Six months after they were stripped, paraded naked and allegedly gang raped by a mob in north-east India, two women, whose ordeal was made public in a viral video, talk to the BBC in their first face-to-face interview. They speak about living in hiding, their fight for justice and their call for a separate administration for their community.

Warning: This article includes descriptions of sexual violence.

At first, all I see is their lowered eyes.

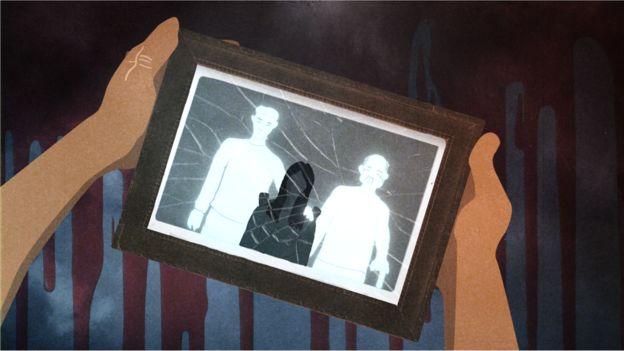

Big black masks hide Glory and Mercy’s faces and scarves cover their foreheads.

The two Kuki-Zomi women do not want to be seen. But they want to be heard.

Their ordeal was filmed and shared online. It is a disturbing watch. Less than a minute long, it shows a mob of men from the majority Meitei community in Manipur state walking around two naked women, pushing, groping them, and then dragging them into a field where they say they were gang raped.

“I was treated like an animal,” says Glory, breaking down. “It was hard enough to live with that trauma, but then two months later when the video of the attack went viral, I almost lost all hope to continue living,” she adds.

“You know how Indian society is, how they look at women after such an incident,” says Mercy. “I find it hard to face other people, even in my own community. My pride is gone. I will never be the same again.”

The video amplified their suffering but it also became evidence of injustice because it brought attention to the ethnic clashes between the Meitei and Kuki communities that broke out in Manipur in May. But while the video sparked outrage and spurred action, the spotlight made the women retreat further.

Before they were attacked, Glory was a student and Mercy filled her days taking care of her two young children, helping them with homework and going to church. But after the attack both women had to flee to a different town where they are now living in hiding.

They stay indoors now. Restricted to the walls of her temporary home, Mercy no longer goes to church or takes her children to school herself.

“I don’t think I will ever be able to live like I lived before,” she says. “I find it hard to step out of the house, I feel scared and ashamed of meeting people.”

Glory feels the same and tells me she is still “in a lot of trauma”, scared to meet people and afraid of crowds.

Counselling has helped them but the anger and hate have seeped in deep.

Six months ago, Glory was studying in a mixed class of Meitei and Kuki students in college where she had lots of friends, but now she says she never wants to see another Meitei person again.

“I will never go back to my village. I grew up there, it was my home, but living there would mean interacting with neighbouring Meiteis and I never ever want to meet them again,” she says. Mercy clenches her hands and she thumps the table as she agrees.

