On Thursday, a judge calmly delivered an extraordinary ruling that will go down in Australian history.

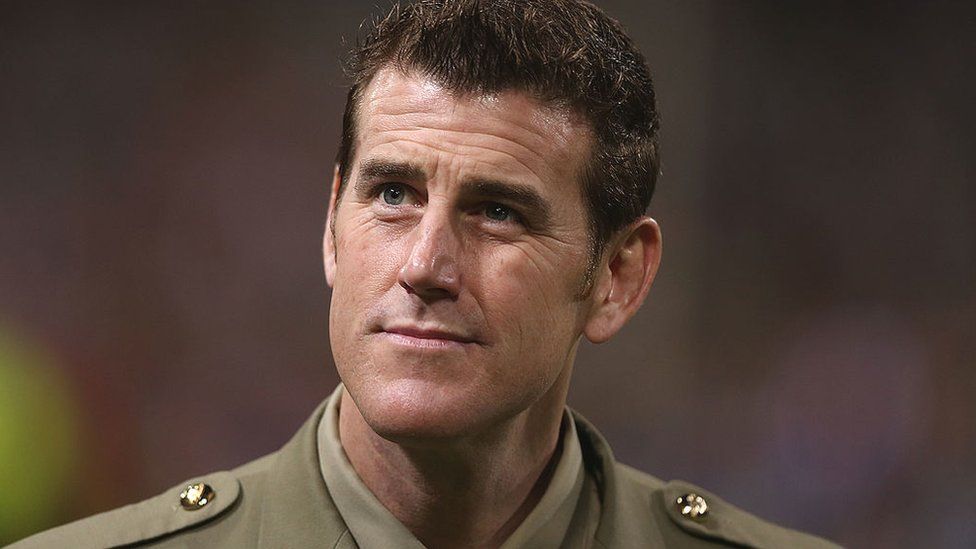

The country’s most-decorated living soldier, Ben Roberts-Smith, had lost a defamation case against three newspapers who reported he had murdered unarmed prisoners and civilians while serving in Afghanistan.

The newspapers’ allegations that Mr Roberts-Smith was actually a war criminal, a liar and a bully were “substantially true”, the judge said in his civil case ruling.

The case is the first time an Australian court has assessed accusations of war crimes by Australian forces – ahead of what many predict will be a wider reckoning in the years to come.

‘Disastrous miscalculation’

Justice Anthony Besanko’s finding that four of six murder allegations – all denied by Mr Roberts-Smith – were in fact true shredded what was left of the Victoria Cross recipient’s reputation.

The former soldier’s decision to launch the defamation case has been called a “disastrous miscalculation” and an “expensive own goal”, and it could have far-reaching consequences for him.

With the civil case dismissed, attention has turned to whether Mr Roberts-Smith will now face criminal charges.

That’s unclear, legal experts say, because civil trials require a far lower burden of proof – the newspapers only had to show the allegations were more likely to be true than not.

Dr Jelena Gligorijevic, a senior lecturer in law at the Australian National University (ANU), says prosecutors will now have to decide whether there is sufficient evidence to prove the murders “beyond reasonable doubt”.

“That’s very, very different from proving on a balance of probabilities,” she tells the BBC.

“This defamation judgement is not at all conclusive on whether they will prosecute, and then whether they will be successful.”

There are already calls for Mr Roberts-Smith to be stripped of his military honours, and for glowing tributes dedicated to him in the Australian War Memorial (AWM) – which include portraits and his uniform and medals – to be removed.

On Friday, the AWM said it was now “considering carefully the additional content and context to be included” in displays which reference the former Special Air Service (SAS) corporal.

Others however have said that Mr Roberts-Smith is innocent until proven guilty in a criminal court, arguing no action should be taken until that point.

Mr Roberts-Smith’s lawyer has said they will comb the full defamation case judgement, leaving the door open for an appeal.

But the civil trial is already rumoured to have cost around A$25m (£13.2m; $16.3m). Traditionally, the losing party of any civil suit pays the legal costs of each side.

And Mr Roberts-Smith is newly unemployed. On Friday, his employer – Seven West Media – said it had accepted his offer to resign from a high-ranking role.

Dozens of investigations under way

The trial has also unearthed more tough questions for Australia’s army, which has long been considered by the public to have a distinguished legacy.

“People express great pride in the way in which Australia has fought – this is what’s known as the Anzac legend,” says Peter Stanley, the former principal historian at the AWM.

That legend is famously traced to a doomed offensive carried out by Australian troops at Gallipoli, Turkey, in World War One. It embodies a spirit of “egalitarianism and mutual support” that Australians still turn to in times of hardship and conflict, according to the AWM.

