This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Rescuers in India have freed 41 workers who had been trapped in a collapsed Himalayan tunnel for 17 days.

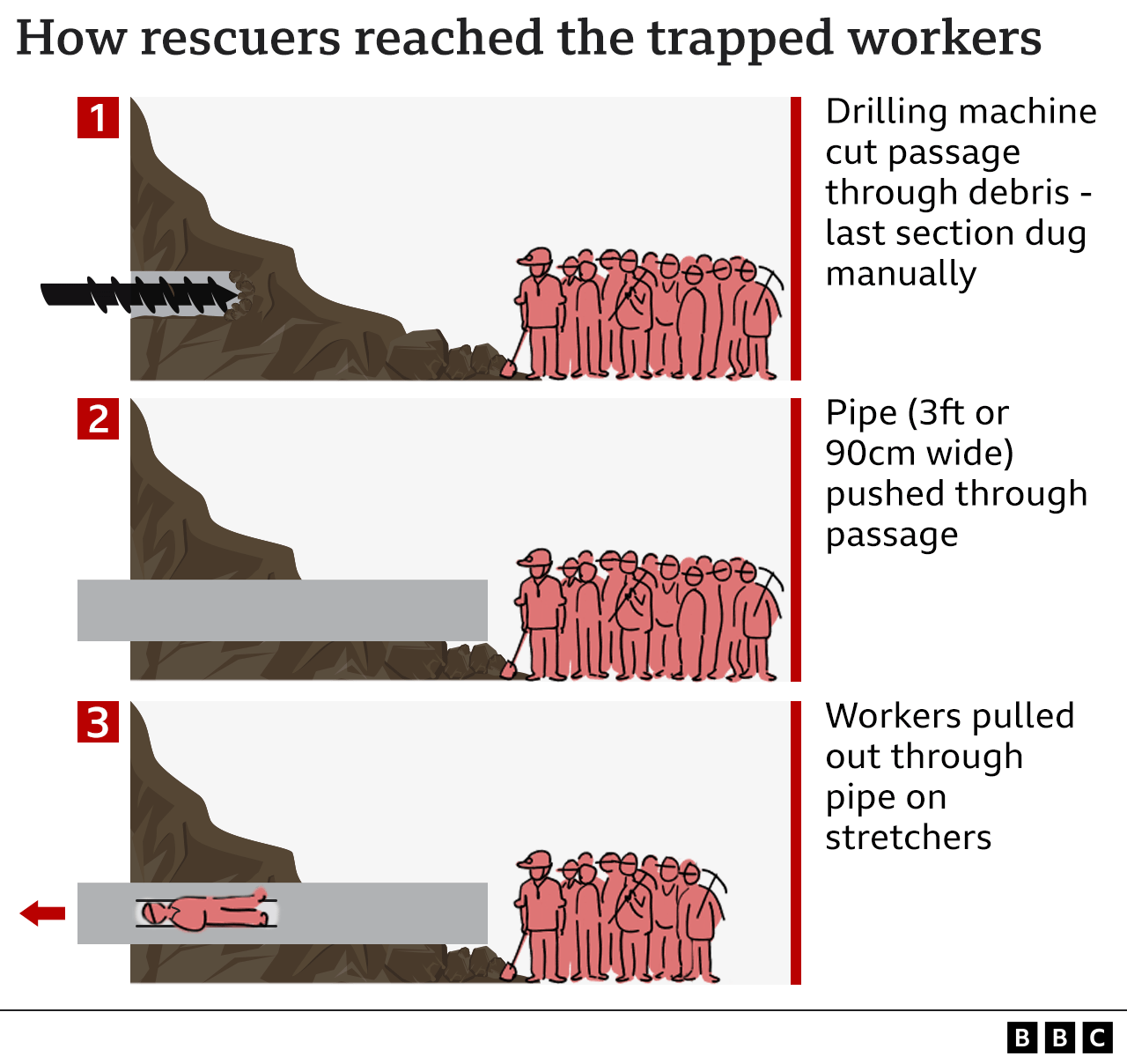

Miners drilled the final section by hand to reach the workers in the 4.5km (3-mile) tunnel in Uttarakhand.

The men, who were brought out in wheeled stretchers through a 90cm (3ft) wide pipe, were taken to hospital for check-ups. No one was injured.

Marathon efforts to free them from the Silkyara tunnel which collapsed on 12 November overcame numerous setbacks.

The mission was ultimately completed on Tuesday evening thanks to the efforts of a group of “rat-hole” miners, who used hand-held drills to break through the rock.