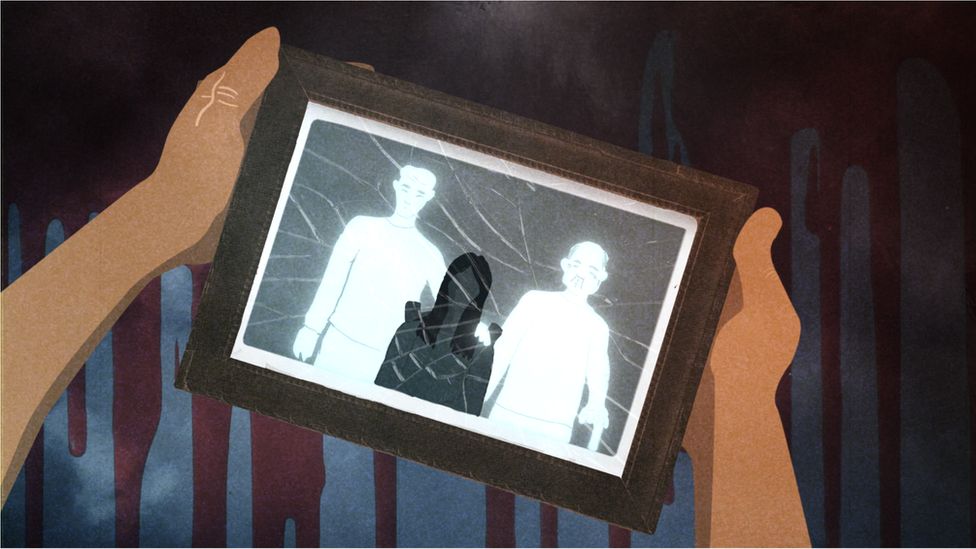

When their village was attacked and everyone ran for their life, Glory’s father and younger brother were pulled away by the mob and killed.

“I saw them die in front of my eyes,” she says softly. She describes how she had to leave their bodies in the field as she tried to defend herself.

She tells me she can’t go to look for them even now. Since the violence erupted, there is no crossover between the Meitei and Kuki-Zomi communities in Manipur. People are divided by a de facto border, lined with checkpoints manned by the police, army and volunteers from the two communities.

“I don’t even know which morgue their bodies have been kept in and I can’t go and check,” she says. “The government should hand them over to us.”

What happened in Manipur?

- More than half of Manipur’s three million people are Meiteis, while about 43% are Kukis and Nagas

- Fresh clashes flared up in May when Kukis protested against Meitei demands for tribal status – Kukis feared this would strengthen Meitei influence and let them buy land or live in Kuki areas

- The state government, led by N Biren Singh, a Meitei, has accused Kuki insurgent groups of inciting the community

- More than 200 people have died so far, mostly from the Kuki community, and thousands have been displaced from both sides

- Meitei women also say they have been attacked, and at least one police complaint was filed but, like women across India, most find it too shameful to discuss sexual violence due to the stigma attached

Mercy’s husband describes how houses and the village church were set on fire in the attack.

“I called the local police, but they said we cannot help, our police station is also under attack,” he says. “I saw a police van on the road, but they didn’t do anything either.

“I feel sad and angry at my inability to do anything. I could neither save my wife nor the villagers. That breaks my heart,” he says. “Sometimes I get very upset thinking about everything that has happened, engulfed by grief and anger, I feel like killing someone.”

Two weeks after the attack in May, he filed a complaint with the police, but no action was taken until the video surfaced in July. Police sources have told the BBC that they have now suspended the officer in charge and four others pending an inquiry.

The widespread outrage that followed the release of the video compelled Prime Minister Narendra Modi to make his first statement on the violence. That was followed by the arrest of seven men who have now been charged with gang rape and murder.

Glory, Mercy and her husband tell me they derive strength from the messages of support that have poured in since the video of the attack started circulating online.

“Without the video, no-one would have believed the truth, understood our pain,” says Mercy’s husband.

Mercy still gets nightmares and is terrified of thinking about the future, especially for her children. “It weighs me down so much, the thought that we have nothing to pass on to them, everything is gone,” she says.

They have decided to speak up to try to make sure no other woman is ever treated like this again.

Glory explains that they want a separate administration for their community. “That is the only way to live safely and peacefully,” she says.

The Kuki people have made this controversial demand many times but it is opposed by the Meitei community. The state’s chief minister has repeatedly called for a unified Manipur.

Glory and Mercy have little faith in the state government and accuse it of being biased against their community.

Chief Minister N Biren Singh did not respond when the BBC put the allegations to him, but in a recent interview with the Indian Express newspaper he said: “There’s no bias in my heart or my work.”

The video also became the moment that the Supreme Court took note of the ethnic clashes and recommended that all cases of violence be handed to independent federal investigative agencies, such as the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The top court has asked the state government to identify the bodies of people who have been killed and return them to their next of kin.

Looking to the future, Glory hopes to resume her studies at a different college so she can pursue her dream of becoming an army or police officer. “My resolve has strengthened to work for everyone in an unbiased manner,” she tells me. “And I want justice, at all costs… It’s also why I am speaking up, so no woman is harmed again the way I was.”

Mercy tells me that “as tribal women we are strong, we do not give up” and as we get up to leave, she says she has a message.

“I want to tell all mothers of all communities to teach their children, no matter what happens, never disrespect women.”

The names of the two women have been changed for this article.