AFP

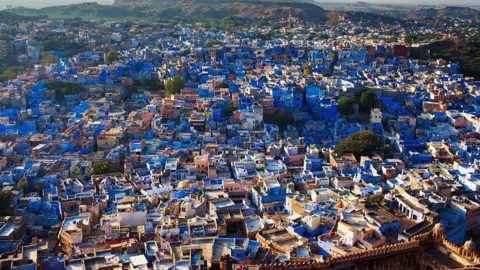

AFPThe town of Brahmapuri in Jodhpur area, India, is situated at the feet of a famous fort that is perched atop a hill.

Built in 1459 by the Rajput prince Rao Jodha- after whom the city is named- the gated, guarded settlement came up in the Mehrangarh Fort’s shadow, and was finally recognised as the old or unique city of Jodhpur, with azure-coloured homes.

Esther Christine Schmidt, assistant professor at Jindal School of Art and Architecture, says that the iconic blue colour likely was n’t adopted before the 17th Century.

But since then, the city’s blue-coloured homes have become a different symbol of Jodhpur’s identification and garnered attention from around the globe.

In reality, Jodhpur, in Rajasthan condition, is called the’ Blue City ‘ because Brahmapuri remains its spirit, despite developments over the last 70 times, explains Sunayana Rathore, the director of the Mehrangarh Museum.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Sanskrit, Brahmapuri was established as a settlement of upper-caste families who adopted the color orange as a sign of their social devotion in the Hindu class system.

They set themselves off, much like the Jews of Chefchaouen- or the blue area of Morocco- who settled in the older part of town known as Medina, in the 15th Century, while fleeing the Colonial Inquisition. According to legend, they painted their homes, mosques, and even public buildings with the color blue, which is revered as a holy hue in Judaism and represents the divine skies.

Finally, the color proved to be beneficial in more ways than one. The orange color mixed with stone cement- also used in the homes of Brahmapuri- cooled the interiors of the structures, besides bringing in tourists drawn by the neighbourhood’s dramatic look.

But unlike in Chefchaouen, the violet colour in Jodhpur has begun to dissipate. There are several causes of this.

Because of the nearby abundance of natural purple, the town of Bayana in eastern Rajasthan was one of the main indigo-producing regions in the region, blue was previously a practical choice for the residents of Brahmapuri. However, indigo lost popularity over time because growing the grain exaggeratedly damaged the earth.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaAdditionally, the conditions have increased so much that the orange paint in homes is insufficient to keep them cool. A rise in disposable incomes has even resulted in a gradual transition to more contemporary features, such as air conditioners, to help people deal with the scorching heat.

Udit Bhatia, an assistant professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology ( IIT ), Gandhinagar, works on resilience infrastructure and the effects of climatic extremes on built and natural systems.” Temperatures have risen gradually over the years.

According to a pattern research conducted by IIT Gandhinagar, the average temperatures in Jodhpur increased from 37.5C in the 1950s to 38.5C by 2016.

Mr. Bhatia claims that the ink had pest-repelling properties as a result of mixing natural purple with bright blue copper sulphate, a well-known antifouling agent used in colors from the 20th Century.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaMr. Bhatia points out that urbanization can lead to the unscientific abandonment of traditions that were intended to support systems and ecologies, even though he does n’t believe it to be evil.

Even the lightest breeze, he claims, may make them feel hotter than they did yesterday if they were walking down an alley in Jodhpur with violet properties on either side.

The heat island effect occurs when the heat and sunlight are amplified and reflected back into the atmosphere through the concrete, asphalt, and glasses used to construct structures, known as the warmth island effect. With darker paints, the impact is magnified further.

Additionally, as cities are increasingly welcoming new cultures and people, traditional methods of construction, such as using lime plaster in hotter climates, are being replaced by more advanced methods, such as using cement or concrete, which do not well absorb the blue pigment.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAditya Dave, a 29-year-old civil engineer from Brahmapuri, says that his 300-year-old family home has held on to blue for the most part, though, occasionally, they repaint the outer walls in other colours now.

This is primarily because of recent years ‘ increase in costs caused by the indigo’s scarcity. Repainting houses blue would cost around 5, 000 rupees ($ 60, £45 ) up until a decade ago, while today, it would be more than 30, 000 rupees.

According to Mr. Dave,” Today, there are also open drains lining homes,” which “dirts the blue paint and damages the walls”

That’s why, when he built his own home in Brahmapuri five years ago, he chose a tile facade that is n’t in need of frequent renovations.

” It’s simply more cost-effective that way”, he says.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaAccording to Deepak Soni, a clothing seller who collaborates with local authorities to preserve the color’s already vibrant homes in Brahmapuri and restore those that have lost the hue, visitors are left feeling cheated by this change.

We should be embarrassed that when someone searches for the homes that made up our city’s identity, they do n’t discover them. So many foreigners compare Jodhpur to Chefchaouen. If Chefchaouen has managed to keep their homes blue for centuries, why ca n’t we”? he asks.

Mr. Soni, who was originally a resident of Brahmapuri and who now lives outside the walls of Jodhpur, forged agreements with local authorities and communities to protect the distinctive heritage of their hometown in 2018. He has also raised money locally since 2019 to pay for 500 Brahmapuri residents to have their homes ‘ exteriors painted blue each year.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaHe has persuaded nearly 3, 000 Brahmapuri homeowners to switch out their homes ‘ exteriors and roofs,” so that at least when someone takes a picture there, the background appears blue,” he claims. Over the years, he has persuaded nearly 3, 000 homeowners.

According to Mr. Soni, about half of the roughly 33, 000 homes in Brahmapuri are currently blue.

He is collaborating with local authorities and lawmakers to create a lime plaster project to allow the color to be applied to more homes.

It’s the least he can do for the city he calls home, he says.

Why would people from outside Jodhpur care about our city if we did n’t care about its history and worked to save it?

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook