In just over a month, a wild elephant in India has been captured twice, tranquilised multiple times and relocated over 280km (173 miles) away from its native forest in a bid to keep it away from human settlements in search of food.

Arikomban (“rice tusker” in the Malayalam language) – named for his raids on local shops for rice – has been relocated in the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu even as authorities grapple to secure a permanent habitat. The elephant has also been at the centre of legal battles and a debate on animal rights.

In Kerala, Arikomban has become a “symbol of resilience in the face of injustice,” says activist Sreedevi S Kartha.

“Events have shown how brutal the process of translocation can be for an elephant,” she told the BBC. “It has sparked the conscience of people in the state.”

Earlier this year, a group of locals near Arikomban’s original habitat, Chinnakanal in Kerala’s Idukki district, demanded his relocation after frequent run-ins with humans led to protests.

Officials say the elephant has killed several people over the years – a claim refuted by local tribal communities.

Kerala’s forest department announced that it planned to capture Arikomban and make him a trained captive elephant. Rights activists filed a petition with the high court, urging intervention to ensure the safety of the animal.

Ms Kartha, a member of People for Animals, one of the groups that filed the plea in court, says the government provided no evidence of the elephant killing humans.

In April, a court-appointed committee of experts decided it would be better to translocate the tusker.

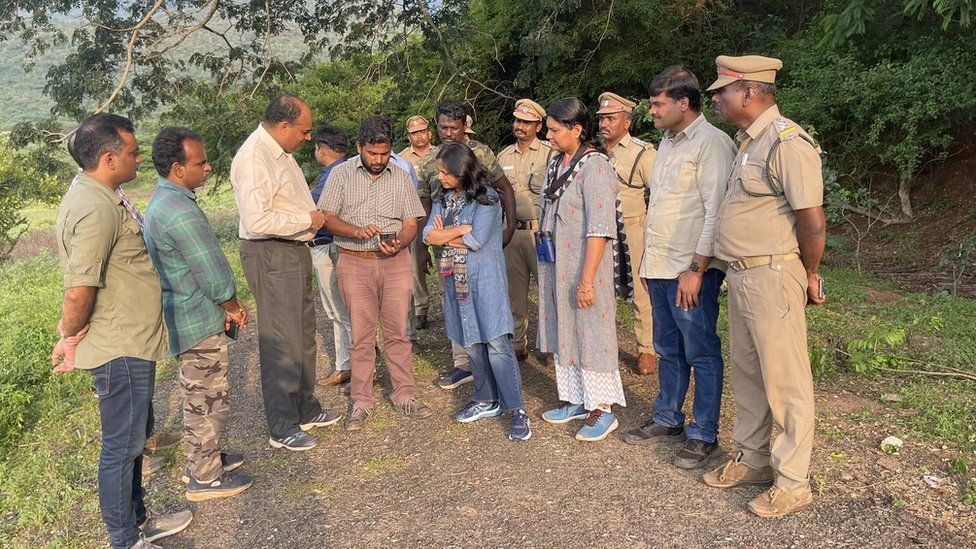

Over two days, 150 officials carried out a massive operation in Chinnakanal to capture Arikomban. On 29 April, the elephant was moved to the Periyar Tiger Reserve about 80km (50 miles) away.

Barely a month later, forest officials in Tamil Nadu, the neighbouring state, found themselves undertaking a similar operation to relocate the animal once more.

The tusker had been spotted in the state’s Cumbum town on 27 May. Videos on social media showed the animal running through the densely populated town, damaging buildings and vehicles. Three people were injured – one of them, a 65-year-old man, succumbed to wounds two days later. Curfew was imposed as authorities tried to capture the elephant.

Arikomban now found himself at the centre of court battles. A politician filed a petition in the Kerala High Court asking for the elephant to be brought back to the state. A petition in the Madras High Court sought compensation for the damages he had caused in Tamil Nadu.

Kerala’s forest minister, AK Saseendran, said the crisis vindicated his government’s plan to make Arikomban a captive elephant and blamed activists for the elephant’s translocation.

But the Cumbum incident showed that Arikomban was not a threat to human life, Ms Kartha says. “He was traumatised and chased but did not attack human beings there.”

On 5 June Tamil Nadu’s forest officials tranquilised and captured the tusker. Visuals of Arikoban’s latest capture raised concerns about the number of times the tusker had been tranquilised and the injuries the animal had suffered as he was transported by officials in an open truck.

Stephen Daniel, a wildlife activist, said that the animal was paying the price for policy decisions by government that led to human settlements on the path of elephant routes.

“The mental and physical agony the animal was undergoing is unfathomable and the forest departments of the two states have a lot to answer for,” he said.

Back in Kerala, tribal groups in Chinnakanal have demand that the elephant should be returned to its original habitat. They plan to approach the courts to bring the tusker back.

“What is the need to capture and shift the elephant to the tiger reserve if it is made to suffer in such a manner?” one protester told the news channel Malayala Manorama.

Tamil Nadu’s forest department said Arikomban had been relocated deep inside Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, over 200km (124 miles) away from Cumbum.

Reports said locals living nearby protested its relocation, worried that the tusker could wreak havoc in their settlements.

Supriya Sahu, a Tamil Nadu forest official, said the translocation had been “successful”. His new habitat had “dense forest and plenty of water” and the elephant was eating well, she said in an update on Twitter.

The state’s forest personnel were also camping in the reserve, monitoring Arikomban’s health and tracking his movements.

“He’s in good health and his wounds have healed,” forest official Srinivas Reddy told BBC Tamil last week.

But recent events prove the elephant will return to residential areas even after it is moved deep into the forest, Mr Saseendran told reporters.

“Translocation is only a temporary solution,” he said. “We can’t say the tusker won’t return to Kerala.”

Forest officials in Kerala remain on alert in case Arikomban ventured close to the state’s borders.

“Elephants have strong homing instincts,” Ms Kartha says. “Arikomban has been trying to come back home ever since he was first translocated [in April].”

“If he ventures back to human settlements, bring him back to Kerala – that’s the only permanent solution,” she says.

With additional reporting by Meenu Mathew.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

- The divisive debate over California’s anti-caste bill

- Delhi: The city where it is dangerous to breathe

- Why it took 42 years to convict a 90-year-old in India

- Haunting images of deadly India train crash in 2002

- How did three trains collide in India?

- ‘My mother was missing, I got a picture of the body’