Who does a textbook really belong to?

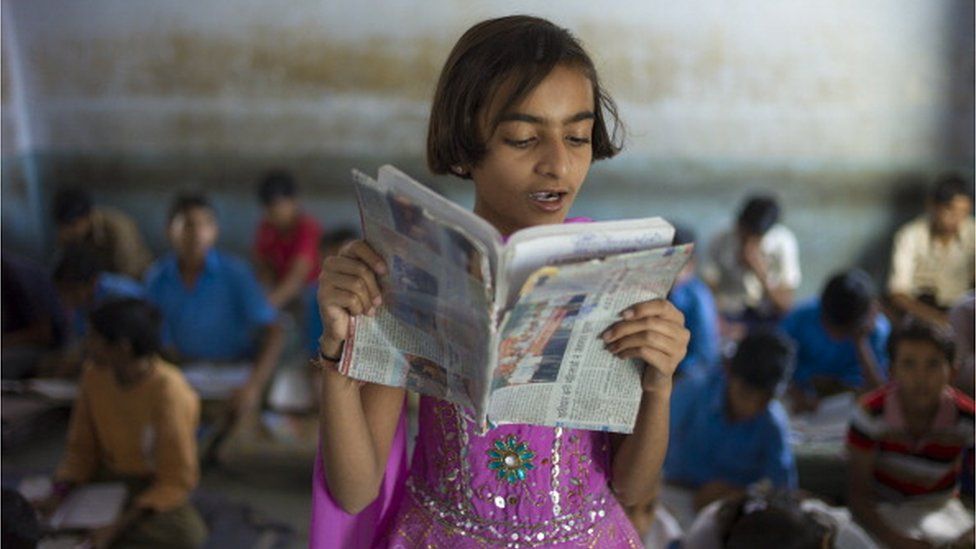

That’s the question being asked in India, where a controversy has been raging for weeks over what children are taught in school after reports about the deletion of some topics in their textbooks.

The textbooks are not new – they were published earlier this year by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) and are already being used in more than 20,000 schools. The NCERT, an autonomous organisation under the federal education ministry, oversees syllabus changes and textbook content for children taking exams under the government-run Central Board of Secondary Education.

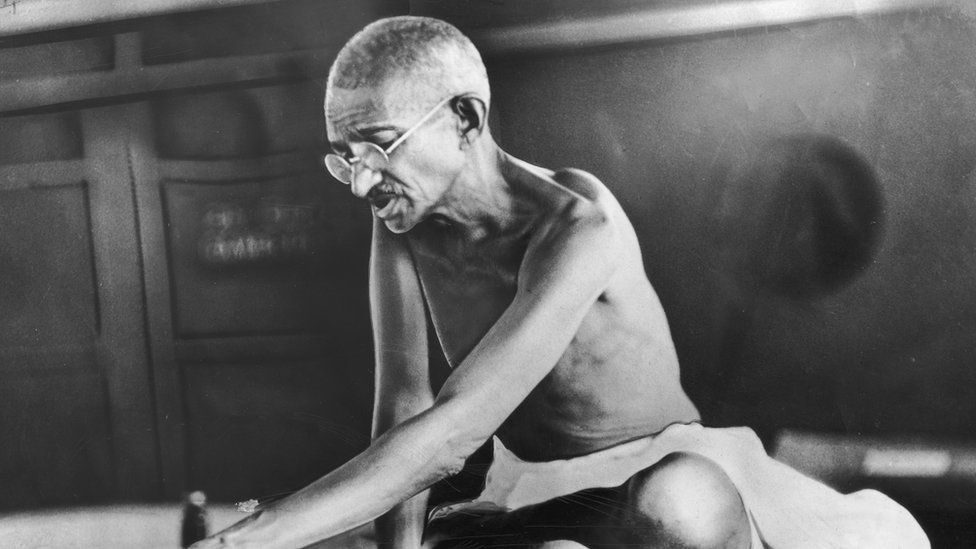

Among dropped topics are paragraphs on attempts by extreme Hindu nationalists to assassinate Mahatma Gandhi and chapters on federalism and diversity.

