Simply leaves from the lush green tea estates covering the hillsides of central Sri Lanka end up in cups across the world.

Tea is the island’s biggest export, normally getting more than $1bn annually, but the industry is being hard hit by the unprecedented economic crisis.

Most of Sri Lanka’s tea is grown by smaller maqui berry farmers, like Rohan Tilak Gurusinghe, who owns two acres of property close to the village associated with Kadugunnawa.

But he’s still reeling from the impact of a sudden, poorly thought-out government decision in order to ban chemical fertiliser last year.

“I’m losing money, ” he tells the BBC despondently. “Without fertiliser or fuel, Constantly even think about the future of my company. ”

The ban, ordered to try to protect the nation’s dwindling foreign reserves, was one of a number of disastrous policy decisions implemented by the now-ousted President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, with agricultural output falling significantly.

It was later turned, but fertiliser provides shot up in price and it is still difficult to source, while the government is currently unable to afford in order to import adequate supplies of petrol plus diesel.

Meant for farmers like Mr Gurusinghe, reliant on trucks transporting green tea leaves from their fields to industrial facilities for processing, it means delays which can result in the leaves drying out and reducing within quality.

“Our leaders are not troubled about providing us with the basic essentials, ” he informs the BBC.

“They’re the ones who have put us in debt: by stealing bucks and spending all of them however they want. Today, Sri Lanka is like the ship stranded in sea. ”

The huge queues of vehicles waiting around in line for gasoline aren’t just in Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo, but across the island.

General public anger at the crisis, which is also rooted within the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the island’s tourist industry, has led to the resignation of President Rajapaksa.

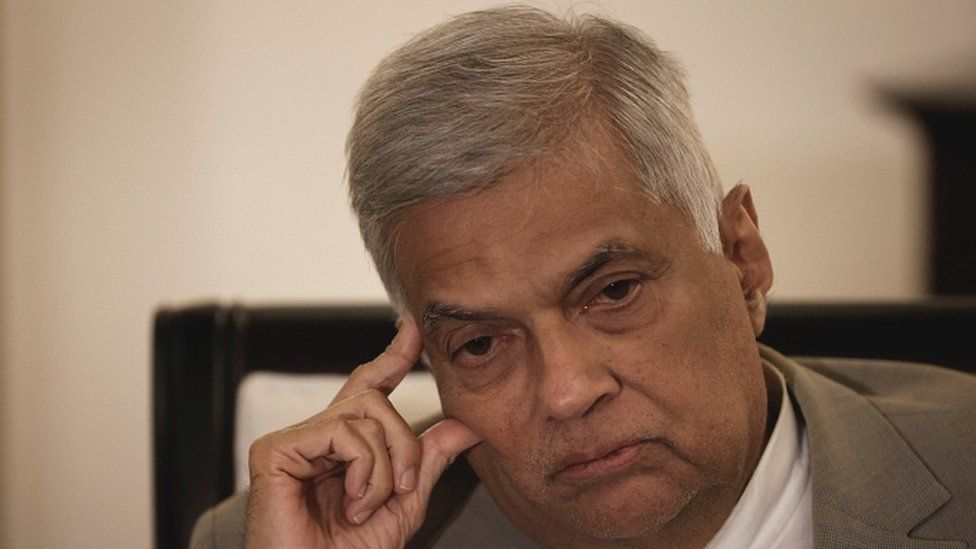

Protesters have also indicated they won’t take Ranil Wickremesinghe, the politician looking that are nominated by parliament as Mr Rajapaksa’s successor.

Mister Wickremesinghe is seen by critics as too close to the Rajapaksa dynasty. As a former six-time prime minister, this individual doesn’t represent the change demonstrators possess called for.

More political instability, however , will make resolving the particular economic crisis even more difficult.

Among teas factory owners, there is deep frustration. Teas exports are a precious source of dollars and the industry employs several two million individuals, but production ranges have dropped.

Meezan Mohideen mind a large estate and factory in Ancoombra. “Without the fuel, we are finding it very, very difficult. If this goes on, we might need to shut down all industrial facilities, ” he informed the BBC.

“Normally, about 20 lorries are operating for us. Now we have been running eight lorries. And with the power cuts, there are factories that have closed down – working three, four days a week. ”

Mr Mohideen’s factory had drastically cut down the number of times it was operating until, because of its size, this managed to source gas through a private importer.

Other, smaller sized factories are battling even more. But it is the poorest who are suffering the most in this problems.

Tea pluckers, working in the areas, picking out the sensitive tea leaves plus placing them in large sacks tied around their waists, are generally paid little more than the minimum wage.

But food costs in Sri Lanka were soaring. Inflation in June, compared with exactly the same period last year, was more than 50%.

While carrying the particular sacks of simply leaves to be weighed, near to the colonial era “line houses” where they live, green tea pluckers from Mr Mohideen’s estate complained of how much more challenging everyday life had become.

“In the past, we could get by, but now prices have more than doubled, ” says Nageshwri. “Whatever we all earn in a day, we are going to spending to eat. ”

“We don’t eat lunch any more, ” adds Panchawarni, “we eat as soon as around 10: 00, and then again in the evening. inch

The Sri Lankan government is in the sourcing more energy and is also in discussions with the International Financial Fund, but for now, whoever takes charge of the country, the hardship looks set to continue.

-

-

4 days ago

-