India’s president Droupadi Murmu wrote on X, formerly Twitter, that she was “relieved and happy” to hear the men had been freed. She also praised the rescue effort, which she said was met with obstacles that had been “a testament of human endurance”.

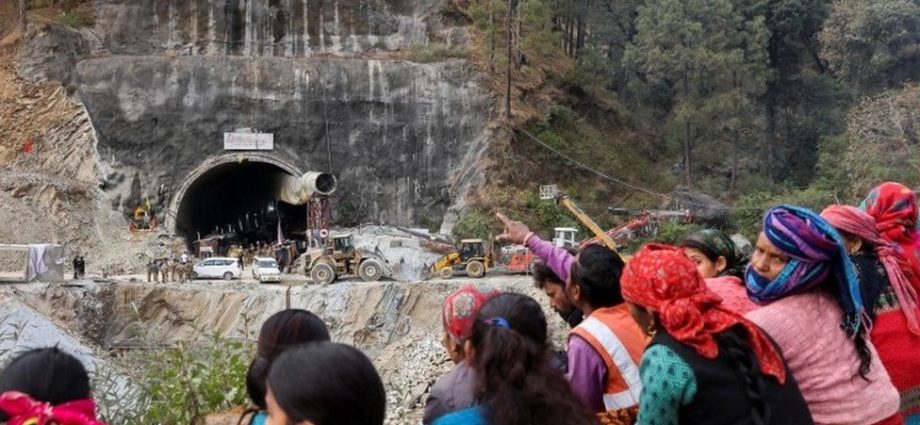

The workers were greeted with wild cheers and flower garlands as they emerged from the tunnel.

Friends, family and local residents gathered outside the tunnel, setting off firecrackers and distributing sweets.

Since early in the rescue, those above ground were able to communicate via walkie-talkies with the men, who were supplied with oxygen, food and water through a separate narrow pipe.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

The Silkyara tunnel is part of the $1.5bn (£1.19bn), 890km-long flagship Char Dham project connecting key Hindu pilgrim sites via two-lane roads in the Himalayas.

Since a landslide caused a portion of the tunnel to cave in, teams have tried to clear about 60 metres of rubble – made up of rock and metal – which lay between the men and the tunnel mouth. The aim was to create a horizontal exit passage with crawl-out pipes for the trapped workers.

Having to cut through metal rods in the rubble repeatedly impeded the rescue efforts, and loose soil slowed progress. Last Friday, officials said the workers would be out in a matter of hours – until the complete breakdown of the main drilling machine inside the tunnel.

When that happened, two dozen “rat-hole” miners were deployed to manually drill and clear the passage to the trapped workers. Trained in narrow tunnel navigation, they used handheld tools for excavation to clear the last few metres of debris to get to the workers, who came from some of India’s poorest states.

Rescue workers equipped with ropes, ladders and stretchers then entered the tunnel, with 41 ambulances positioned outside to transport the men to a hospital some 30km away.

Rescuers had also begun drilling vertically from the top of the mountain under which the men were trapped to bore an alternate rescue passage.

One of the rescuers told the BBC that “the moment we broke through the last part of the debris, there was an outburst of happiness inside the tunnel”.

“The trapped men started clapping and shouting in excitement. Then the officials asked them to keep calm, be patient. They told them: we will get you out one by one.”

The Uttarakhand government put out a statement saying the rescue had been successful “thanks to both science and God”.

The men – who are mostly in their 20s – are said to be in good health. An official from the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) told news agency ANI: “Their condition is first-class and absolutely fine… just like yours or mine. There is no concern about their health.” However, they were taken to a nearby hospital for a medical assessment.

The prolonged rescue operations had India on the edge as millions of people prayed for the men rescuers.

On 21 November, the first images of the trapped men emerged as a medical endoscopy camera was pushed through a pipeline drilled into the debris. Some 12 men in helmets and construction worker jackets were captured standing in a semi-circle in the glow of tunnel lights.

Environmentalists and residents have blamed rapid construction, including the Char Dham project, for land subsidence in the region, saying this contributed to the tunnel collapse.

The Uttarakhand region, the birthplace of the Ganges and its major tributaries, sustains more than 600 million Indians with water and food. The landscape is dotted with forests, glaciers and water springs.

Crucially, India’s climate is influenced by this area, as its topsoil serves as a significant carbon sink – naturally absorbing and storing carbon dioxide to mitigate the impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

There are two main road tunnels in the projec – the Silkyara tunnel and a shorter 400-metre tunnel in Chamba – as well as planned tunnels for railways and hydropower projects.

“There has been an intensification of tunnel work in the last 15-20 years”, Hemant Dhyani, an environmentalist, told the BBC. “These mountains are not built for such massive building of infrastructure.”