Kathleen Folbigg has been called many names. A “baby killer”, “Australia’s worst mother”, a “monster”.

But on Monday, Ms Folbigg said she was “extremely grateful” as she walked free for the first time in 20 years, after being pardoned of killing her four children.

The historic decision follows one of the worst miscarriages of justice in Australian history, her lawyers say, and it has held up a microscope to what experts call “demonstrably unreliable and misogynistic” evidence that helped convict her in 2003.

It was a case mired in suffering that created a media frenzy and saw Ms Folbigg’s husband testify against her at trial.

Ultimately it would be the advocacy of friends and new findings from scientists around the world – including Nobel laureates – that saw her freed.

Re-examining the original conviction

Ms Folbigg, who has always maintained her innocence, has lived a life haunted by trauma.

Before her second birthday, her father – who had a history of domestic abuse – stabbed her mother to death. In the year that followed, she shuffled between the homes of relatives before finally being fostered to a couple in Newcastle, New South Wales (NSW).

It’s an incident that prosecutors would later use against Ms Folbigg at trial, to argue she was predisposed to violence.

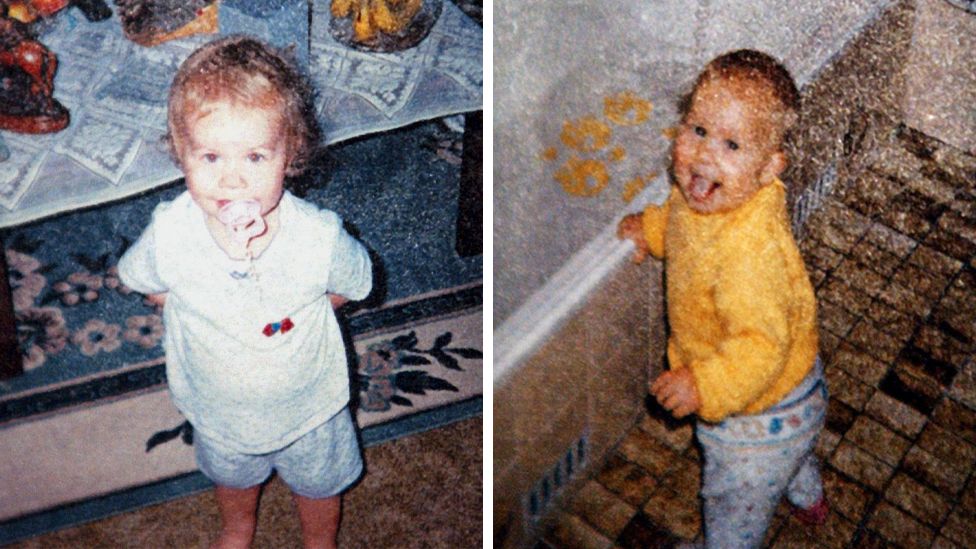

In 2003, she was sentenced to 40 years in prison for the murders of her children Sarah, Patrick and Laura, as well as the manslaughter of her first son Caleb.

All four children had died suddenly between 1989 and 1999, aged between 19 days and 18 months. Prosecutors alleged Ms Folbigg had smothered them.

Caleb, who had been suffering from mild laryngomalacia – a condition that impacts breathing – died in his sleep in 1989.

Patrick, who was diagnosed with cortical blindness and epilepsy, died soon after as the result of a seizure. Sarah and Laura – who had both suffered from respiratory infections – also died in their cots.

Ms Folbigg’s sentence was later reduced on appeal to 30 years, but she lost a string of challenges against her convictions. A 2019 inquiry into the case only gave greater weight to the original circumstantial evidence used to jail her.

But this week a fresh inquiry, headed by retired judge Tom Bathurst, concluded there was reasonable doubt over Ms Folbigg’s guilt, due to new scientific evidence that her children could have died of natural causes because of incredibly rare gene mutations.

The research was spearheaded by Carola Vinuesa, a professor of immunology and genomic medicine at Australian National University. She first began looking into the case in 2018 amid growing concerns from medical experts.

After sequencing Ms Folbigg’s DNA, Prof Vinuesa and her team created a genetic map, which they then used to identify mutated genes.

One of the most significant, known as CALM2 G114R, was present in Ms Folbigg and her two daughters. Stunningly, research has linked it to a rare condition that occurs in one in every 35 million people, and can cause serious cardiac abnormalities.

That’s because the CALM G1142R genetic variant can interfere with the passage of calcium ions into cells – that ultimately can stop the heart from beating.

The research from Prof Vinuesa’s team also uncovered that Caleb and Patrick possessed a different genetic mutation, linked to sudden-onset epilepsy in mice.

The findings tipped the scales in Ms Folbigg’s case, proving that the chances of her children dying from cardiac abnormalities in infancy were disturbingly high.

A debunked theory and other flaws

It was her daughter Laura’s death in February 1999 that sparked the initial police investigation into Ms Folbigg.

