The Myanmar military is suffering defections from its forces and is finding it hard to recruit. In exclusive interviews, newly-defected soldiers tell the BBC that the junta, who seized power in a coup two years ago, is struggling to suppress the armed pro-democracy uprising.

“No-one wants to join the military. People hate their cruelty and unjust practices,” says Nay Aung. The first time he tried to leave his base he was badly beaten with a rifle butt and called a “traitor”.

He managed to escape the second time and flee across the border to Thailand with the support of opposition groups.

“One of my friends is in the resistance,” he says. “I called him and he told people here in Thailand about me. I arrived here with their help.”

He’s now living in a safehouse along with 100 other newly-defected soldiers and their families. These men, who refused to fight their own people, are now in hiding so we are not using their real names. They’re being housed and protected by the very resistance movement they were ordered to fight.

Since the military seized power in a coup in February 2021, more than 13,000 soldiers and policemen have defected, according to the exiled National Unity Government of Myanmar (NUG). They are offering cash incentives and support to try and get more soldiers and police officers to switch sides.

At 19, Maung Sein is the youngest in the safehouse. He joined the military when he was just 15 years old.

“I admired the military,” Maung Sein says, and he wanted to make his family proud. But the military’s violent crackdown on the nationwide uprising demanding democracy has dramatically changed people’s view of men in uniform.

“We saw online people calling us ‘military dogs’,” he says – the animal term is one of the biggest insults in Myanmar. “That made me sorry and sad.”

Maung Sein says foot soldiers like him couldn’t disobey “orders from above” to “kill civilians and burn villages”.

But he also left because he thinks the military is in a weak position.

Ethnic armed organisations in the border regions alongside a network of civilian militia groups, called the People’s Defence Forces (PDF), are proving to be a much stronger force than many expected and the Myanmar military has lost control of large parts of the country.

In Magway Division and Sagaing Division, places that previously provided the military with many recruits, young people are instead joining the civilian militia.

Before managing to defect, Maung Sein’s unit was ordered to “attack and destroy” a PDF training camp.

The operation didn’t go well. Seven of his fellow soldiers were killed before they were ordered to retreat. “They [the PDF] have a better strategy,” he says, “which makes them stronger.”

The PDF enjoys widespread public support and villagers provide intelligence about the military’s movements and shelter the young militia fighters.

Capt Zay Thu Aung spent 18 years in the air force. He defected a year after the coup in February 2022.

“They are under attack across the country,” he says, reflecting on the state of Myanmar’s army, “and they don’t have enough men to fight back.”

This is why, he says, the military is increasingly using the air force.

In recent months the military has carried out devastating air strikes across the country. Since January there have been more than 200 reports of air attacks. The deadliest airstrike hit the Pa Zi Gyi village in Sagaing region in April, killing more than 170 people, including many women and children.

“Without the air force, it’s very likely that the military will fall,” Capt Aung predicts.

Like the other defectors, everyone in his family was proud of him when he was chosen as an air force cadet. In those times, he says, it was an honour to be part of Myanmar’s military. The coup, he says, “pulled us down the abyss”.

“Most of the people I lived with in the air force were not bad people. But since the coup, they’ve been acting like monsters.”

He’s the only one in his unit who has defected, though. Most of his friends have “kept fighting against my people”, he says.

Despite the Myanmar military’s critical role in the country’s affairs, its exact size is unknown. Most observers estimate at the time of the coup it was around 300,000 but now is much lower.

The resistance has used new technologies like video games alongside traditional crowdfunding mechanisms to raise money, much of it individual donations from the diaspora.

They have managed to raise significant sums this way but they lack access to military grade weapons or fighter jets.

The National Unity Government has offered to pay $500,000 (£405,000) to regime pilots or sailors who defect with a military aeroplane or navy vessel, but so far no-one has done this.

With the Myanmar military strategy turning increasingly to the air, with devastating consequences, the BBC follows those fighting back.

And on BBC News on Sat 3 Jun at 04:30, 23:30 and Sunday 4 Jun 02:30 BST

Or listen to Assignment on BBC World Service

Capt Aung says it’s not easy to leave after being “indoctrinated for years” and that he, too, feared being seen as a traitor.

“There is a saying in the Myanmar military that you leave when you’re dead.”

Russia’s role

Before defecting, Capt Aung worked on a major upgrade of the capital Naypyidaw’s airport to prepare for the arrival of advanced fighter jets from Russia, the Sukhoi Su-30M.

Capt Aung takes us through the satellite imagery of the airport. He shows us where he used to live and where he helped build three open sheds to house the six Sukhoi Su-30M’s ordered.