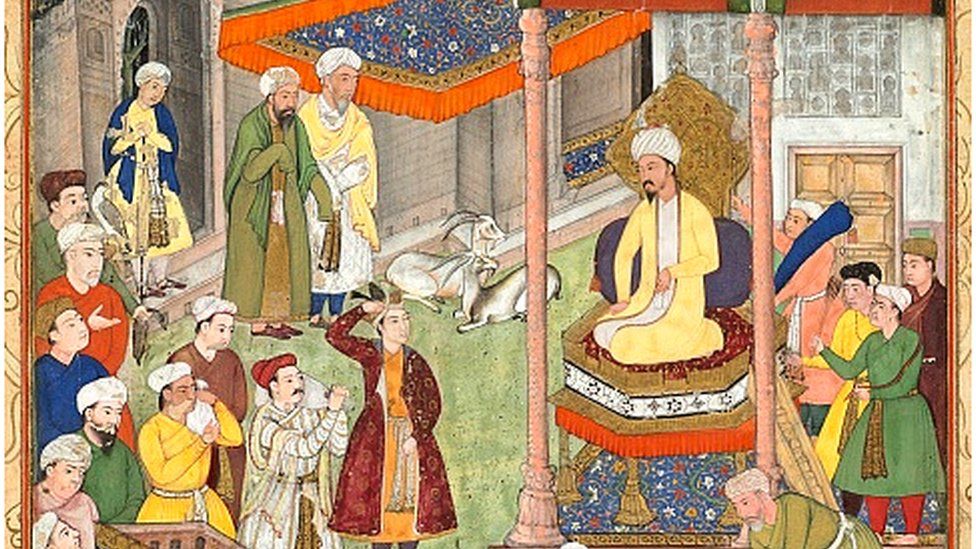

The NCERT has also dropped content related to the 2002 Gujarat riots; removed a chapter on Mughal rulers in India; and moved portions on the periodic table and theory of evolution in science books to higher grades, sparking criticism.

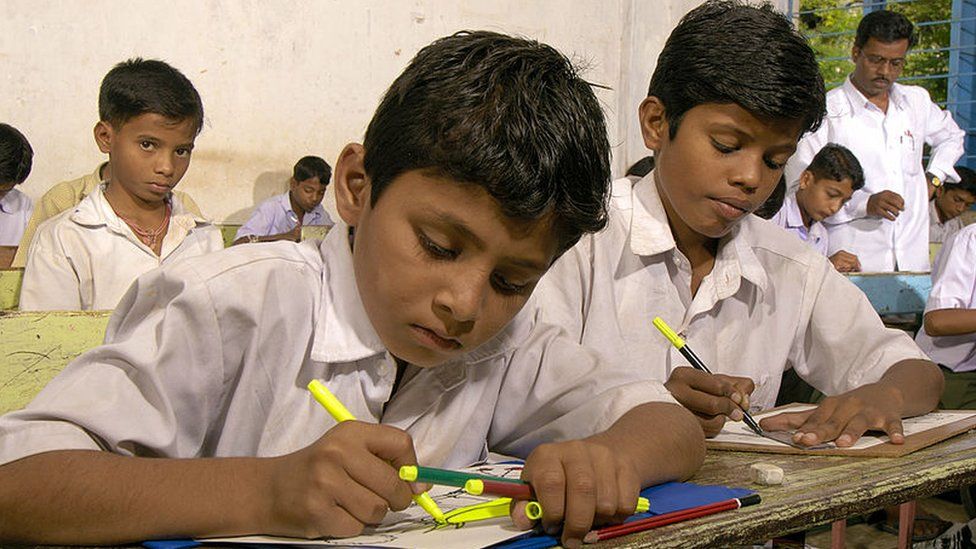

The council had said earlier that the changes, which were first announced last year as part of a syllabus “rationalisation” exercise, wouldn’t affect knowledge but instead reduce the load on children after the Covid-19 pandemic.

But now some academics who were part of committees that helped design and develop the older textbooks say they don’t want to be associated with the new curriculum.

On 8 June, political scientists Suhas Palshikar and Yogendra Yadav – who were advisers for political science books originally published in 2006 for classes 9 to 12 – wrote to NCERT, asking it to remove their names from the print and digital editions of the books.

The academics said they objected to the “innumerable and irrational cuts and large deletions” as they failed to see “any pedagogic rationale” behind the changes.

The NCERT issued a statement saying such a request “was out of question” because it holds the copyright of all the material it publishes. When contacted, NCERT director DS Saklani referred the BBC to the statement on its website.

The deadlock intensified last week when more than 30 academics also wrote to NCERT asking for their names to be withdrawn from the Textbook Development Committees (TDC) listed in the books. The scholars argued that possessing copyright did not entitle the NCERT to make changes to texts they wrote.

But NCERT said that the TDC’s role was “limited to advising how to design and develop the textbooks or contributing to the development of their contents and not beyond this”.

It also clarified that the rationalised content is applicable only for the current academic year and that a new set of textbooks will soon be developed based on fresh guidelines that adhere to the new National Education Policy.