“My baby’s not breathing,” she told an ambulance operator at the time, speaking from her home in the rural town of Singleton.

“I’ve had three Sids [sudden infant death syndrome] deaths already,” she continued in a recording, which was later played at her trial.

Laura’s death meant Ms Folbigg and her husband Craig Folbigg had lost all of their children.

But while Mr Folbigg was initially interviewed and arrested as part of the investigation, he soon began helping the police build their case against his wife, handing over her personal diaries and testifying against her.

During the 2019 inquiry into the case, he refused to provide a DNA sample requested by her lawyers. Mr Folbigg’s lawyers say he remains convinced of his ex-wife’s guilt to this day.

The prosecution’s main argument in the 2003 trial was that it was a statistical improbability that so many of Ms Folbigg’s children could have died accidentally.

In their reasoning, they cited a now widely discredited legal concept known as “Meadow’s Law”, which contends that “one sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious and three is murder until proved otherwise”.

The principle is named after Roy Meadow, who was once described as Britain’s most eminent paediatrician. But his reputation declined rapidly after a string of wrongful convictions in cases that relied on his theory.

In 2005 he was struck off the UK’s medical register for giving misleading evidence in the trial of Sally Clark – a solicitor who was found guilty and jailed for the murders of her two infant sons in 1999.

Ms Clark’s conviction was quashed in 2003, but relatives said she never recovered from the trauma of her ordeal, and she died from acute alcohol poisoning in 2007.

Emma Cunliffe, a law professor at the University of British Columbia who wrote a book examining Ms Folbigg’s case, says Meadow’s Law was “heavily challenged by medical research” from its inception, and “always at odds with the principle that the state bears the burden of proving crime beyond a reasonable doubt”.

“In Commonwealth countries, the practice of charging mothers based on a suspicion about a pattern of infant death in a family, more or less ceased entirely after 2004,” Prof Cunliffe explains.

“Ms Clark’s wrongful conviction was the first salvo against Meadow’s Law. But it was the case of Angela Cannings in 2004 in which the English Court of Appeal said “this reasoning has no place in our courts”.

“It should have then been excluded from legal reasoning entirely, but it took longer in Australia.”

It wasn’t the only flaw in Ms Folbigg’s case. The evidence used by the prosecution was entirely circumstantial, relying on Ms Folbigg’s diaries – which were never examined by psychologists or psychiatrists at trial – to paint her as an unstable mother, prone to rage.

In one entry, penned in 1997 shortly after her daughter Laura’s birth, Ms Folbigg wrote: “One day [she] will leave. The others did, but this one’s not going in the same fashion. This time I’m prepared and know what signals to watch out for in myself.”

This and similar comments were argued to be an admission of guilt. But in a 2022 inquiry into the case, psychological and psychiatric experts rejected this portrayal.

“In relation to the diary entries, evidence suggests they were the writings of a… depressed mother, blaming herself for the death of each child, as distinct from admissions that she murdered or otherwise harmed them,” NSW Attorney General Michael Daley said when announcing Ms Folbigg’s pardon this week.

Prof Cunliffe argues that at its core Ms Folbigg’s conviction in 2003 relied on “casual misogyny” and “thinly veiled stereotypes about women”.

“Within a criminal case when a mother is suspected of harming children, the notion of what constitutes good mothering becomes a lot narrower, so behaviours that are seen as mundane are cast as suspicious,” she says.

Prof Cunliffe adds the prosecution used “discriminatory reasoning” to depict Ms Folbigg as a supposedly unfit mother, in order to cast her as a killer.

“They pointed to the fact that she was leaving Sarah on Saturday mornings with family members to work at a part-time job to earn more money for the household as evidence that she didn’t love Sarah, didn’t want to care for her, and therefore was capable of murdering Sarah,” she says.

‘First time sleeping properly in 20 years’

In a video statement after her release, Ms Folbigg said she felt “humbled” by her pardon, but that she would “always grieve for… and miss” her four children.

Her first night out of prison was spent eating pizza with her oldest friend Tracy Chapman – who had led the campaign to see Ms Folbigg freed.

“She slept in a real bed. She’s actually said it was the first time she’s been able to sleep properly in 20 years,” Ms Chapman later told reporters.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Though Ms Folbigg was given a pardon, her convictions remain – meaning she still faces a long road ahead if she wishes to have them quashed and seek compensation.

The first step will be for retired judge Tom Bathurst to file a full report on the case, before referring it to the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal which will have the final say.

“There’s no good automatic process in Australia for evaluating questions of compensation in circumstances where wrongful convictions arise,” Prof Cunliffe says.

“Yet again, Kathleen will find herself potentially having to engage in an adversarial process in order to prove her entitlement to compensation.”

As for the ripple effects of the case – experts argue Ms Folbigg’s pardon has shed light on how slow Australia’s legal system was to respond to new scientific findings.

“The question must now be asked: how do we create a system where complex and emerging science can inform the justice system more readily?” the Australian Academy of Sciences said in a statement this week.

-

-

16 March 2007

-