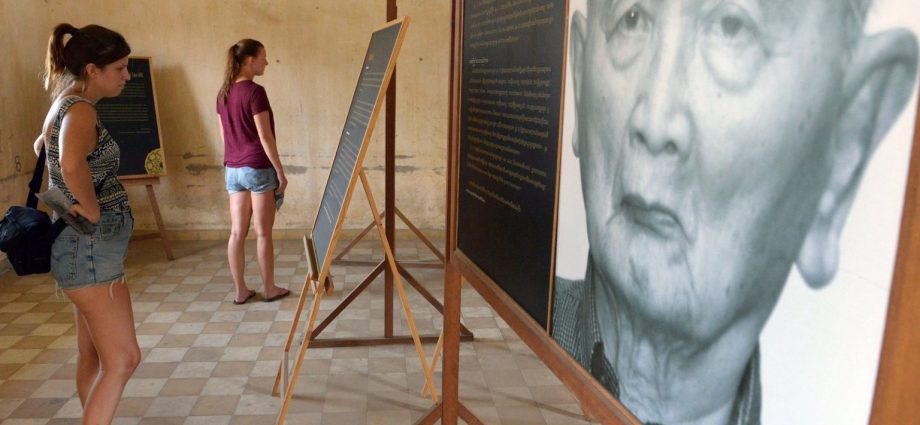

A United Nations-backed tribunal in Cambodia has just concluded its largest trial, concerning crimes committed during the Khmer Rouge regime. The tribunal’s appeal judges yesterday confirmed the conviction against 91-year-old Khieu Samphan, the former head of state, for his role in these crimes.

Yesterday’s decision was a turning point. After this, there will be no further trials in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. But what will the lasting impacts of these trials be?

The Khmer Rouge, otherwise known as Communist Party of Kampuchea, held power in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979. Their assent to power followed a period of violent authoritarianism, conflict and the loss of half a million lives during US bombing in the Vietnam war.

While many Cambodians initially welcomed the Khmer Rouge’s victory, this popular support was short-lived. Life under Khmer Rouge rule meant forced labor, starvation, and the constant threat of torture, imprisonment and death.

Prosecuting the crimes of the Khmer Rouge

In 1979, the Vietnamese defeated the Khmer Rouge and installed a tribunal to prosecute Communist Party of Kampuchea Prime Minister Pol Pot and Deputy Prime Minister Ieng Sary in absentia.

After that largely symbolic effort, there was no accountability for the crimes of the Khmer Rouge for several decades.

However, following negotiations between the Cambodian People’s Party (still in power) and the UN, in 2003 a tribunal was established to prosecute senior Khmer Rouge leaders and “those most responsible” for the crimes.

Known officially as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, this UN-backed tribunal started work in 2006. Its jurisdiction covers crimes defined in Cambodian law and international law, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

There is now a permanent court to prosecute these kinds of crimes: the International Criminal Court in The Hague. But it can only address crimes committed after 2002, whereas the UN-backed tribunal in Cambodia’s mandate reaches back to the 1970s.

The trials

In its 16 years of operation, the UN-backed tribunal in Cambodia has completed just three trials.

In the first trial, it found Kaing Guek Eav (alias “Duch”), former head of the S-21 prison, guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes.

S-21 was used to torture suspected enemies of the regime. An estimated 12,000 men, women and children were detained there; only 12 are known to have survived. Duch’s conviction was upheld on appeal, and he died in prison in 2020.

The next case concerned four Communist Party of Kampuchea senior leaders: Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith.

But Ieng Thirith was found unfit to stand trial in 2012 and Ieng Sary died in 2013, leaving only two defendants in the case.

Due to the complexity of the case, the tribunal split it into two phases.

In 2014, the tribunal convicted Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan of crimes connected to the expulsion of Cambodia’s urban population into rural worksites. This conviction was mostly upheld in 2016, with both defendants receiving a life sentence.

In 2018, it convicted both men of further crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide.

This conviction covered forced labor, the torture and execution of suspected dissidents, crimes targeting ethnic, political and religious groups, and orchestrating forced marriages with a view to incentivizing population growth.

The judgment also recognized many rapes by Khmer Rouge cadre in worksites and prison sites, although these crimes were not formally charged.

Both men appealed the 2018 judgment, but Nuon Chea died shortly after at age 93, leaving Khieu Samphan as the sole appellant.

Genocide

The case that ended yesterday was the Cambodia tribunal’s only case to include charges of genocide.

Nuon Chea was convicted of genocide against the ethnic Vietnamese and Cham groups; Khieu Samphan was convicted of genocide against the ethnic Vietnamese only.

These legal findings do not necessarily square with popular conceptions of genocide in Cambodia, where “genocide” has come to mean the atrocity crimes against the entire population.

But in international law, “genocide” is defined more narrowly – it only captures crimes committed with an intent to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.

Nor do the tribunal’s genocide findings necessarily accord with the perspectives of the targeted groups.

Our research suggests the Cham and ethnic Vietnamese communities do not always draw clear distinctions between their experience, and that of the broader Cambodian population. While they wanted the tribunal to recognize their suffering, this did not have to include a conviction of genocide targeting them exclusively.

But ultimately, these legal details may not matter. It seems the 2018 genocide conviction was meaningful for many Cambodians, who viewed it as affirming their experience of “genocide.”

What next?

Many Khmer Rouge leaders died before they could be indicted, and attempts to prosecute other suspects were blocked by the Cambodian government.

Now, attention is turning to the tribunal’s legacy.

Already, there are signs it affected the historical record. For example, the pattern of forced marriage and sexual violence recorded in its judgments was not widely acknowledged by Cambodian or Western historians prior to these trials.

But the full extent of the tribunal’s impact will take decades to assess.

It is yet to be seen whether it affected the rule of law in Cambodia, whether its judgments and reparations brought a meaningful sense of justice to survivors, and how the judgments will influence understanding of the regime and its crimes.

Rosemary Grey, Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney and Rachel Killean, Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.