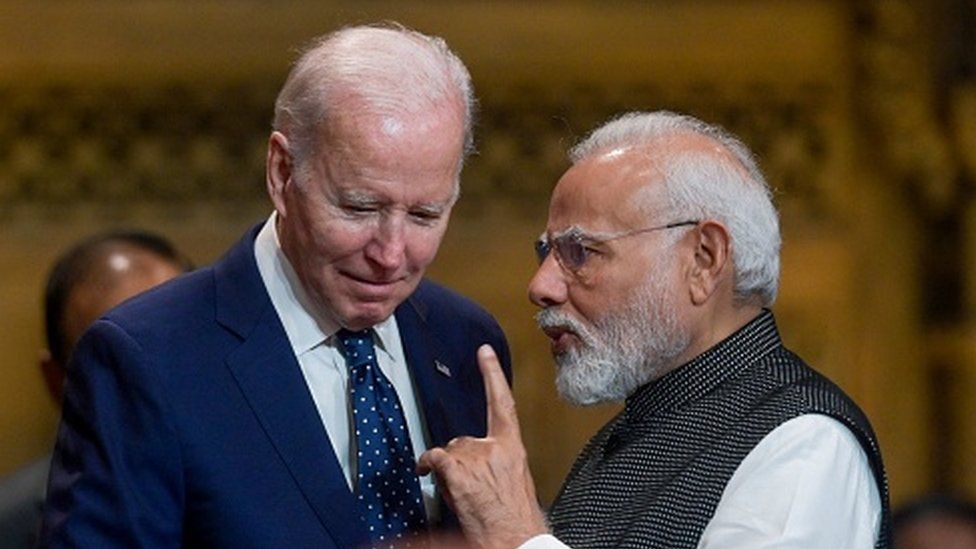

Following a lavish state visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Washington, US President Joe Biden has called his country’s partnership with India among the “most consequential in the world”. The BBC’s Vikas Pandey and Soutik Biswas explore the factors that contribute to the visit’s potential in strengthening the ties between the two nations.

The US’s relationship with India is “stronger, closer and more dynamic than any time in history”, Mr Biden said at the completion of a pomp-filled state visit by Mr Modi to the White House.

The remark may not be an exaggeration. “This summit suggests that the relationship has been transformed. It underscores just how broad and deep it has become in a relatively short time,” says Michael Kugelman of The Wilson Center, an American think-tank.

A key reason is that Washington is keen to draw India closer so that it can act as a counterbalance to China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. India-US ties had not lived up to their promise following a landmark civilian nuclear deal in 2005 because a liability law passed by India three years later hobbled purchase of reactors.

“This followed a fading commitment to the relationship during [former prime minister] Manmohan Singh’s second term as the leader of a coalition government. With Mr Modi there has been a lot more enthusiasm about embracing the US. Mr Biden has also given an overall broad directive to make it work,” says Seema Sirohi, author of Friends With Benefits: The India-US Story.

Ms Sirohi says the US put in a “lot of effort to make Mr Modi’s visit substantive and have a lot of deliverables”. Defence-industrial cooperation and technology topped the list. Consider this:

- General Electric and India’s state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics Limited joined up in a “trailblazing initiative” to make in India advanced fighter jet engines for the country’s indigenous light combat aircraft. This would mean a “greater transfer of US jet engine technology than ever before”. In other words, a clear sign that Washington not only wants to sell arms to India but is also comfortable with sharing military technology.

- India will proceed with a $3bn purchase of the battle-tested MQ-9B Predator drones from General Atomics, which will also set up a facility in India. The drones will be assembled in India to bolster the intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance of its armed forces. This fits into Mr Modi’s ‘Make in India’ campaign. The US supplies only 11% of India’s arms – Russia continues to be the biggest (45%) supplier – but hopes to become the primary provider in the coming years. “Washington’s more immediate goal is to strengthen India’s military capacity to counter China. Also, it is trying to convince Delhi that the US has the equipment and the goods to make India comfortable about starting to decouple itself militarily from Russia in the coming months and years, Mr Kugelman said.

