Reuters

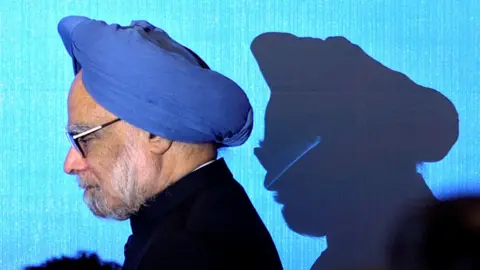

ReutersIt’s difficult to imagine the possibility of a timid politician. Unless Manmohan Singh is the legislator that is in charge.

Since the death of the former Indian prime minister on Thursday, much has been said about the “kind and soft-spoken politician” who changed the course of Indian history and impacted the lives of millions.

His position funeral is scheduled for Saturday, and India’s state has set a seven-day official mourning phase.

Singh didn’t come across as a big-stage politician, lacking the common flair of many of his contemporaries, despite having an illustrious career ( he was governor of India’s central banks and federal finance secretary before becoming a two-term prime minister ).

Even though he conducted interviews and kept press conferences, especially during his first year as prime minister, he decided to remain silent despite scandals and allegations that his cabinet ministers were under investigation for corruption.

His magnanimous behavior was adored in equal measure with his deplorable manners.

Reuters

ReutersHis admirers said he was careful not to pick unnecessary battles or make lofty promises and that he focused on results – perhaps best exemplified by the pro-market reforms he ushered in as finance minister which opened India’s economy to the world.

“I don’t think anyone in India believes that Manmohan Singh can do something wrong or corrupt,” his former colleague in the Congress party, Kapil Sibal, once said,. “He was extremely cautious, and he always wanted to be on the right side of the law.”

His competitors, on the other hand, mocked him, saying he exhibited a kind of ambiguity impractical for a lawmaker, let alone the top of a nation of more than one billion individuals. His voice- hoarse and breathless, about like a weary whisper- usually became the butt of jokes.

However, some people who found him relevant in a political climate where high-pitched and high-octane remarks were common found the words to be endearing.

Singh’s picture as a media-shy, modest, shy politician never left him, even when his peers, including his own party users, went through spectacular cycles of transformation.

However, it was the dignity with which he handled every circumstance, yet the challenging kinds, that made him so wonderful.

Born to a bad community in what is now Pakistan, Singh was India’s second Hindu prime minister. His personal history, a Cambridge and Oxford-educated analyst who overcame unimaginable chances to rise to the top, and his portrayal of an honest and sincere chief, had already earned him a warrior among India’s middle classes.

He surprised people when he publicly apologised in congress for the riots in 1984, which resulted in the deaths of around 3, 000 Sikhs.

The protests, in which several Congress group members were accused, broke out after the death of then-prime secretary Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. Later, one of them claimed to have shot the Congressman to kill a military retaliation she had ordered against separatists hiding in Amritsar, Sikhism’s most holy church.

It was a strong proceed- no other prime minister, including from the Congress group, had gone so far as to offer an apology. However, it gave the Sikh area a therapeutic touch, and elected officials from all political parties praised him for his bravery.

Reuters

ReutersAfter signing a landmark agreement with the US that ended India’s decades-long nuclear loneliness and gave it access to nuclear energy for the first time since it conducted tests in 1974, Singh’s understated style of leadership gained more compliments in 2008 thanks to his understated leadership style.

The offer was substantially criticised by opposition officials and Singh’s personal friends, who feared it would sacrifice India’s international policy. Singh, however, managed to salvage both his state and the offer.

World economic upheaval occurred during the years 2008-2009, but Singh’s policies were credited with preventing it for India.

In 2009, he led his party to a resounding victory and returned as the PM for a second term, cementing his image of a benevolent leader, or rather, the exciting idea that leaders could be benevolent.

For some, he had become morality personified, the “reluctant perfect secretary” who stayed clear of the spotlight and refused to make any serious movements, but was also not afraid of taking courageous decisions for the sake of his country’s future.

Then, things began to unravel.

The Congress party and Singh’s government were plagued by a number of corruption allegations, first one involving the Commonwealth Games ‘ hosting, then the illegal allocation of coal fields. Some of these allegations of corruption later revealed to be false or exaggerated. Some cases from that time are still pending in court.

However, Singh was already feeling some pressure. During his tenure, he made several attempts at reconciliation with India’s arch rival neighbour Pakistan, hoping for a thaw in the decades-old frosty relations.

The approach was sharply questioned in 2008 when a terror attack led by a Pakistan-based terror group killed 171 people in Mumbai city.

The 60-hour siege, one of the bloodiest in the country’s history, opened a chasm of allegations, as the opposition blamed the government’s “soft stance” on terrorism for the tragedy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the coming years, other decisions Singh made badly backfired.

In 2011, an anti-corruption movement led by social activist Anna Hazare shook up Singh’s government. The frail 72-year-old became an icon for the middle classes, as he demanded stringent anti-corruption laws in the country.

As a middle-class hero himself, Singh was expected to deal with Hazare’s demands more perceptively. Instead, the prime minister tried to quash the movement, allowing the police to arrest Hazare and disband his demonstration.

The action sparked a flurry of hostility toward him in the media and the public. People who had once admired his understated style began to doubt whether they had misinterpreted the politician and began to see his quiet ways through a less kind of lens.

The feeling grew even more severe the following year when Singh forbids comment on the horrific gang rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi.

To make things worse, India’s economic growth was slowing. Corruption grew and jobs shrank, sparking waves of public anger. And Singh’s unassuming personality, which once made his every move seem like a revelation, was labelled as showing complacency, diffidence and even arrogance by some.

However, Singh remained silent about his criticism and never attempted to defend or explain himself.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat was until 2014. At a rare news conference, he announced that he would not seek a third term in office.

But he also tried to set the record straight. After citing some of his most notable accomplishments, he said,” I honestly believe that history will judge me more kindly than the contemporary media, or for that matter, the opposition parties in parliament.”

He was right.

As it turned out, neither Singh nor the Congress were able to fully recover from the harm caused by their election defeat to the BJP in the general elections. But despite the many hurdles, Singh’s image as a kind and discerning leader stayed with him.

He maintained a sense of personal dignity and integrity throughout his tenure as prime minister, despite a second term rife with controversy.

His policies were seen to centre around the middle class and the poor – he approved manifold increase in salaries of central employees, kept inflation in check and introduced landmark schemes on educations and jobs.

It might not have been enough to save him from some of his career’s failures or shield him from the difficulties of politics.

But there was more to his shyness, he was a leader of steely resolve.