BBC Burmese

BBC

BBCAbout 15 son’s packs lie torn apart in the wreckage- red, blue and orange luggage with publications spilling out of them.

Spiderman games and letters of the alphabet are scattered among broken seats, furniture and garden presentations at the remnants of this school destroyed by the great earthquake that hit Myanmar on Friday.

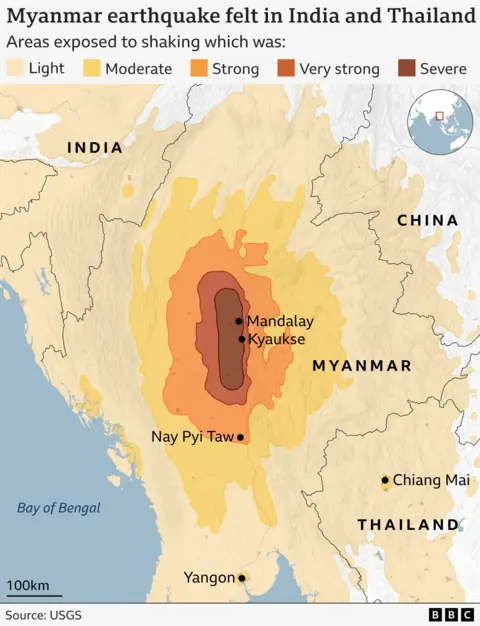

It is in the town of Kyaukse, about 40km ( 25 miles ) south of Mandalay, one of the areas hit hardest by the 7.7 magnitude quake that killed at least 2, 000 people.

Kywe Nyein, 71, cried as he explains that his relatives are preparing to carry the death of his five-year-old daughter, Thet Hter San.

He says her mother was having breakfast when the devastating disaster began. She ran to the class, but the tower had collapsed entirely.

The little woman’s body was found about three hours later. ” Luckily, we got our lover’s brain alive, in one piece”, he says.

Citizens say there were about 70 kids, aged between two and seven, at the university on Friday, learning pleasantly. But now there is much left except a pile of masonry, material and metal rods.

The university says 12 kids and a professor died, but citizens believe the number is at least 40- that is how many were in the upstairs area that collapsed.

People and kids are distraught. People say the entire town came to help with the recovery work and many bodies were retrieved on Friday. They describe mother crying and calling out the labels of their children much into the evening.

Today, three days later, the site is calm. Individuals look at me with pain etched on their heads.

Support groups are warning of a worsening humanitarian crises in Myanmar, with hospitals damaged and overwhelmed, though the entire level of devastation is also emerging.

Before we arrived in Kyaukse, we had been in the capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

The worst-hit area we saw there was a building that had been residential quarters for civil servants. The whole ground floor had collapsed, leaving the three upper floors still standing on top of it.

There were traces of blood in the rubble. The intense stench suggested many people had died there, but there was no sign of rescue work.

A group of policemen were loading furniture and household goods on to trucks, and appeared to be trying to salvage what was still useable.

The police officer in charge would not give us an interview, though we were allowed to film for a while.

We could see people mourning and desolate, but they did not want to speak to the media, fearing reprisals from the military government.

We were left with so many questions. How many people were under the rubble? Could any of them still be alive? Why was there no rescue work, even to retrieve the bodies of the dead?

Just 10 minutes ‘ drive away, we had visited the capital’s largest hospital- known here as the “1, 000-bed hospital”.

The roof of the emergency room had collapsed. At the entrance, a sign saying” Emergency Department” in English lay on the ground.

There were six military medical trucks and several tents outside, where patients evacuated from the hospital were being cared for.

The tents were being sprayed with water to give those inside some relief from the intense heat.

It looked like there were about 200 injured people there, some with bloodied heads, others with broken limbs.

We saw an official angrily reprimanding staff about other colleagues who had not turned up to work during the emergency.

I realised the man was the minister for health, Dr Thet Khaing Win, and approached him for an interview but he curtly rejected my request.

On the route into the city, people sat clustered under trees on the central reservation of the highway, trying to get some relief from the hot sun.

It is the hottest time of year- it must have been close to 40C- but they were afraid to be inside buildings because of the continuing aftershocks.

We had set out on our journey to the earthquake zone at 4am on Sunday morning from Yangon, about 600 km ( 370 miles ) south of Mandalay. The road was pitch black, with no street lights.

After more than three hours ‘ driving, we saw a team of about 20 rescue workers in orange uniforms, with logos on their vests showing they had come from Hong Kong. We started to find cracks in the roads as we drove north.

The route normally has several checkpoints, but we had travelled for 185km ( 115 miles ) before we saw one. A lone police officer told us the road ahead was closed because of a broken bridge, and showed us a diversion.

We had hoped to reach Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city, by Sunday night.

But the diversion, and problems with our car in the heat, made that impossible.

A day later, we have finally reached the city. It is in complete darkness, with no street lights on and homes without power or running water.

We are anxious about what we will find here when morning comes.