BBC News, Mumbai

Getty Images

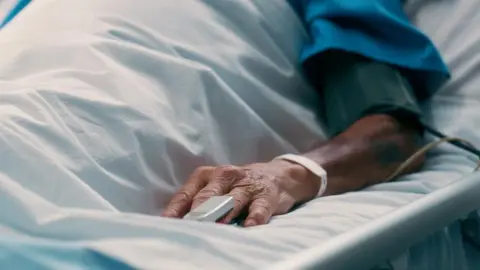

Getty ImagesIn 2010, Internet Yadev, a physician from the southern Indian state of Kerala, was confronted with one of the hardest choices of his career.

He had to choose between keeping his dad- a terminal cancer persistent- dead, and honouring his wish, expressed orally, to cease all treatments and put an end to his suffering.

Warning: This article contains some troubling information

” As a child, I felt it was my responsibility to do whatever I had to extend my father’s career. He became uneasy as a result, and he ultimately died by himself in an intensive care facility. His bones were crushed by the doctor’s most recent attempts to revive him using CPR. It was a hideous death”, Dr Yadev says.

The experience, he says, deeply impacted him and helped him realise the importance of advance medical directives ( AMDs ), also known as living wills.

A living will is a lawful document that enables a person over the age of 18 to choose the health care they want to get if they become terminally ill or frail without any chance of recovery and are unable to make any decisions on their own.

For instance, they may designate that they don’t want to be put on life-support systems or insist that they want to get given sufficient pain-relieving treatment.

In 2018, India’s Supreme Court allowed people to draw up living wills and thereby choose passive euthanasia, where medical treatment can be withdrawn under strict guidelines to hasten a person’s death. Active euthanasia – any act that intentionally helps a person kill themselves – is illegal in the country.

But despite the legal go-ahead, the concept of living trusts hasn’t actually taken off in India. Researchers say that this has much to do with the means Indians talk, or rather, don’t talk about death. Death is frequently viewed as prohibited, and any mention of it is thought to have bad luck.

However, there are currently efforts being made to transform this.

In November, Dr. Yadev and his team launched India’s second program at the Government Medical College in Kerala’s Kollam city to teach people about living trusts by providing details both in person and over the phone. Volunteers also distribute can templates and run awareness campaigns.

Internet Yadev

Internet YadevFamily people must have transparent and fair conversations about suicide when creating a living will. Despite some weight, activists and organizations are taking actions to increase awareness, and there’s a growing, though careful, attention.

Kerala leads the way in these conversations. Currently, it has the country’s best palliative care network, and organisations that offer end-of-life care have also started awareness campaigns around living wills.

In March, around 30 people from the Pain and Palliative Care society in Thrissur city signed living wills. Dr E Divakaran, founder of the society, says that the gesture is aimed at make the idea more popular among people.

The majority of people have never heard of the term, so they have some inquiries, including those about whether such a mandate can be abused or if their wills may be changed in the future, according to Mr. Yadev, noting that most questions have been made by people in their 50s and 60s.

” Right then, it’s the educated, upper-middle school that’s making use of the service. But with outreach awareness activities, we’re expecting the statistical to widen”, he says.

According to the Supreme Court order, a man must review the would, sign it in the presence of two witnesses, and have it attested by a bank or designated officer. A version of the will must then be submitted to a condition government-appointed steward.

Although the instructions are on paper, many state governments have not yet set up the systems to put them into practice. Dr. Nikhil Datar, a gynecologist from Mumbai city, realized this when he made his living did two years ago because there was no custodian to whom he could post it.

Nikhil Datar

Nikhil DatarBut he sued, and as a result, the Maharashtra government appoints about 400 authorities across state-wide as life will custodians.

In June, Goa state implemented the Supreme Court’s orders around living wills and a high court judge became the first person in the state to register one.

On Saturday, Karnataka state ordered district health officers to nominate people to serve on a key medical board required to certify living wills. [Two medical boards have to certify that a patient meets necessary criteria for the implementation of a living will before medical practitioners can act on it.]

Additionally, Mr. Datar is in favor of a global, centralized modern store for living wills. Additionally, he has provided his own would as a free template on his site. He thinks a may prevents issues for both caregivers and physicians when a person is in a comatose state and after recovery.

Family members frequently refuse to let a client go for more therapy but instead choose to keep them in the hospital because they are unable to care for them at home. Physicians, bound by skilled morality, didn’t deny treatment, so the patient ends up suffering with no way to express their desires”, Mr Datar says.

Living trusts aren’t really about choosing silent death. Dr. Yadev recalls a situation where a man wanted his will to say that he should be placed on life support if his situation possibly lacked such a thing.

He explained that his only baby was residing worldwide and that he didn’t want to pass away until his brother met him, according to Mr. Yadev. You are free to decide how you want to pass away. Why not practice one of the greatest rights that are available to us? he says.

According to care activists, palliative care discussions are starting to take off in the nation, giving an incentive to living wills.

The Delhi All India Institute of Medical Sciences ‘ Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar claims that the doctor is opening a division to teach people about living wills. ” Ideally, doctors may explain living wills with people, but there’s a connection gap”, she says, adding that teaching specialists for these conversations can help assure a person dies with dignity.

According to Mr. Yadev,” Throughout our lives, our decisions are influenced by the wishes of our loved ones or by what society believes is appropriate.”

Let us make choices that are both in our best interests and completely our own, at least in death.