- Mr Modi wants to make India a semiconductor base. US memory chip giant Micron Technology will invest up to $825m to build a semiconductor assembly and test facility in India. This is expected to create up to 5,000 new direct and 15,000 community jobs in five years.

- US semiconductor equipment maker Lam Research plans to train 6,000 Indian engineers to speed up India’s semiconductor education and workforce development. Also Applied Materials, the biggest maker of machines for producing semiconductors, will invest $400m to establish an engineering centre in India.

“It is all about the future now. Both sides are talking about cutting-edge technologies and how to seed and shape the future,” says Ms Sirohi.

The India-US relationship has seen many ups and downs since the US seriously began courting India – first under President Bill Clinton and then under the George Bush administration. The response from India was measured, never overeager or too forthcoming.

The reason was the way India saw geopolitics and its own place in the global order. The strategy of nonalignment, started by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, has always been deeply rooted into India’s foreign policy.

India never wanted to be seen in one camp or the other, or to be seen as junior strategic partner to a global superpower. Mr Modi has not left the ideals of what some describe as “strategic altruism” in Indian foreign policy.

But Mr Modi is leading a different kind of India, one which has considerably more economic and geopolitical heft. He has owned the India-US relations – he formed close bonds with former presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump and now with Mr Biden.

But India’s “strategic autonomy” has not been sacrificed. Washington would have wanted India to go a step further on Russia and probably take a harder public stand on China.

But the Biden administration didn’t seem disappointed as Mr Modi repeated his line that “this was not the era of war” without mentioning Russia. The Indian prime minister did speak about the importance of beefing up humanitarian assistance to Ukraine. He didn’t mention China by name either but did talk about the importance of a free and prosperous Indo-Pacific.

This is how far Mr Modi could have pushed his administration’s policy without compromising on strategic autonomy. It may not have been the ideal way for Washington but it didn’t come in the way of making Mr Modi’s visit a success.

“The two militaries are working more closely together. They now have arrangements in place where they could use each other’s facilities for refuelling and maintenance purposes. They are holding joint exercises and they’re sharing a lot more intelligence. Credit to Mr Modi for managing to really test the limits of strategic autonomy. In the sense that he is getting about as close as you can to a major power without signing on to a full-fledged alliance,” Mr Kugelman says.

India and the US have had major trade differences in recent years over tariffs. Trade relations particularly suffered during the Trump administration.

The two sides were not expected to announce anything major in trade as it was understood that the discussions over that could continue later without overshadowing the visit.

But surprisingly, the two sides announced that six separate trade disputes at the World Trade Organization were resolved, including one that involved tariffs.

The US is now India’s top trading partner at $130bn in goods and Delhi’s is Washington’s eighth largest partner.

While these numbers are impressive, analysts and policymakers feel there is a huge untapped potential. India is also a burgeoning market with the expanding middle class and it’s been positioning itself as an alternative to China to become a manufacturing hub for the world.

Many global firms and nations are interested in the proposal as they look to free the global supply chain from China’s dominance. In that context, the resolution of trade disputes will give further impetus to unlocking the full potential of India-US trade ties.

Mr Modi has said that “even sky is not the limit (for India-US) ties”.

Critics in Washington have questioned India’s perceived “democratic backsliding” under Mr Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Mr Obama, in a television interview this week, emphasised the significance of addressing the “protection of the Muslim minority in a predominantly Hindu India” during discussions between Mr Biden and Mr Modi.

“The progressives in the Democratic Party are disturbed by what is happening in India. The realists and centrists are all for strengthening the relationship because of the China factor,” says Ms Sirohi.

But on the whole, there is a bipartisan agreement to make the relationship deeper and broader. “India is now a strategic partner and friend,” says Ms Sirohi.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related Topics

-

-

25 March 2022

-

-

-

3 March 2022

-