When Miguel Pantaleon was ordained into the Catholic church last month, it was the biggest day of his young life.

The 28-year-old trainee priest had spent almost a decade working towards joining the clergy. At a packed mass in his dusty village of Rincon del Carmen in western Mexico, he was officially brought into the priesthood by the diocese bishop.

Watching in the front pew, his mother, Petra Florencio, beamed with pride. Miguel is the 11th of 13 children, and his vocation is a source of great prestige for his family.

However, Petra would also be forgiven for harbouring a few doubts: Miguel has joined the riskiest priesthood in the world.

More than 50 priests have been killed in Mexico since 2006, nine of them under the current administration alone. Some were killed for speaking out against cartel violence, others caught up in the crossfire of an unending conflict between rival criminal organisations.

Almost always, the murders go unpunished and unsolved – the authorities often carrying out only the most cursory of investigations.

Many of the killings took place in the western region of Mexico called Tierra Caliente, where in recent years the Jalisco New Generation Cartel and the Familia Michoacana gangs have battled for territorial control.

“To me, becoming a priest here in Tierra Caliente signifies love,” Miguel told me after the service. “These are people who live with a lot of pain, hurt and suffering. So, when we respond to God’s call, it’s a sign of His love.”

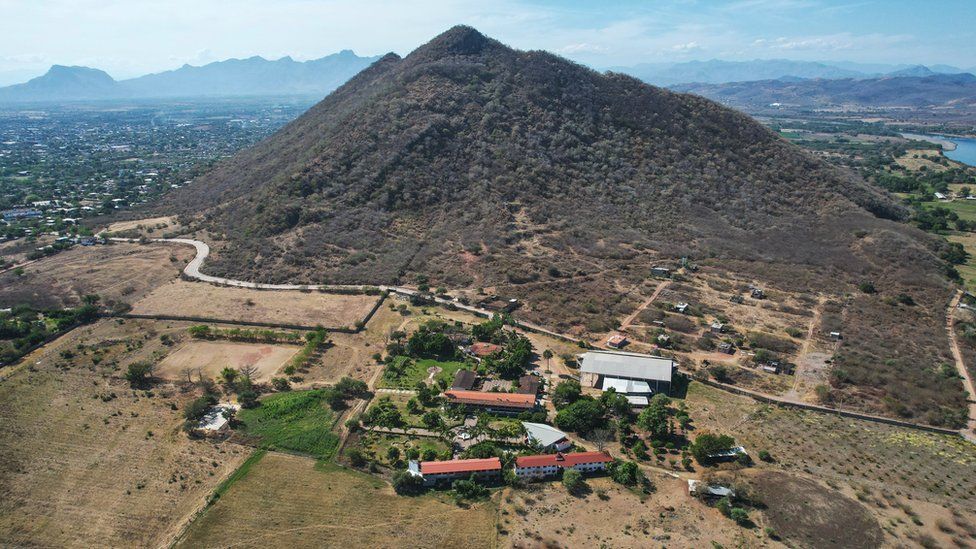

Miguel studied at a seminary several hours drive into the heart of Tierra Caliente, outside the city of Ciudad Altamirano.

Every morning, as the 18 trainee priests at the seminary gather in the chapel for morning mass, they walk past a stark reminder of the dangers they’ll face as clergy: the grave of a murdered priest who taught at the seminary.

On a simple granite tombstone, a wrought-iron name plate reads: “Father Habacuc Hernández Benitez, 16 January 1970 – 13 June 2009.”

Father Habacuc – better known as Padre Cuco – is something of a local martyr, a symbol of the many murdered clergymen and seminarians in Mexico.

“The year Padre Cuco was killed marked a parting of the waves in the violence in this region,” recalls his friend, Father Marcelino Trujillo. “Before then, the drug cartels were more discrete, there was still a degree of governability.”

The story of Padre Cuco’s murder is still shocking, more than a decade on.

The 39-year-old priest was on his way to a youth event with two seminarians. Gunmen surrounded their car and forced the men out of their vehicle. Without a word, they were executed at the side of the road, shot multiple times in the backs.

No clear motive was ever established.

Marcelino was supposed to be with his fellow instructor that day, but a last-minute change of plans meant he didn’t leave the seminary. A twist of fate which surely saved his life.

It wasn’t the only time the tight-knit seminary has been thrust into mourning by drug cartel violence.

On Christmas Day 2014, Father Gregorio, a cousin of Cuco’s, met a similar fate. In an astonishingly brazen attack, he was taken from one of the rooms in the seminary, gang members tied him up and gagged him with gaffer tape.

“He asphyxiated,” explains Marcelino. “As far as we understand, they planned to demand a ransom for him but on finding they’d killed him, they just abandoned him in nearby scrubland.”

Such stories might deter any local young men, no matter how devout, from joining the clergy in Ciudad Altamirano. But between classes, some of the seminarians told me the opposite is true, that the murdered priests are an inspiration, not a warning.

“They’ve been clear examples to us,” says 19-year-old Antonio Abelez. “Such unfair deaths, they serve us as examples of their bravery.”

The seminary rector, Antonio Reinoso, says they teach the young men to exhibit “prudence” as priests – to restrict themselves to preaching the gospel and to think carefully before denouncing criminal gangs or cartel leaders at the pulpit.

“Organised crime is a beast with a thousand heads,” he tells me. “They are not going to be able to solve the violence themselves. But, with faith, they can meet it head on.”

Still, the seminarians acknowledged they’ve sometimes questioned the wisdom of their decisions to join the church.

“We live surrounded by violence and death,” says Guillermo Cano, a student in his early 20s. “Given what people have been through, it intimidates us to think we could meet the same fate.”

Back in Rincon del Carmen, most of the village has turned out to celebrate their newly ordained priest, Father Miguel Pantaleon. In a procession from the church, they follow him through the streets with song, fireworks and fiesta.

As Miguel celebrates with his family and friends, he insists he’s ready for whatever lies ahead.

“I know that one day I’ll have to come into contact with the cartels,” he says, “but not to confront them – rather, to show them the face of God’s mercy, because God is for them, too.”

Related Topics

-

-

5 February 2022

-