An American woman was battling the odds to create tools that would improve people’s understanding of the culture long before weather change became a hot topic. But many people in her native country still do n’t know Anna Mani, one of the most renowned weather scientists in the world.

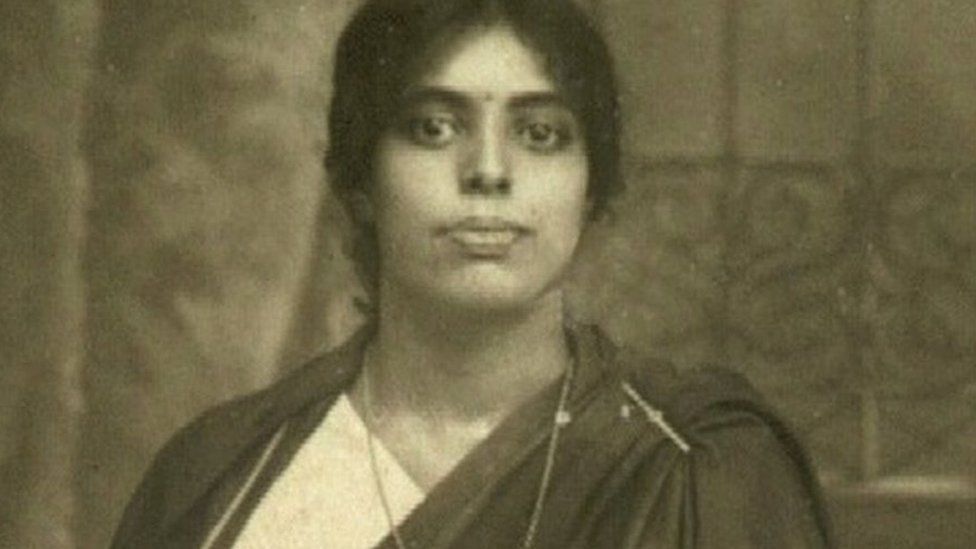

Mani, who was born in 1918 in Travancore—a former princely state that is now a part of Kerala—is best known for assisting India in creating its own weather measuring devices, thus lessening the newly independent nation’s reliance on other countries.

She did, however, also significantly contribute to professionals ‘ ability to track the ozone layer. She developed the first Indian-made ozonesonde in 1964, an instrument that is launched into the air in a balloon to measure the presence of oxygen up to 35 km ( 22 miles ) above the ground.

Mani even laid the groundwork for India to utilize alternative solutions long before it was required to do so. She set up about 150 websites to study weather energy in the 1980s and 1990s. The brave scientist traveled it with her little team to set up wind measurement stations even though some of them were in remote locations.

At a time when it was uncommon for women to pursue higher education, much less become scientists, Mani boldly followed her devotion to examine the weather. She showed a thirst for knowledge and an innate desire to travel the uncharted territory.

Mani was the sixth of eight siblings—five boys and three girls—who were born into a wealthy family. Mani reportedly asked for a set of encyclopedias instead of the diamond earrings her parents usually gave their daughters on her seventh birthday.

Mani, however, did not have an easy path to becoming a pioneer scientist. In her home, men, not women, were encouraged to pursue high-level professional careers. Her desire was to examine treatments, but since she could n’t, she made the decision to focus on science instead because she was good at it.

Before receiving a government scholarship to study abroad, she received her degree from Presidentship College in Madras ( now Chennai ) and spent the following five years researching the characteristics of diamonds at CV Raman’s laboratory at the Indian Institute of Science.

However, the fellowship was intended to study weather instruments rather than physics because India at the time required expertise in this field. Mani took advantage of the chance and took a troopship to the UK, according to Sreedharan.

She devoted the following three years to researching every aspect of wind tools, including their construction, testing, calibration, and standardization. She started working for the wind office after returning to India in 1948, a year after the nation gained its independence from British colonial rule.

She used the information she acquired it to assist India in producing its own gear, which had previously been imported from Britain and another European nations.

She established a factory where she could create more than 100 different types of devices, including ones that could measure temperature, atmospheric pressure, and rainfall. For them, she actually created thorough executive specifications, drawings, and manuals.

Another step toward Mani’s goal of investigating renewable energy sources in India was the development of instruments to measure thermal radiation and the establishment of a system of energy stations across the nation.

” Up until that point, the western countries had the monopoly on these high-precision equipment, and the majority of the design parameters were kept secret.” Therefore, according to Sreedharan, one had to start from scratch and build the overall technology themselves.

Mani achieved tremendous peaks in her job, but she also faced a lot of discrimination.

CV Raman, her illustrious coach, had a reputation for limiting the number of women he allowed into his laboratory. In an article for her book Dispersed Radiance: Caste, Gender, and Modern Science in India, Sur claims that” Raman maintained a strict detachment of women in his laboratory.”

Mani and another female student were unable to engage in healthful discussion and debate on technological ideas because they worked alone, apart from their contemporaries, for the most part.

Some of Mani’s male peers even discriminated against her. In Sur’s guide, she describes coworkers who would immediately identify even the smallest mistake a person made when handling devices or conducting an experiment as indicating “female incompetence.”

It was typically believed that Mani may be “beyond her ken” when she audited a theoretical science program, according to Sur.

Mani was unable to go on the boats to collect information when she had the opportunity to take part in the International Indian Ocean Expedition, which involved outfitting two boats with tools to examine the seasons.

Mani told the WMO in her 1991 interview,” I may have loved to have gone, but in those times women were not allowed on boats of the Indian navy.”

Mani, however, resisted the idea that she was a victim of masculine views, like many people of her generation.

She insisted that her aspirations for a career were not hindered by her sex. She told Sur,” I did not think I was either wealthy or penalized because of being female.”

Mani passed away in 2001 in Kerala’s Thiruvananthapuram capital. According to the information at hand, she always regretted getting married. Generations of people in India and abroad continue to be informed and inspired by her work and life.

Read more News stories about India here:

- The effort to save an American nurse who was being executed in Yemen

- Important component of the India Moon mission is back in Earth’s orbit.

- If China and India profit from the environment destruction fund?

- As a storm makes ashore in India, there are heavy rains.

- The American siblings are dominating the game world.

Related Subjects

On this account, more

-

-

14 November 2022

-