Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen a judge declared Iwao Hakamata stupid in September, the nation’s longest-serving death row inmate seemed unable to understand, much less relish the instant.

” I told him he was acquitted, and he was silent”, Hideko Hakamata, his 91-year-old girl, tells the BBC at her house in Hamamatsu, Japan.

” I don’t tell whether he understood or no”.

Since Hideko was found guilty of murdering her brother four times in 1968, she had spearheaded her son’s lawsuit.

In September 2024, at the age of 88, he was suddenly acquitted- ending Japan’s longest running legal story.

Mr Hakamata’s situation is impressive. It also highlights the widespread cruelty that underlies Japan’s justice system, where death row prisoners are merely briefed on their hangings a few hours in advance and remain doubtful whether their final day will be their past.

Such care has long been criticized as cruel and inhumane by human rights advocates, who claim it raises the risk of serious mental illness in prisoners.

And more than half a life spent in solitary confinement, waiting to be executed for a murder he didn’t commit, took a heavy toll on Mr Hakamata.

He has been living in Hideko’s near attention since receiving a retrial and being freed from prison in 2014.

When we arrive at the house, he is out for his daily exercise with a volunteer organization that helps the two older siblings. He is anxious around neighbors, Hideko explains, and has been in “his own world” for decades.

” Maybe it can’t be helped”, she says. ” This is what happens after you spend more than 40 years cramming up a tiny prison body.”

” They made him sit like an creature.”

Living on death row

Iwao Hakamata, a former professional wrestler, was examining the body of his employer, the man’s wife, and their two young children while they were employed in a mud processing plant. All four of the victims had been fatally stabbed.

Authorities accused Mr Hakamata of murdering the family, setting their house in Shizuoka alight and stealing 200, 000 yen ( £199,$ 556 ) in cash.

We had no idea what was happening, Hideko recalls the day when officers arrived to arrest her nephew in 1966.

The family house was searched, as well as the properties of their two elder sisters, and Mr Hakamata was taken away.

He immediately denied all expenses, but eventually made what he later described as a coerced statement following beatings and interviews that lasted up to 12 hours a day.

Mr. Hakamata was found guilty of murder and fire and given a death sentence two decades after his arrest. Hideko noticed a change in his demeanor when he was moved to a death row battery.

One special prison visit stands out.

” He told me,’ there was an implementation yesterday- it was a man in the next cell’,” she recalls”. He instructed me to get attention, but from that point on, he completely changed his perspective and sat quietly.

Residents on Japan’s death row, where they wake each day without knowing if it will be their final, are not the only ones whose lives have been ruined by life.

” Between 08: 00 and 08: 30 in the morning was the most crucial moment, because that was normally when prisoners were notified of their murder,” Menda Sakae, who spent 34 decades on death row before being exonerated, wrote in a book about his experience.

Because you don’t know if they will stop in front of your body, you begin to experience the most terrible stress. How dreadful of a sense was this, is it impossible to describe?

James Welsh, lead author of a 2009 Amnesty International report into situations on death row, noted that” the routine threat of imminent death is cruel, horrible and degrading”. Residents were identified as having” considerable mental health issues,” according to the report’s conclusion.

As time went on, Hideko had just watch as her own son’s mental health deteriorated.

” When he asked me’ Do you know who I am?’ I said,’ Yes, I do. You are Iwao Hakamata’. ‘ No,’ he said,’ you must be here to see a distinct people’. And he just went back]to his cell].”

Hideko rose to the occasion to become his main activist and spokesperson. It wasn’t until 2014, yet, that there was a milestone in his case.

Red-stained clothing discovered in a mud tank at Mr. Hakamata’s workplace was a crucial piece of evidence against him.

The trial claimed that he had them when they were recovered a month and two weeks after the killings. However, Mr. Hakamata’s defense team has been fighting for years that the DNA from the attire did not match his and that the information was planted.

In 2014, they were able to inspire a judge to let him go of jail and order him to go on trial again.

Due to protracted legal proceedings, it took until past October for the lawsuit to start. When it eventually did, it was Hideko who appeared in court, pleading for her son’s career.

Mr Hakamata’s death hinged on the scars, and especially how they had aged.

The defense argued that the body would had turned black after being mud for so long, despite the prosecution’s claim that the clothes were red when they had been recovered.

That convinced presiding judge Koshi Kunii, who claimed that” the investigating power had added body spots and hid the objects in the mud container well after the incident took place.”