Each year, Anzac Day brings millions of Australians together at dawn ceremonies to remember those who served, and in particular, those who did not make it home.

Once feted as a paragon of the Anzac legend, Ben Roberts-Smith has now become the face of accusations Australian soldiers committed war crimes.

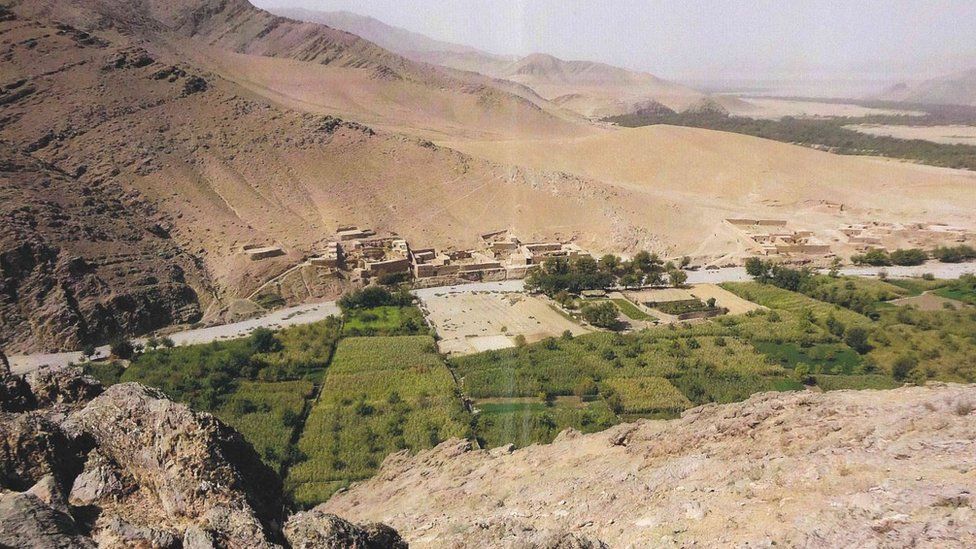

In 2020, a landmark investigation known as the Brereton Report found “credible evidence” that elite soldiers unlawfully killed 39 people in Afghanistan.

It kept most details a secret but said the allegations included what was “possibly the most disgraceful episode in Australia’s military history” – a redacted event which occurred in 2012.

The four-year-long inquiry found a “warrior culture” within Australia’s special forces, and recommended that 19 current or former soldiers should be investigated over alleged killings of prisoners and civilians from 2009-13.

Earlier this year former SAS soldier Oliver Schulz became the first person to be charged with the war crime of murder.

In the wake of the report, Australia’s government set up an Office of the Special Investigator (OSI), which confirmed last week that “40 matters” are currently under joint investigation with the police.

Mr Roberts-Smith’s actions “certainly fall within the scope” of the OSI’s work, says international law Prof Donald Campbell from the Australian National University.

But none of the evidence presented in the defamation case can be used in any criminal trial, and investigations would have to start afresh, he says.

“The government has supported the special investigator because they know that if they are going to bring any successful criminal prosecutions, they need to go out and collect evidence in Afghanistan,” he tells the BBC.

Regardless of whatever further evidence is gathered, many experts say the Brereton Report and testimonies from Mr Roberts-Smith’s case warrant a deeper reckoning.

“We have to not forget that Ben Roberts-Smith and others accused of war crimes were not operating alone,” says James Connor, a military sociologist at the University of New South Wales.

“They were always under the command of others. They were always part of a group, and responsibility for what went wrong has to be shared widely.”

“That’s not to diminish their actions… but the culture is rotten and the cover-up which has flowed from that is also rotten.”

Australia’s reliance on “tiny” numbers of professional soldiers carrying out multiple tours of duty in conflict zones is another thing “that we ought to reflect on”, Prof Stanley says.

Last year, a secret report obtained by the Guardian Australia under freedom of information laws warned of morale issues and a “high demand” for mental health services among Australia’s elite forces.

“We cannot put people into harm’s way repeatedly without appropriate support and oversight of what they’re doing and how,” says Mr Connor.

He argues the Australian Defence Force has had a “cultural problem” for “decades”, and that secrecy, tribalism and “misguided loyalty” have been allowed to flourish.

“Defence has tried to argue that it’s a few bad apples, or perhaps even a bad barrel here and there… but overall, the culture needs to change and change rapidly,” he adds.

But Prof Stanley believes the painful examination of the darker chapters of Australia’s war record could eventually provide a redemptive moment.

“Characteristically Australians believe in a fair go, [which] involves things like admitting that things go wrong, and investigating them if need be,” he says.

“Australians might be embarrassed or even ashamed that these allegations have been made, but the fact that Australia is openly and properly investigating them is, I think, a source of pride.”