When the story of Ridge Alkonis first broke on 29 May 2021, it did not initially attract much attention in Japan.

The US Navy officer had killed two Japanese citizens in a car accident during a trip to Mount Fuji – the victims were an 85-year-old woman and her son-in-law, aged 54.

After pleading guilty to negligent driving, Alkonis was sentenced to three years jail in October 2021. In his defence, US Navy doctors said he had been suffering from acute mountain sickness at the time of the accident. He was transferred to US custody last December.

Alkonis, stationed at the Yokosuka naval base south of Tokyo, was just the latest American serviceman to run into legal troubles. Since the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) was inked in 1960 – enabling the deployment of US military forces in the country – there have been hundreds of criminal cases involving US military personnel.

Then on 13 January, a celebratory tweet by CNN anchor Jake Tapper – accompanied by a photo of a smiling Alkonis, 36, with his wife and three children – about “great and breaking news” jolted the Japanese public.

Tapper wrote: “This morning the US parole commission ordered the full parole and immediate release with no supervision of Navy Lt Ridge Alkonis.”

Few in Japan knew that Alkonis’ wife Brittany and his advocates had led a successful pressure campaign in the United States for his release. US President Joe Biden embraced Brittany Alkonis at the 2022 State of the Union address, while Vice-President Kamala Harris raised the case with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

Utah senator Mike Lee also actively lobbied for Alkonis, tagging Mr Kishida in multiple tweets. Upon his release, he even tweeted: “Japan owes the family – and the US – an apology.”

The online outrage in Japan was pronounced. “Why are you celebrating?” asked one.

Another wrote in response to Mr Lee’s tweet: “Did he and his family apologise (to) the families of those Japanese victims in the first place?”

Despite the public anger and some coverage in Japanese media, neither government has commented publicly on the case. Prof James D Brown of Temple University told the BBC that there is little incentive for Japanese politicians or mainstream media to amplify the case.

“To do so would be to aggravate the damage to US-Japan relations at a time when there is widespread recognition in Japan that, despite its iniquities, the alliance with the United States remains essential to Japan’s security,” he said, adding that such cases are “unquestionably damaging”.

Despite the “clear frustration” over the outcome of the Alkonis case, Jeffrey Hall of the Kanda University of International Studies added: “There is a sense of resignation among many Japanese that their powerful American allies do not treat them as equals and never will. The Alkonis incident underlines that even when parties and presidents change in the United States, this sense of inequality persists.”

An unequal relationship

The simmering resentment over the American military presence in Japan is a long-running theme that dates back to the post-World War Two military occupation of Japan. At the end of the war, the American occupiers rewrote Japan’s constitution to a pacifist one and reduced the Emperor to a symbolic figurehead.

There are roughly 54,000 US servicemen stationed at 120 bases across Japan, 32 of which are in Okinawa alone. The prefecture also hosts almost 30,000 troops, while its proximity to Taiwan makes it vital in terms of the US being able to respond to any Chinese invasion of the self-ruling island.

Nowhere in Japan is the discontent over the US military presence clearer than in Okinawa, where the American occupation only ended in 1972 – two decades after the rest of Japan. The 1970 Koza riot, in which thousands of Okinawans clashed with military police, is even commemorated in a museum.

Retiree Takashi Asato, 70, has vivid memories of life as a child in 1960s Okinawa, with fighter jets constantly flying overhead and tanks and military trucks blocking the road. “Most of the beautiful sandy beaches were for the exclusive use of the US military – no entry permitted to locals. Foreign residences were surrounded by fences and had large grassy yards for the families of US military personnel.”

Mr Asato, who often ferried US troops to bases as a bus driver, added: “There were many complicated economic and cultural relationships between Okinawans and US troops, but it was a mutually beneficial relationship.”

The anger in Okinawa

A public opinion poll conducted last year revealed that 70% of Okinawan residents feel the concentration of US bases there is “unfair”. And despite a vocal anti-base movement, which often stages protests asking for their removal, that same poll indicates that more young people are resigned to the US military presence.

However, many are concerned about the noise and environmental pollution caused by military deployments. Drunken incidents involving US servicemen are common, while sexual violence against women has also occurred. Few have forgotten the infamous 1995 incident where three servicemen raped a 12-year-old Okinawan girl, sparking months-long protests.

When such incidents occur, US bases are often temporarily shut down to prevent contact with locals, so as not to further aggravate tensions. Senior US military leaders will also meet the governor to apologise.

When asked about the Alkonis case, university student Yui Tamura, 24, told the BBC that she found Tapper’s tweet “extremely shocking”. But she shares Mr Asato’s view that the bases are “inevitable”.

She added: “However, when fighter jets fly by with such loud noise that the air shakes, and when the precious ocean is reclaimed to build new bases, I feel like the people of Okinawa are being ignored.”

Geopolitical needs

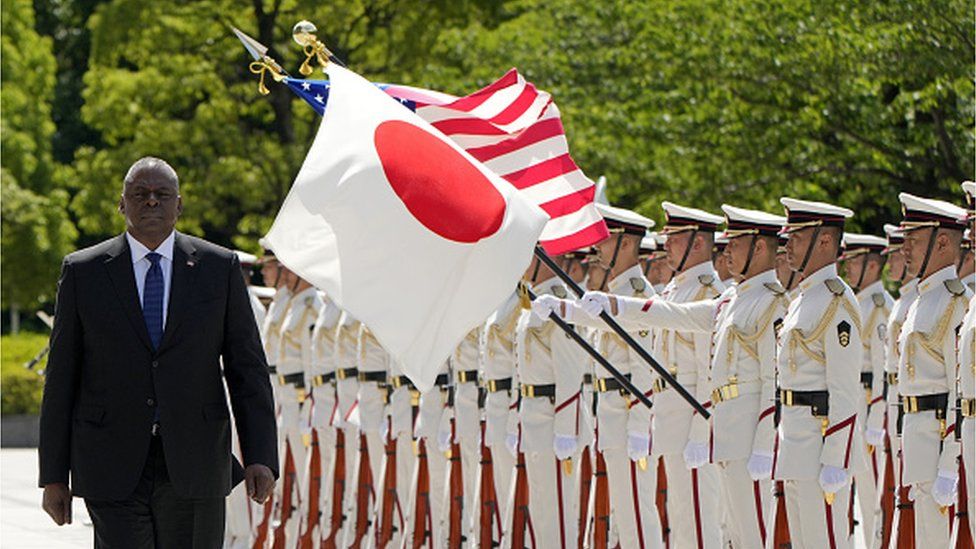

The perennial threat of North Korea, together with an increasingly assertive China and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, means the US bases are not going away. It has also resulted in what was once unthinkable: Japan’s largest military build-up since World War Two, with a two-fold increase in defence spending.

Its pacifist constitution has even been reinterpreted to allow its Self Defence Forces (SDF) to assist the forces of a foreign country in situations where either the survival and security of Japan or that of its citizens is at risk.

Notwithstanding the unhappiness of many Japanese, the US therefore remains “irreplaceable” as Japan’s core ally, said Prof Brown.

Prof Hall reckons that the US-Japan alliance is stronger than ever. “The security situation surrounding Japan is so serious that Japan’s leaders would prefer to ignore (issues like Alkonis) and keep moving forward with plans to increase military co-operation with the United States and other like-minded states. “

But Prof Brown warns that such cases may eventually take a toll. “Those opposed to the Japan-US alliance, including North Korea, China, and Russia, must be delighted whenever the United States acts with such arrogant indifference to their ally’s concerns. It’s a gift to the US’s and Japan’s adversaries.”