BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson‘ Thomas’- no his real title- was 13 years older when he began his second stint in prison.

Following the sudden death of his father, he had robbed a shop in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT ). He was detained for a fortnight but, within a fortnight, he was up in prison for another crime.

The Indian student has spent much more of his or her time in prison than at home, almost five years later.

” It’s hard changing”, Thomas tells me. ” ]Breaking the law ] is something that you grow up your whole life doing- it’s hard to]stop ] the habit”.

In the Northern Territory, his narrative is not unique; it revolves around violence, arrest, and discharge.

Over time, crimes become more significant, sentences are lengthened, and prison breaks are always shorter for many.

The Northern Territory is the part of Australia with the highest rate of incarceration: more than 1,100 per 100,000 people are behind bars, which is greater than five times the national average.

Additionally, it is more than half as prevalent in the US, which has the highest number of prisoners.

However, the issue of jailing children has come into focus here after the state’s new government dubiously reduced the legal responsibility age from 12 to 10 years old.

The move, which defies a UN advice, means probably locking up yet more younger people.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon AtkinsonIt’s not just an issue of confinement. It’s one of inequalities to.

While around 30 % of the Northern Territory’s community is Indian, almost all fresh persons locked up these are Indigenous.

Thus, the new regulations are largely affecting Indian areas the most.

After campaigning to protect Territorians, the Country Liberal Party ( CLP ) government now claims to have a mandate. It helped the party state a landslide defeat in August’s elections.

Sunil Kumar voted for the Cpo among others.

He’s the owner of two American restaurants in Darwin, and he wants politicians to get more drastic actions. He’s been the victim of five or six burglaries this year.

” It’s young kids doing]it ] most of the time -]they ] think it’s fun”, explains Mr Kumar.

He claims to have changed the locks, installed monitors, and even offered kids outside with free drinks in an effort to entice them.

” How come they are out and families do n’t know”? he says. ” There should be a sentence for the kids”.

Critics claim that the political rhetoric about violence has little to do with actual numbers, despite its potent impact.

Since Covid, children offenders have increased. Last year, there was a 4 % rise nationwide.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the levels in the Northern Territory are only about half of what they were 15 years ago.

Officials, though, are playing to people ‘ concerns.

As well as lowering the age of legal duty, they have also introduced tougher bail policy known as Declan’s Law, after Declan Laverty, a 20-year-old who was fatally stabbed last year by people on parole for a prior alleged abuse.

His family Samara Laverty remarked,” I always want another family to go through what we have.”

” The departure of this policy is a turning place for the Territory, which will become a safer, happier, and more peaceful area”.

” Ten-year-olds still have baby teeth”

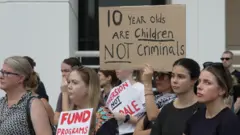

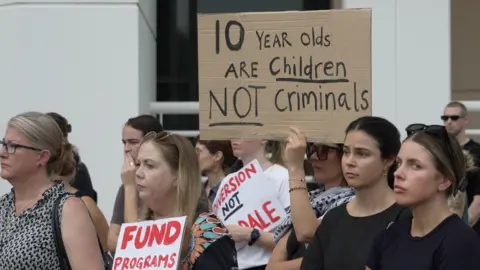

A smaller group of protesters gathered outside parliament last month to start the political debate over the rules in Darwin.

One lady held up a sign that read: ‘ 10 year olds still have child teeth’. Another asked: ‘ What if it was your baby?’

” Our young folks in Don Dale need to have option for hope”, said Indian father, Aunty Barb Nasir, addressing the protesters.

She was referring to a well-known youth detention facility only outside Darwin, where abuse was documented in Australia and led to a royal payment investigation.

They are lost in the place, Aunty Barb said, so we must generally have up for them.

Kat McNamara, an independent legislator who opposed the bill, told the masses:” The idea that in order to help a 10-year-old you have to criminalise them is absurd, inefficient and socially bankrupt”.

After a wave of applause, she added:” We are not going to have for it”.

But with a huge majority in parliament, the CLP quickly managed to pass the rules.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon AtkinsonThe legislation passed simply last year that had recently raised the legal responsibility threshold to 12 unfastened.