Judge Kunii more found that another data had been fabricated, including an analysis report, and declared Mr Hakamata honest.

Hideko’s initial response was to weep.

” When the judge said that the defendant is not guilty, I was elated, I was in grief,” she says”. I am certainly a sad people, but my grief really flowed without stopping for about an hour.”

Hostage righteousness

The judge’s summary that Mr. Hakamata’s evidence was fabricated raises unsettling issues.

Japan has a 99 % faith price, and a method of so-called” hostage justice “which, according to Kanae Doi, Japan director at Human Rights Watch”, denies people arrested their right to a presumption of innocence, a fast and good parole hearing, and access to lawyers during questioning”.

” These abusive practices have resulted in lives and families being torn apart, as well as wrongful convictions,” Mr Doi noted in 2023.

For the past 30 years, David T. Johnson, a professor of sociology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, has followed the Hakamata case closely. His research focuses on criminal justice in Japan.

He claimed that one reason it dragged on was that” critical evidence for the defence was not disclosed to them until around 2010″.

The failure was” egregious and inexcusable”, Mr Johnson told the BBC”. Because they are busy and the law allows them to do so, judges kept kicking the case down the road as they frequently do in response to retrial petitions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHideko claims that the forced confession and the abuse her brother endured were at the heart of the injustice.

However, according to Mr. Johnson, there are no false accusations that result from a single error. Instead, they are compounded by failings at all levels- from the police right through to the prosecutors, courts and parliament.

” Judges have the last word, “he added”. When a wrongful conviction occurs, it is, in the end, because they said so. All too often, the responsibility of judges for producing and maintaining wrongful convictions gets neglected, elided, and ignored.”

Against that backdrop, Mr Hakamata’s acquittal was a watershed- a rare moment of retrospective justice.

The judge presiding over his retrial apologized to Hideko for how long it took to bring justice after declaring Mr. Hakamata innocent.

A short while later, Takayoshi Tsuda, chief of Shizuoka police, visited her home and bowed in front of both brother and sister.

” For the past 58 years … we caused you indescribable anxiety and burden,” Mr Tsuda said”. We are truly sorry.”

The police chief received an unanticipated response from Hideko.

” We believe that everything that happened was our destiny,” she said”. We won’t be complaining right now.

The pink door

After nearly 60 years of suffering and anxiety, Hideko has decided to style her house with the sole intention of letting some light in. The rooms are bright and inviting, filled with pictures of her and Iwao alongside family friends and supporters.

Hideko laughs as she shares memories of her” cute “little brother as a baby, leafing through black-and-white family photos.

The youngest of six siblings, he seems to always be standing next to her.

” We were always together when we were children,” she explains”. I was always aware that my younger brother needed my care. And so, it continues.”

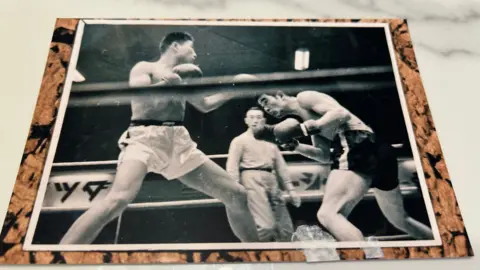

She introduces Mr. Hakamata’s ginger cat, which he typically occupies in the chair, when she enters his room. She then points to images of him as a young boxing pro.

” He wanted to become a champion,” she says”. Then the incident happened.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter Mr Hakamata was released in 2014, Hideko wanted to make the apartment as bright as possible, she explains. So she painted the front door pink.

I firmly believed that if he lived in a bright room and lived a cheerful life, he would naturally recover.

It’s the first thing one notices when visiting Hideko’s apartment, this bright pink statement of hope and resilience.

It’s not clear whether it has succeeded because Mr. Hakamata continues to chatter for hours, much like he did for years in a jail cell the size of three single tatami mats.

However, Hideko won’t go on to explain what their lives might have looked like if it weren’t for such a horrible miscarriage of justice.

When asked who she blames for her brother’s suffering, she replies:” no-one”.

” Complaining about what happened will get us nowhere.”

Her priority now is to keep her brother comfortable. She shaves his face, massages his head, slices apples and apricots for his breakfast each morning.

Hideko, who has spent the majority of her 91 years fighting for her brother’s freedom, says this was their fate.

” I don’t want to think about the past. I don’t know how long I’m going to live,” she says”. I simply want Iwao to lead a peaceful and tranquil life.

Additional reporting by Chika Nakayama