BBC

BBCFrom his chair, Michael Northey watches slowly over his father’s grave, and lays a rose for the very first day.

” This is the closest I’ve been to him in 70 years, which is ridiculous”, he jokes painfully.

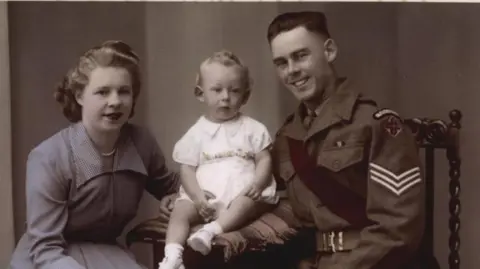

Born into a bad home in the alleys of Portsmouth, Michael was also a child when his parents, the youngest of 13 children, left to fight in the Korean War. His brain was not identified, and he was killed in action.

For generations, it lay in an unmarked grave in the UN tomb in Busan, on Korea’s west coast, adorned with the monument ‘ Member of the British Army, known unto God’.

Then it bears his brand– Sergeant D. Northey, died 24 April 1951, time 23.

Lieutenant Northey, along with three people, are the first unknown American troops killed in the Korean War to be properly identified, and Michael is attending a meeting, along with the other families, to name their graves.

Michael had spent years looking up his father’s location after failing to find out until he was finally done.

” I’m ill and do n’t have a lot of time left myself, so I’d written it off, I thought I’d never find out”, he says.

However, Michael received a visit a few months ago. He was unaware that the Ministry of Defense experts were conducting their personal investigation. He claims he “wailed like a ghost for 20 minutes” after learning the media.

” I ca n’t describe the emotional release”, he says smiling. ” This had haunted me for 70 years. I had a bad feeling for the weak woman who called me.

Michael Northey

Michael NortheyThe person who answered the phone was Nicola Nash, a criminal researcher at the Gloucester Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre, who typically assists in identifying First and Second World War victims.

She had to compile a list of the 300 American troops who were still missing, of which 76 were interred in the Busan tomb, so she had to start from scratch.

Only one man was buried in Gloucester Regiment with commander stripes, as well as one key, according to Nicola who examined their burial records.

Lieutenant Northey and Major Patrick Angier were identified by Ms. Nash after searching the regional archives and referencing eyewitness accounts, household letters, and battle office reports.

Both were killed in the famous Battle of the Imjin River in April 1951 when the Chinese Army, which had joined the conflict on the North Vietnamese area, attempted to push the allies down the peninsula to recapture Seoul as the country’s capital. The men maintained their position for three weeks, allowing their fellowcomrades to retreat and properly defend the city, despite being vastly outnumbered.

The issue at the time, Ms Nash explains, is that because the war was so terrible, most of the people were either killed or captured, leaving no one to determine them. Their puppy keywords had been taken out and scattered by the opponent. No one had thought to go back and bit the pieces together until the prisoners of war’s records were made public until they were freed.

For Ms Nash, this has been a six-year “labour of love”, made somewhat easier, she admits, by having some of the people’s kids still alive to bring about, something that has even made the process more specific.

The children have spent their entire lives without any knowledge of what happened to their fathers, and it means everything for me to be able to send them to their graves, say goodbyes, and find them closing, she says.

The people are seated on chairs during the festival to honor the Korean War’s countless foreign soldiers who died and fought in the war. They are accompanied by veterans from their former troops.

Major Angier’s child Tabby, then 77, and his nephew Guy, stand to learn snippets of letters he wrote from the front. In one of his last names, he tells his partner:” Lots of love to our lovely children. Show them how many Daddy misses them and may return when he is finished working.

At the time her father left for the combat, Tabby was three, and her thoughts of him are tense. She says,” I can recall someone standing in a room with canvas bags that had to have been his equipment for Korea, but I ca n’t see his face.”

At the time of her father’s death, people did n’t like to talk about wars, Tabby says. Instead, those in her little Gloucestershire town used to note:” Oh, those poor kids, they’ve lost their parents”.

” I used to think that if he’s lost, they’re going to get him”, Tabby says.

But as the centuries passed and she learnt what had happened, Tabby was told her husband’s brain would never be found. On the field, it was last discovered that it had been abandoned underneath an inverted vessel.

Tabby has twice been to this tomb in an effort to get as near to her father as she could, despite never realizing he was there from the beginning. ” I think it will take some time to fall in”, she says, from his recently adorned grave.

The impact has been even greater for 25-year-old Cameron Adair from Scunthorpe, whose great, great uncle, Corporal William Adair, is one of two men from the Royal Ulster Rifles Ms Nash has even managed to identify. Infantryman Mark Foster from County Durham is the other.

In January 1951, a flood of Chinese soldiers forced both people to flee, killing them both. Corporal Adair did not have children, and when his wife died but did his remembrance, leaving Cameron and his family aware of his life.

Cameron “has a true sense of pride” because finding out his comparative “helped bring flexibility to so many people,” he claims. ” Seeing this firsthand has actually brought it home,” said one witness.

Cameron, who is now the same time as his brother when he was killed, is inspired and declares his desire to serve wherever the need arises.

In the hope that she can bring the peace and joy Cameron, Tabby, and Michael have experienced, Ms. Nash is currently gathering DNA from the family of the other 300 lost soldiers.

” If there are still American workers missing, we will preserve trying to find them”, she says.