With the exception of the Australian Capital Territory, the time is currently 10 across the nation, up from 10 to 14 while another Australian states and territories have been under stress to raise it.

Australia is not alone – in England and Wales, for example, it is also set at 10.

But in contrast, the majority of European Union people make it 14, in line with UN tips.

The Northern Territory’s Chief Minister, Lia Finocchiaro, argues that by lowering the age of legal duty, government is “intervene early and address the root causes of murder”.

She said next month,” We have this commitment to the child who has been let down over a number of ways over a long period of time.”

” And we have ]an obligation to ] the people who just want to be safe, people who do n’t want to live in fear any more”.

But for people like Thomas, now 18, prison did n’t fix anything. His acts only got worse, and his day inside increased.

He says he finds jail curiously comforting. It’s not that he likes it, but with captivity comes experience.

” Most of my family has spent time behind bars.” Because of the treatment provided by all the boys, I felt at home.

Related cycles exist for his two younger brothers, who are also in it. Their mother once took a bus to visit all three of their prisonmates each year.

Although Thomas has been free for almost three weeks since he was a girl, he still has an ankle bracelet that has been issued by the authorities.

Brother 2 Another, an Aboriginal-led initiative that coaches and supports First Governments children who are incarcerated in the justice system, has helped him.

BBC/Simon Atkinson

BBC/Simon Atkinson” Locking these boys away is just a reactive approach to go about it”, says Darren Damaso, a youth chief for Brother 2 Another.

” There needs to be more remedial help services, more financing towards Aboriginal-led programs, because they truly understand what’s happening for these families. Finally, gradually, will we begin to notice change. But if it’s only a ‘ lock them up ‘ definition behavior, it’s not going to work”.

Mr. Damaso has ties to the Yanuwa and Malak Malak people, and he is a member of the Larrakia Aboriginal folks, who are the region’s ancient owners.

His organization provides a place for relaxation, a visual area, and a gym to young people who visit a renovated unit on a former industrial estate on the outskirts of Darwin.

Brother 2 Another also works in schools and tries to assist younger people in finding employment, which is a challenge for many police and prison personnel.

” It’s a self-perpetuating routine”, says John Lawrence, a British criminal attorney who’s been based in Darwin for more than three decades.

He has argued that to avoid prison in the first place, more cash needs to go into education than the prison system.

Tribal citizens “have no words, and so they suffer excellent injustice and harm”, says Mr Lawrence.

” This can happen, which shows how prejudiced this country is, is very vividly and naturally.”

A nationwide conversation

The Northern Territory’s politics do n’t focus solely on crime.

In Queensland’s new votes, the winning strategy by the Liberal National Party played heavily on its tagline:” Child violence, child time”.

In a new report by the Asian Human Rights Commission, Anne Hollonds, the National Children’s Commissioner, argued that by criminalising vulnerable kids- many of them First Nations children- the land is creating “one of Australia’s most serious human rights challenges”.

” The systems that are meant to help them, including health, education and social services, are not fit-for-purpose and these children are falling through the gaps”, she said.

The evidence indicates that locking up children does not make the community safer, and we cannot control how we can solve this problem.

Which is why there’s a growing push to fund early intervention through education, not incarceration, and trying to reduce marginalisation and disadvantage in the first place.

” What are the cultural strengths of people? What are people’s strengths as a community? We are building on that”, says Erin Reilly, a regional director for Children’s Ground.

Her organization collaborates with communities and schools on their ancestral lands, teaching them about indigenous foods and remedies, as well as about the Aboriginal “kinship” system, which explains how people integrate with their communities and their families.

According to Ms. Reilly,” We work in a way that works for Aboriginal people and aligns Indigenous world views and values.”

We are aware that our society’s health and educational systems are dysfunctional.

For Thomas, life on the inside was hard, involving weeks at a time spent in isolation. But on the outside, he says, there’s little understanding of the circumstances he’s lived through.

” I felt like no one cared. Nobody wanted to listen”, he says.

He mentions the bite marks on his forearms and says,” See the scars here, I hurt myself all the time”?

Additional reporting by Simon Atkinson