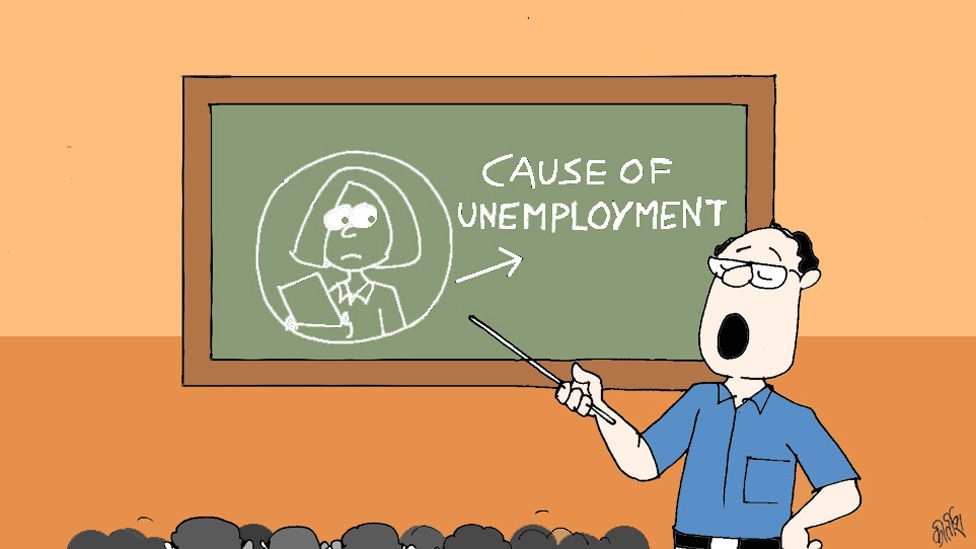

The argument has pitted academics against each other. Critics argue that textbooks should serve as source of introspection and accuse NCERT of erasing portions that are not palatable to the governing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. “The decision of “rationalisation” shows either that the NCERT does not value its autonomy or its leadership does not understand its place in a democracy,” Peter Ronald DeSouza, who asked for his name to be withdrawn, wrote last week.

But the NCERT has also received support. Last week, 73 academics issued a statement arguing that school textbooks were in sore need of an update.

“[The critics’] demand is that students continue to study from 17-year-old textbooks rather than updated textbooks. In their quest to further their political agenda, they are ready to endanger the future of crores of children across the country,” they said.

Supporters include the head of India’s prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and the chief of the country’s university watchdog, the University Grants Commission (UGC).

“Scrutiny should be lauded as long it is rooted in hard facts and evidence. Selective reading and mischaracterisation do not breed transparency or accountability but undermine them,” JNU’s vice chancellor Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit wrote, arguing that the media amplified a lot of “unverified information” on the issue.

Controversies over textbook revision are not new in India – both nationally and at the state level, different governments have often sought to introduce or withdraw changes in line with their ideological beliefs. Most scholars also advocate routinely reviewing the books to update information and strike a balance between content and learning outcomes.

But the critics say this review should be done in a transparent and holistic way.

“Textbooks, as the title the term describes it, hold a sacred place in the education system. Both the teacher and the student rely on them as their first authentic source of how to approach a subject,” Mr Palshikar says.

The NCERT’s textbooks receive a lot of scrutiny as thousands of schools across the country use them. The books are also used for reference by candidates appearing for competitive exams. “So, then the catchment area of these books is huge,” Mr Palshikar says.

Experts say that the role of any thoughtfully designed curriculum is to immerse students in topics that spark discussion, allowing them to encounter questions that are relevant not just to their other coursework but also their lives.

But when there is an “an indiscriminate deletion of some paragraphs and sentences”, the continuity of the argument in the textbook is destroyed, seriously hampering the learning process, Mr Palshikar says.

He adds that they are also objecting to the current deletions because it is not clear what the NCERT’s consultation process was like. “Our only complaint is that if you have consulted anyone else, then put their names rather than our names on the book.”

To evaluate the books in question, the NCERT says it tasked in-house faculty members and external experts, who eventually recommended the changes.

The process accounted for five broad criteria: the overlapping of content among different subjects in the same class; similar content in the lower or higher class in the same subject; difficulty levels; content that is easily accessible to children and “does not require much intervention from the teachers”. And lastly, content “that is not relevant in the present context”.

Relevant information that was removed or rationalised has been included – “either in the same subject in different classes or in a different subject in the same class”, four members of the Council’s textbook team wrote in an article in the Indian Express.

So the periodic table has not been removed entirely from Class 9 and 10 textbooks but instead reassigned to the Class 11 textbook. Mughal history has not been entirely omitted from the curriculum. And Darwin’s theory of evolution is covered in chapter six of the Class 12 textbook.

“No scientific theory is absolute – it can be contested. The latest debates that have questioned Darwin’s theory of evolution need to also be a part of the curriculum”, Ms Pandit from JNU wrote.

However, some experts feel such “arbitrary” changes do more damage than good.

Even UGC chief Mamidala Jagadesh Kumar, who is largely in favour of the rationalisation exercise, agrees with some of the criticism, especially about teaching science.

“The global practice is that topics such as evolution, the periodic table and sources of energy are taught to students before they complete 10th standard,” he wrote this week, adding, however, that the NCERT’s intentions shouldn’t be doubted.

Mr Palshikar points out that the argument comes amid a larger churn in state-funded education in India.

“I think higher education in India has been losing its soul for a long time, particularly in humanities and social sciences because of the pressure to get jobs. The basic purpose of higher education – of questioning and exploring – has been lost,” he says.

“We are currently in the midst of a very small debate compared to that.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

23 September 2015

-

-

-

14 April 2017

-