These fighter jets represent “the most advanced aircraft in the arsenal of the Myanmar military,” says Leone Hadavi from Myanmar Witness, who has been monitoring the aircrafts the military is using.

He says the Sukhoi Su-30M is an advanced multi-role fighter jet that has both air-to-air and air-to-ground capabilities in the version that was exported to Myanmar.

It has a greater capacity to carry weapons than the Russian-made Yak-130s that have been regularly sighted in recent airstrikes.

Capt Aung says as part of the agreement two test pilots from Russia and a repair crew of 10 people would stay for “one year during the entire warranty period”. He was involved in building their accommodation.

Others from the Myanmar air force were sent to Russia. “Altogether more than 50 people were sent to be trained to operate these planes,” he tells us.

Two of the six fighter jets have arrived in Myanmar and been put on display at military parades. They have not yet been sighted in the conflict.

In the face of international sanctions and condemnation from its neighbours, the Myanmar military has become increasingly isolated. The latest round of UK sanctions in March attempted to target the military’s access to fuel.

But Russia – who has long-running ties with the Myanmar military – has stepped up to become their strongest foreign backer.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur for Myanmar, Tom Andrews, says Moscow is by far Myanmar’s largest arms dealer. According to his report released in May, Russia has shipped over 400 million dollars’ worth of arms to Myanmar since the coup.

These come from 28 Russian entities, including state-owned ones. The report says 16 of those suppliers have been sanctioned by some countries for their role in Russia’s war in Ukraine. And that these weapons have been used to “commit probable war crimes and crimes against humanity” in Myanmar.

In the air, the people’s resistance is trying to fight back with drones.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Khin Sein, 25, leads a team of female drone pilots who adapt civilian drones to drop home-made bombs on military targets.

She was a university student and took part in the mass protests sparked by the coup before taking up arms.

“We don’t have the resources like the military but we don’t dwell on this,” she says from her jungle camp.

“Compared with a plane, our drone is like a sesame seed. It can go far when you have many sesame seeds,” she says.

“If we fly high, like 300 metres above, they don’t even know that we are coming. So we can attack them effectively and they are scared of drones.”

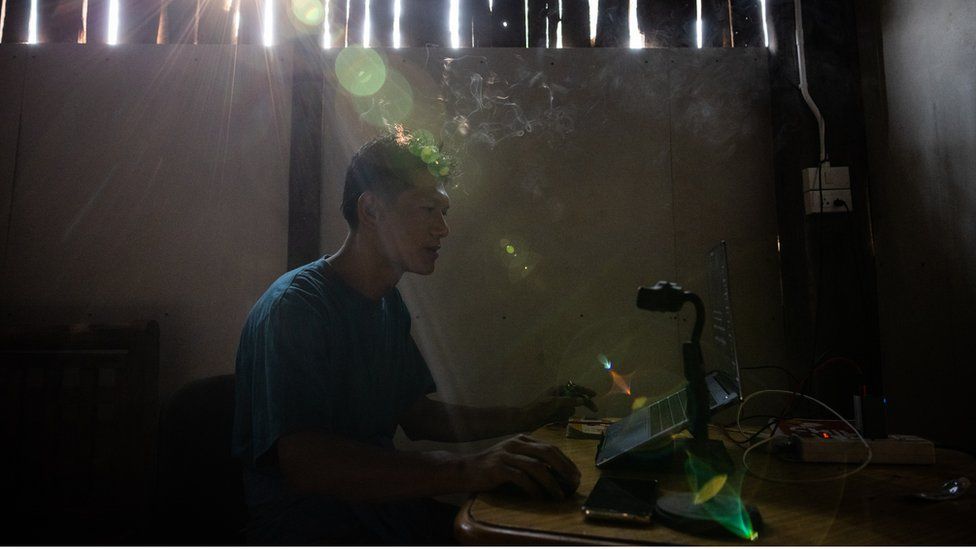

From his hideout across the border in Thailand, Capt Aung now shares his air force intelligence with those like her, fighting for democracy.

“By listening to the sound at night, can we distinguish between a fighter jet and a civilian plane?” comes the crackled voice over Zoom in the back room of his house.

“We share our knowledge in the best way we can”, Capt Aung says after the meeting.

It is complex for him, “on a personal level, my brothers, friends and teachers whom I lived with, I have no hatred for them,” he tells us.

But this cause is bigger. “It’s not about individuals, we are fighting an institution.”

And he’s happy, he says because “I’m working for my country. I’ll support the revolution in whatever way I can until it’s over.”

Related Topics

-

-

1 February 2022

-