The fate of Travis King, a US soldier who crossed into North Korea, remains unknown and experts say the US is at a critical stage to try and negotiate his return home.

The challenge is America has never had an official diplomatic relationship with North Korea.

As a result, the US relies on a network of backchannels to negotiate the return of citizens detained in the country.

It is believed the 23- year-old soldier is being detained and questioned by North Korean authorities.

Private 2nd Class King was last seen a week ago running across the demilitarised zone separating North and South Korea. Tensions have since escalated in the region, with North Korea firing two ballistic missiles into the sea late Monday after a US nuclear-powered submarine was stationed in the South.

“All sides are trying to understand what happened and what to do,” said Mickey Bergman, executive director of the Richardson Center for Global Diplomacy.

Mr Bergman, who has spent nearly 20 years negotiating to return US citizens from hostile nations, said the best chance at releasing a prisoner is right after they are detained. This is when they are likely being interrogated by the country’s officials but before they have been charged with a crime, like spying.

It’s in that time before things become official that negotiators can best appeal to people’s humanity, Mr Bergman said.

“I think there’s a misconception about what negotiations are,” he said.

“If we pound our chests, and flip tables, and demand that the evil North Koreans return our soldier, we are likely going to cause them to dig in.”

Here’s how the US has previously negotiated for American citizen’s return.

The New York Channel

Because the United States has never officially held diplomatic ties with North Korea, during a detainee crisis, Sweden has served as an intermediary from their embassy in Pyongyang and has helped to relay communications to North Korean officials.

But there are also backchannels. North Korea maintains a mission at the United Nations in New York. In times of crisis, the mission – dubbed the New York Channel – has become an avenue for officials for both countries to hold talks.

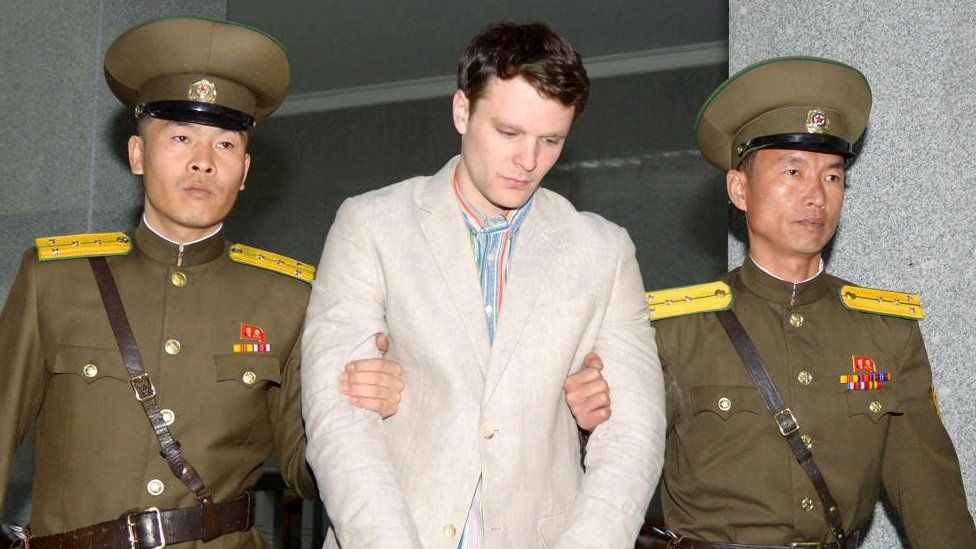

For years, Robert King was one of the first people who received a call when an American was captured by North Korea. As the former special envoy for North Korean Human Rights at the US State Department, the ambassador has helped negotiate for the release of multiple detainees including student Otto Warmbier and American missionary Kenneth Bae.

After 17 months in captivity, US college student Otto Warmbier was released from North Korean detention in 2017 in a comatose state. He returned to the United States with extensive brain damage and died days after reuniting with his family.

Otto Warmbier’s death sparked international outrage and his family has levelled allegations of abuse and torture against the North Koreans.

After a brief period of diplomacy under the Trump administration, Mr King said renewed political tensions between the two countries often colour negotiations, making detainees a pawn in wider geopolitical fights.

“[The North Koreans] see this as, ‘how do we use this opportunity to make the US look bad?’ And whatever happens it’s not going to be a happy outcome,” Mr King said.

Fringe diplomacy

For nearly 20 years, Mr Bergman has worked alongside former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson to secure the release of prisoners from countries hostile to the United States.

Although the Richardson Center is not involved in the Travis King case, Mr Bergman said in his experience, when it comes to North Korea, there isn’t a playbook for negotiations.

Instead, he said, it is best to approach tense negotiations through what he calls “fringe diplomacy”.

US non-profits and humanitarian agencies have provided aid to North Koreans for decades. When official channels stall, these non-governmental backchannels are often called upon to negotiate on behalf of a detainee’s family.

An NGO’s separation from the US government is a benefit, Mr Bergman said, because it allows negotiations to focus solely on the wellbeing and return of the detainee, instead of global politics.

“People can talk to us about policy issues but there’s nothing we can do about that,” he said. “We are much more able to insulate the issue and come up with pathways to resolve some of these situations.”

Mr Bergman said the world often focuses on the moment of “intervention,” when a political prisoner is rescued and returned home. But that moment, he said, is not possible without years of meaningful engagement.

“You have to build relationships so that when there is a crisis, you’re not starting from scratch.”

Complicating factors

But the Covid pandemic has made both of these avenues of negotiation more challenging.

North Korea completely closed its borders during the pandemic and Mr Bergman said it is unclear if the Swedish Embassy in Pyongyang has returned to full capacity.

Complicating matters further, after a brief period of attempted diplomacy, the Trump administration imposed a travel ban to North Korea, rendering US passports and visas invalid.

The ban has remained in place under the Biden administration and has effectively ended humanitarian avenues for engagement, Mr Bergman said.

“North Korea is the only country in the world where there’s a travel ban, that it’s illegal for Americans to travel,” he said. “The North Koreans see that as an insult.”

Mr Bergman, who was involved in the negotiations for Warmbier’s release, said he believes the international blowback over Otto Warmbier’s death has shifted the North Korean perspective on political detainees, and the country may be more amenable to compromise.

“After dealing with the Otto Warmbier negotiations, and the very tragic outcome, I believe that the North Koreans have chosen not play in the game of political prisoners anymore,” he said.

But whether that means US army private Travis King will have a speedy release, remains to be seen, he said.