Australia’s controversial detention centre on Nauru is empty, after the last remaining refugee was evacuated into the night last week.

It pauses over a decade of Australia’s processing of asylum seekers on the tiny Pacific nation, with 4,183 people held there since 2012.

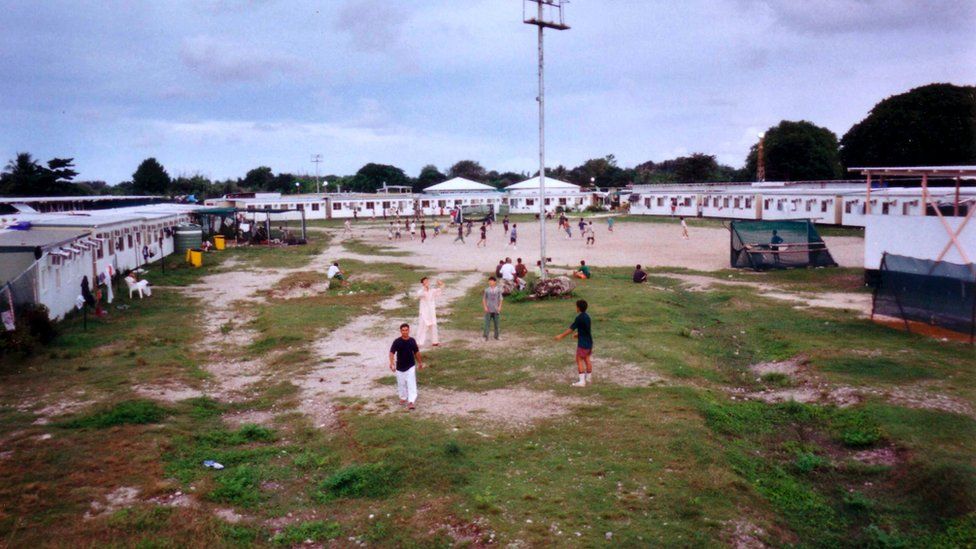

Described as a place of “indefinite despair” and “sustained abuse” by visitors from Médecins Sans Frontières and Human Rights Watch, the Nauru centre is a thorn in the side of Australia’s human rights record.

Yet offshore processing – which involves detaining people in the Pacific while they await resettlement in a third country – remains one of Australia’s most enduring policies.

Seven consecutive prime ministers have argued for its role in protecting the nation’s borders and “breaking the business model” of human traffickers.

Despite the facility sitting vacant, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s government will spend vast sums of money – including A$486m (£255m; $320m) this year – to keep Nauru open as a deterrent.

Life in ‘limbo’

Maria knows what it feels like to be airlifted off Nauru at short notice. She was evacuated to Sydney in 2014 due to a severe kidney issue, after being detained on the island for over a year.

A survivor of female genital mutilation from Somalia, Maria escaped civil war before making a weeks-long journey by plane, and then boat, to Australia.

“Just promise me: don’t die,” her younger brother had pleaded as she left the family home for the last time.

“That broke me… because we have lots of neighbours and cousins who have died in the Mediterranean,” says Maria, who does not want to give her surname.

Her time at sea felt “never ending”, Maria tells the BBC. The boat was tiny “like a kayak” and its dozens of passengers had no toilet. “I was hallucinating because I was so sick. I kept thinking about my brother. And how I didn’t want to lie to him.”

Eventually they were picked up by the Australian Navy – and ultimately transferred to Nauru.

Maria’s memories of the island are vivid and intense. She describes having cut up and burnt feet after walking on sharp stones without shoes in searing heat. The humidity left her tent covered in “green and black mould which grew on everything”, she adds.

She learnt to move in groups and ignore public sexual propositions from men within the camp. “Dehumanising” treatment, such as being watched in the shower or rationed out sanitary pads by guards, became the norm, Maria says.

“There were a lot of inappropriate relationships between the guards and the girls. You’re a refugee, but they looked at you like you were in a prison.”

After leaving Nauru, Maria was detained in Sydney, before finally being released on a bridging visa. She now runs a business in Brisbane, where she lives with her Australian husband and two children.

But her visa requires renewal every six months and she lives in terror of being taken away from her family and placed back in detention. “It’s limbo. I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

A quiet pivot

Countless refugees have shared stories of suffering like Maria’s since offshore processing began in 2001.

It was introduced by a conservative prime minister, John Howard. When he left office in 2007, the policy was suspended by Kevin Rudd’s Labor government, before being resumed – also under Labor – in 2012, initially as a stop-gap measure following a spike in boat crossings.

Successive politicians defended the policy as key to protecting Australia’s borders and saving lives at sea.

But researchers have argued it did little to curb either maritime arrivals or deaths. Both dropped from 2014 onwards, when the government quietly shifted to boat “turnbacks” – an approach that removes migrant vessels from Australian waters and sends those on board back to their countries of departure.

All new arrivals to the offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea (PNG) ceased after that pivot.

And since then, “Australia has spent considerable effort and money trying unsuccessfully to extract itself from its arrangements in Nauru and PNG,” a 2021 review of offshore detention from the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law found.

Mounting accusations of health crises among detainees prompted Australia to evacuate people from the islands under a special legislative scheme.

As a result, everyone has been taken off Nauru, but 80 people formerly detained by the government remain “trapped” in PNG, according to the Human Rights Law Centre.

Over the past decade, every expert UN body tasked with reviewing offshore processing has expressed concerns about the policy. Fourteen people have died in detention, about half through suicide.

In 2020, the International Criminal Court (ICC) called Australia’s policies unlawful and degrading but said they did not warrant prosecution.

Despite quietly shifting away from offshore processing, Australia recently signed a A$422m contract with a US prison company to oversee Nauru until at least 2025.

“The enduring capability ensures regional processing arrangements remain ready to receive and process any new unauthorised maritime arrivals, future-proofing Australia’s response to maritime people smuggling,” a spokesperson for the Department of Home Affairs said.

Mr Albanese has not commented on the last detainee leaving Nauru. His government has described its asylum seekers policies as “tough on borders, not weak on humanity”.

Critics argue offshore processing will remain a costly bipartisan policy on paper as long as “refugees are being used to try and win votes”.

“People seeking asylum by sea have been weaponised and politicised over decades in Australia,” says Jana Favero, director of advocacy at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre.

But Ms Favero and other critics believe public sentiment towards “deterrence-based” border control is shifting. She celebrates the last evacuation from Nauru as a “long overdue move for refugees” borne out of “tireless advocacy”.

“What we saw at the last election was a rejection of fear-based politics,” she says.

Polling seems to capture some shift in attitudes towards immigration. In 2017, when asked whether refugees in Nauru and PNG should be allowed to settle in Australia, 45% agreed while 48% said no, according to the Lowy Institute think tank. This year, its polling found 68% agreed that “openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation”, a 15-point increase from 2018.

Maria, who has found herself caught in the crosshairs of the government’s policy, says life for now is about co-existing with uncertainty – because so little has changed over time.

“It’s been 10 years already… at this point, I feel like I’m used to it,” she explains.

“I live my life as much as I can… but there are some days when I’m overwhelmed, and I think why me?”

Related Topics

-

-

14 April 2022

-

-

-

6 October 2021

-