turkey’s military presence in the Forbidden Zone has rapidly increased in recent years, but the extent of this growth has not yet been made public.

Using satellite pictures assessed by professionals and corroborated with on-the-ground monitoring and open-source information, the BBC found that as of December 2024, the Greek government had built at least 136 fixed government setups across northern Iraq.

Turkey currently holds de facto control over more than 2,000 sq km ( 772 square miles ) of Iraqi land thanks to its extensive network of military bases, according to the BBC’s analysis.

Further, satellite images reveal that the Turkish military has constructed at least 660 kilometers ( 410 miles ) of roads connecting its facilities. These offer routes have resulted in forest and left a lasting impression on the country’s hills.

Although a few of the foundations date back to the 1990s, 89 % have been constructed since 2018, which marked Turkey’s first significant military presence in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Greek government did not respond to the BBC’s pleas for interviews, but it has maintained that its military installations are required to halt the PKK, which Ankara and a number of European nations, including the UK, have labeled as terrorist organizations.

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe sub-district investment of Kani Masi, which is only 4km ( 2. A 5 miles ( or 5 miles ) from the Forbidden Zone and parts thereof may provide a glimpse into Sergele’s future.

Some people still live here today, despite the city’s reputation for producing apples.

Farmer Salam Saeed, whose property is in the shadow of a large Greek foundation, hasn’t been able to cultivate his garden for the past three decades.

He claims that” the time you get around, you will have a drone hover over you.”

They did take you if you persist. “”

In the 1990s, the Turkish army was the first to establish base here, and it has since grown stronger.

The main military base of Sergele, which has concrete blast walls, contact towers, and room for moving armored personnel carriers, is much more advanced than the smaller outposts nearby.

Salam, like some other visitors, believes Turkey eventually wants to claim the place as its own.

He goes on to say that” all they want is for us to keep these locations.”

Phil Caller

Phil CallerSmall influence

Near Kani Masi, the BBC saw first-hand how Turkish troops have effectively pushed back the Iraqi border watch, which is responsible for protecting Iraq’s international boundaries.

Border guards were strategically positioned properly inside Syrian territory, directly in front of Turkish troops, able to enter the border immediately and possibly risk a clash at various locations.

General Farhad Mahmoud points to a ridge just across a valley, about 10 kilometers ( 6 miles ) inside Iraqi territory, saying,” The posts that you see are Turkish posts.

But” we may reach the frontier to know the number of content”, he adds.

Turkey’s military development in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is fueled by its fall as a helicopter energy and growing defense budget, is seen as a result of a wider global shift in interventionism.

Turkey has even attempted to establish a buffer zone along its border with Syria in response to its activities in Iraq and to stop the PKK-linked Arab military teams.

In people, Iraq’s state has condemned Turkey’s military presence in the country. However, it has managed to meet some of Ankara’s requires behind closed doors.

A memorandum of understanding to battle the PKK together was signed by the two parties in 2024.

But the record, obtained by the BBC, did not place any restrictions on Turkish soldiers in Iraq.

Turkey’s dependence on it for trade, investment, and water security has grown even worse as a result of its damaged internal politics, which has further eroded the ability of the government to take a strong stand.

The BBC requested comment on the report, but Iraq’s federal authorities did not.

However, the leaders of the semi-autonomous area of Iraqi Kurdistan have a close relation with Ankara based on mutual pursuits and have often downplayed the human damage due to Turkey’s military actions.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG ), an arch enemy of the PKK, is under the control of the Kurdistan Democratic Party ( KDP ), which has been in power since 2005, when Iraq’s constitution granted the region its semi-autonomous status.

The KDP’s close ties to Turkey have helped the region’s economic growth and strengthened its standing both against its regional political rivals and against the Iraqi government in Baghdad, which it tussles for greater autonomy.

Hoshyar Zebari, a senior member of the KDP’s politburo, sought to blame the PKK for Turkey’s presence in Iraqi Kurdistan.

He told the BBC,” They [the Turkish military ] are not harming our people.”

They are not holding them hostage. They are not interfering in them going about their business. Their main concern, and only goal, is the PKK. “”

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe conflict shows no signs of ending, despite the PKK’s long-jailed leader Abdulla Ocalan calling in February for his fighters to lay down arms and disband.

Turkey has continued to shell targets throughout Iraqi Kurdistan, and the PKK has claimed responsibility for the PKK’s drone downing last month.

In addition, violent incidents in Turkey have decreased since 2016, according to the NGO Crisis Group, but those in Iraq have increased, with civilians living in the border region facing growing displacement and death risks.

One of those killed was 24-year-old Alan Ismail, a stage-four cancer patient hit by an air strike in August 2023 while on a trip to the mountains with his cousin, Hashem Shaker.

A police report obtained by the BBC attributes the incident to a Turkish drone, despite the Turkish military’s claim that it carried out a strike that day.

Hashem and his family dispute the allegations he and his family made when he complained about the attack in a local court, where he was detained by Kurdish security forces and held for eight months on suspicion of supporting the PKK.

” It has destroyed us. It’s like killing everyone in the family, says Alan’s father, Ismail Chichu.

They [the Turks ] do not have the right to murder people in their own country or on their own land. “”

The BBC contacted Turkey’s defense ministry for comment, but it did not respond. It has previously told the media that the Turkish armed forces strictly adhere to international law and that they only plan and carry out operations against terrorists while taking precautions to protect civilians.

Phil Caller

Phil CallerThe BBC has seen documents suggesting Kurdish authorities may have acted to help Turkey evade accountability for civilian casualties.

A Kurdish court closed the investigation into Alan’s murder, according to confidential documents obtained by the BBC, claiming the perpetrator was unknown.

And according to his death certificate, which was obtained by Kurdish authorities and obtained by the BBC, he died from “explosive fragments.”

Failing to mention when victims of air strikes have died as a result of violence, rather than an accident, makes it difficult for families to seek justice and compensation, to which they’re entitled under both Iraqi and Kurdish law.

According to Kamaran Othman from Community Peacemaker Teams, “in the majority of the death certificates, they only write “infijar,” which means explosion.

It can explode in any number of ways.

” I think the Kurdish Regional Government doesn’t want to make Turkey responsible for what they are doing here. “”

The PKK and the Turkish army’s military conflict in the area was the result of” tragic loss of civilians,” according to the KRG.

It added that” a number of casualties” had been documented as” civilian martyrs”, meaning they have been unjustly killed and entitling them to compensation.

His family is still waiting, at least for the KRG to acknowledge Alan’s death, almost two years after his death.

We don’t need their compensation, Ismail says.” They could at least send their condolences.

” When something is gone, it’s gone forever. “”