Getty Images

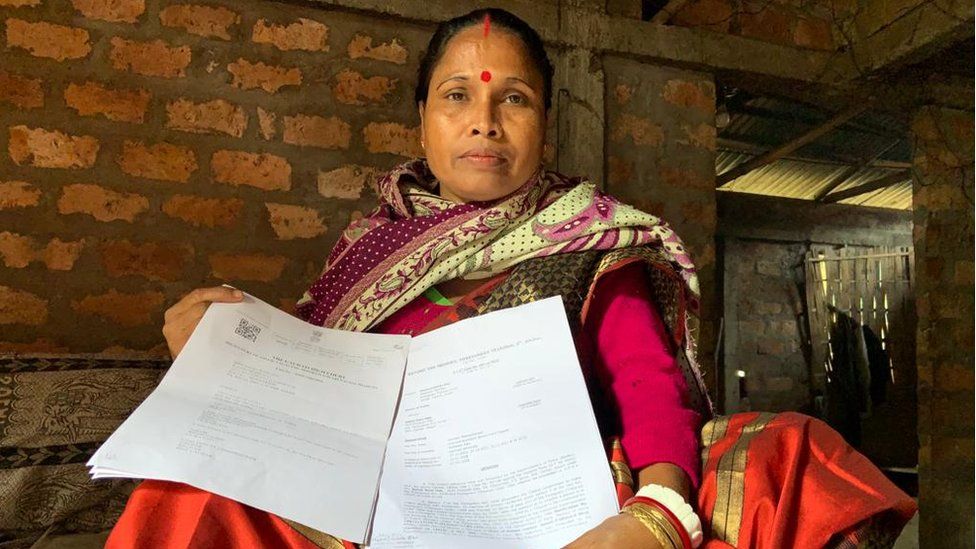

Getty Images Ila Popat has been living in India for more than five decades.

She did marry here, had children, obtained an Indian native driving licence as well as a voter identity card.

But the girl still can’t take a trip abroad as an Indian because she doesn’t have a passport, effectively making her stateless.

She has now contacted the Bombay Higher Court to immediate Indian officials in order to issue her a passport.

Mrs Popat, 66, was born in Uganda in 1955 and came to Indian by ship as a 10 year old on her behalf mother’s passport.

She has since lived in the nation and has made it her home, with various documents to verify her “Indian-ness” since she calls this.

She is in this distinctive situation because her decades-long attempt to acquire a passport has observed her labelled “stateless” by three various countries.

“Each time, they would get stuck at the question of my citizenship, inch she says.

Mrs Popat’s father was born and raised within Porbandar, a port city in the western Indian state of Gujarat.

In 1952, he left to work in Uganda and a few years later acquired a British passport.

Mrs Popat was born in Kamuli city of the east Africa country in 1955, seven years before the country’s independence through British rule.

In 1966, she still left for India along with her mother plus her younger sibling as Uganda had a period of extreme political turmoil which would lead to the suspension system of its constitution as well as a state of crisis.

“I came to India as a minor, with my name signed up on my single mother’s passport. Her passport stated she was a British Protected Person , ” Mrs Popat says. This was the class of nationality given by the UK federal government.

Her lawyer Aditya Chitale explains how she entered Indian without a passport during the time.

“Presumably the rules after that said that a child can enter the country on their parent’s passport, or even she would never have been allowed entry, inch he says.

In India, Mrs Popat’s family first lived in Porbandar but relocated to Mumbai in 1972. This is where Mrs Popat got married in 1977 and raised her family.

In 1997, Mrs Popat applied for Indian citizenship, having fulfilled the circumstances under India’s 1955 Nationality Act which included marriage to a citizen and residency of seven yrs. But her program was not “viewed favourably” and rejected.

Getty Images

She after that approached the Uk High Commission within Mumbai since each her parents had held British given. Her mother still had family in the united kingdom.

The High Commission, nevertheless , said she had not been eligible to apply for a British passport since none her father nor her paternal grandfather were “born, authorized or naturalised” in the land or its colonies after 1962.

Additionally, it said Mrs Popat was likely to be an Ugandan citizen “but if the Ugandan professionals refuse passport facilities you would appear to be a stateless person. inch

This would be the first of the number of occasions she’d hear herself classed this way.

In the following decades, she requested an Indian passport twice, getting turned down by authorities every time.

“I would inquire if I could a minimum of get a travel passport to visit my grandpa in the UK, but I couldn’t get one, inch she says.

The girl younger brother, who have lives in Vadodara, a new British passport like their parents.

How did she slip through the cracks and the girl parents didn’t obtain her a British passport?

“We resided in a joint household. We didn’t know much and went by what the elders mentioned. There was no issue of asking for more information, so we didn’t understand what mistakes had been produced, ” she says.

It was only when her third application was rejected in 2015, Indian authorities told her that she should first register as being a citizen of the country.

Mr Chitale wants. “She should’ve requested citizenship first with no which she can’t get a passport, inch he says.

Mrs Popat says she was not guided properly.

“We didn’t know a lot, and no-one informed us what to do. We might just go in and out of numerous government offices looking for a way. Everywhere, individuals would just call me ‘stateless’ plus treat my case as hopeless. ”

In 2018, her daughter wrote towards the Ugandan High Payment in Delhi meant for citizenship or passport on the basis of which Mrs Popat could make an application for an Indian one particular. The consulate confirmed that she was born in the country but mentioned she had “never been an Ugandan”.

Getty Images

The lady was once again inquired to apply for citizenship within India “as a stateless person”.

Within 2019, Mrs Popat finally applied for Indian native citizenship, but the girl application was declined. The official’s order said she had been living in the country without a proper visa or even passport and, hence, did not fulfil the conditions under the 1955 Citizenship Act.

This particular left her depressed, Mrs Popat states, in her 2022 petition to the Bombay High Court. “But my husband is Indian, my children and grandchildren are Native indian. I have every other government document including a good Aadhaar (an unique ID issued for all Indian residents), and yet none of it appeared to be enough, ” the girl told the BBC.

Many Indians remaining Uganda in 1972 after the country’s dictator, Idi Amin, asked all Asians in order to leave. But most found citizenship in the UK, Europe or India.

The Bombay High Courtroom is due to take up Mrs Popat’s case within August. She says she’s already missed the weddings of two of her nephews in UK. “I’ll miss another nephew’s wedding within Dubai which is days before the court time, ” she says.

All she desires for now is to be called a citizen of the country of the girl heritage and where she has lived the majority of her adult life.

-

-

10 October 2019

-

-

-

18 December 2019

-