At the age of 92, Lee Dae-bong doesn’t particularly enjoy getting out of bed. He has lived enough of a life. As he readjusts his pyjamas, his left hand reveals three missing fingers.

His injury is not the result of the war he fought, but the subsequent 54 years he was forced to toil in a North Korean coal mine.

The former South Korean soldier was captured during the Korean War by Chinese troops, who were fighting alongside North Korea. It was 28 June 1953; the first day of the battle of Arrowhead Hill, and less than a month before the armistice brought an end to three brutal years of fighting.

All, bar three of his platoon, were killed that day. As he and the two other survivors were loaded onto a cargo train, he assumed they were heading home to South Korea, but the train veered North, to the Aoji coal mine, where he would spend most of his life. His family was told he had been killed in combat.

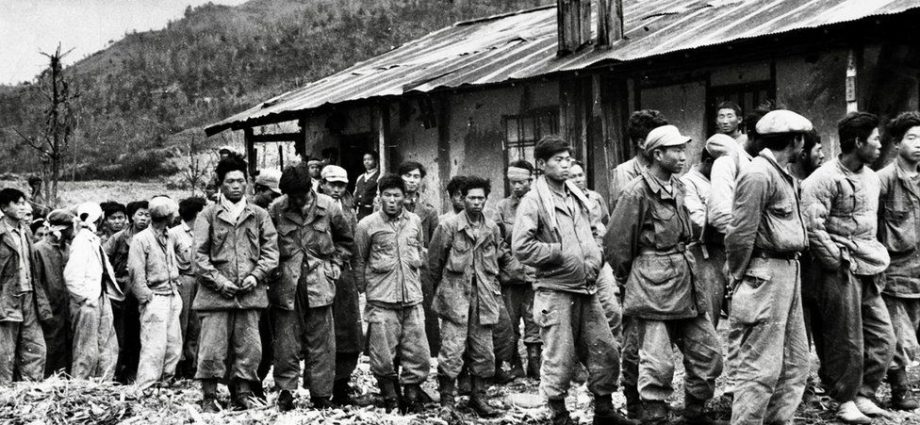

Between 50,000 and 80,000 South Korean soldiers were held captive in North Korea after the Korean War ended with an armistice agreement that divided the peninsula.

A peace treaty never followed, and the prisoners have never been returned. Mr Lee was one of the very few who managed to plot his own escape.

Over the decades, despite some skirmishes, the armistice has largely held, making this the longest ceasefire in history.

But the absence of peace has wrought havoc on Mr Lee’s life, along with his fellow prisoners and their families. As North and South Korea mark 70 years since the signing of the agreement, their stories are a reminder the Korean War is not over.

For the first years of his captivity Mr Lee was forced to work a week in the coal mine followed by a week studying North Korean ideology, until, in 1956, he and the other prisoners were stripped of their military titles and told to marry and assimilate into society.

But they, and their new families, were designated as outcasts and placed at the very bottom of North Korea’s strict social caste system.

Digging for coal, day after day, for more than 50 years was excruciating work, but it was the spectre of injury and death that Mr Lee says was the hardest to bear.

One day his hand got caught in a coal processing machine, but the loss of his fingers seemed minor, as he witnessed various friends be killed in a series of methane gas explosions.

“We gave our entire youths to that coal mine, waiting for and fearing a meaningless death at any moment,” he says. “I missed home so much, especially my family. Even animals, when they are nearing death, go back to their caves.”

As North and South Korea mark the prevailing peace on the peninsula, many of the prisoners of war and their families blame both sides for their suffering.

Various South Korean presidents have met North Korean leaders, but securing their return was low on the agenda.

The North, after releasing just 8,000 prisoners, has refused to acknowledge that any more exist.

At a summit in 2000 between the then-South Korean president, Kim Dae-jung, and the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il, the issue was not even mentioned.

This is the moment Lee Dae-bong says he lost all hope, realising the only way he would ever be coming home was if he were to escape.

Three days after his only son was killed in a mine accident, with his wife long dead, Mr Lee embarked on his journey. Now aged 77, he secretly waded across the river into China, the water up to his neck.

He is one of 80 prisoners to have escaped and made it home to South Korea, with only 13 of the escapees still alive. The remaining tens of thousands of prisoners were left to perish in the mines. Few, if any, are still alive – though their children remain.

South Korea exists today thanks to people like my father, but our suffering has still not been solved.

Chae Ah-in was six years old when her father was killed in a gas explosion at a North Korean mine. Soon her older sisters were sent to work in his place.

Still at school, she was relentlessly beaten and bullied. She could not understand why her family was cursed. Only later, when she overheard her sisters whispering, did she learn her father had been a South Korean soldier.

“For a long time I hated him,” she recounts, from her home in the outskirts of Seoul, where she arrived in 2010. “I blamed him so much for making us all suffer.”

At the age of 28, Ms Chae too chose to escape her painful existence in North Korea, crossing first into China, where she lived for 10 years. It wasn’t until she arrived in South Korea that she realised her father was a hero.

“Now I respect him and try so hard to remember him,” she says. “I feel different to other North Korean defectors, because I am the proud daughter of a South Korean war veteran.”

But Ms Chae is not recognised by the South Korean government as the daughter of a veteran who gave his life for his country.

The prisoners of war (POWs) who never made it home are marked as missing, assumed dead, and are not honoured as war heroes.

“South Korea exists today thanks to people like my father, but our suffering has still not been solved,” she says, wanting them both to be recognised for who they are.

Around 280 children of POWs have managed to escape and make it to South Korea. Another is Son Myeong-hwa, chairperson of the Korean War POW Family Association, who is fighting on their behalf.

“The children of the POWs in North Korea suffered from the pain of guilt by association, and yet here in South Korea we are not acknowledged. We want to be given the same respect that the families of other fallen veterans receive,” she said.

The South Korean government told us it is not planning to change its classification of veterans.

By the time Lee Dae-bong arrived home, already an old man, his parents and brother had died. Although South Korea had changed beyond recognition, his younger sister took him to stand on the soil of his old town.

Mr Lee recalls how his dying friends in North Korea would beg their children to one day bury them in their hometowns. Their wishes have yet to be granted. And the absence of peace between North and South Korea has left these families struggling to find peace of their own.

Both Lee Dae-bong and Chae Ah-in still dream of the North and South being reunified.

Ms Chae wants to bring her father’s body to rest in South Korea.

For North and South Korea, peace and reunification is still the officially stated goal. But 70 years since the armistice, this dream feels ever more distant.

Related Topics

-

-

28 March 2022

-