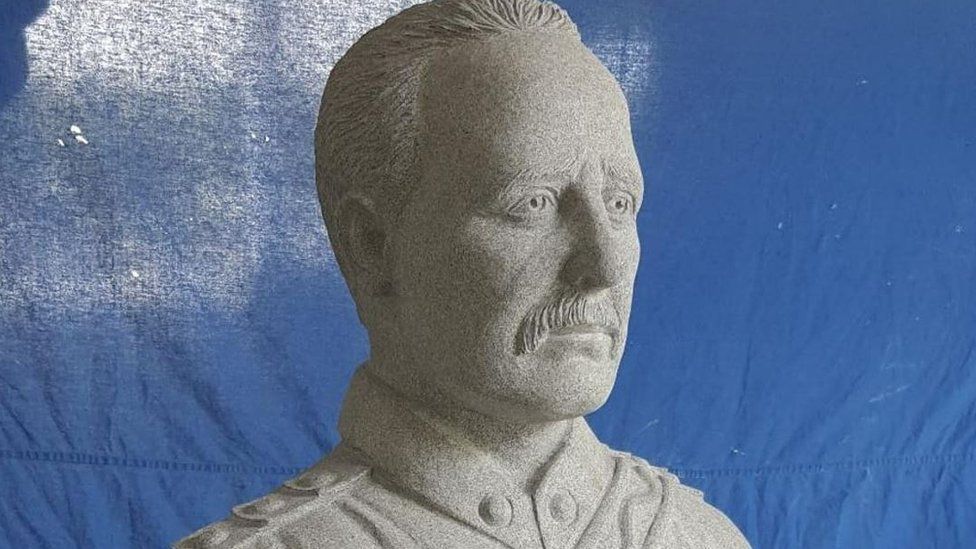

An Indian state provides gifted the breast of a colonial-era Uk engineer to his hometown of Camberley in England.

The particular statue of Colonel John Pennycuick — donated by the southern part of Tamil Nadu state – will be revealed on 10 September at a public park in Camberley, 50km (31 miles) from London.

Pennycuick is really a revered figure within Tamil Nadu to get designing and constructing the Mullaperiyar dam, which provides water meant for drinking and irrigation to five zones in the state.

The particular 127-year-old dam has long been a source of tension between Tamil Nadu and neighbouring Kerala state, that has often called for its demolition.

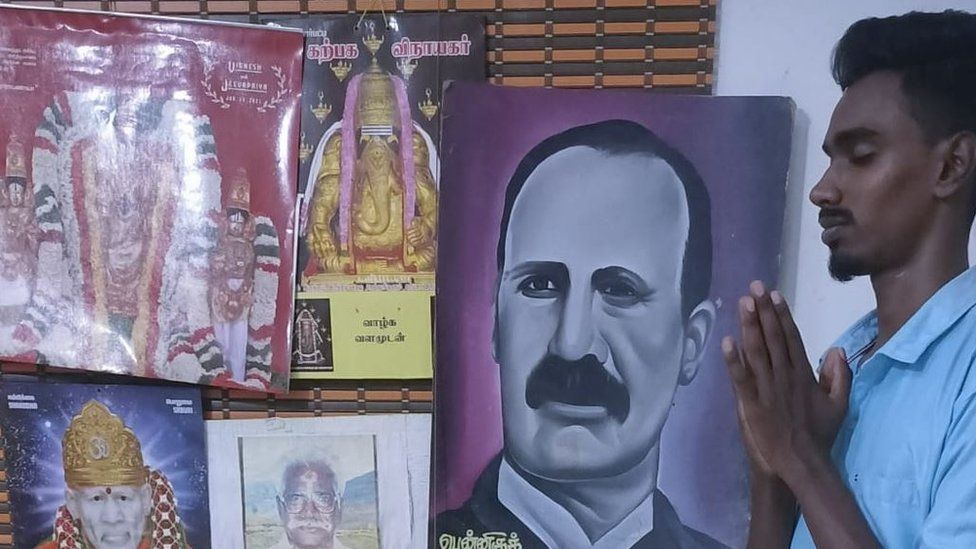

But Pennycuick’s legacy remains strong in Tamil Nadu, especially in the five districts which get drinking water from Mullaperiyar. In one of them, Theni, photos of Pennycuick suspend in shops, homes and government offices. Many baby kids are named Pennycuick while some have called their daughters Sarah after the engineer’s mother.

“His work has not yet been fully recognised. Only people in our condition [Tamil Nadu] knew about him, ” says Santhana Ibrahim, a London-based documentary maker who is the driving pressure behind the task to install the statue.

The making of Mullaperiyar

Pennycuick was created in the western Indian native city of Pune within 1841. After receiving military training in London, he returned in order to India to join the particular British Indian military as an engineer.

Later, he joined the general public works department from the erstwhile Madras Obama administration, an administrative neighborhood in the south from the country.

Murugesh

Generally there, he worked on developing the Mullaperiyar dam, which would transfer water from the west-flowing Periyar river to the Vaigai river, which ran in the other path.

In a paper entitled The Diversion from the Periyar, written around 1897, Pennycuick says that the idea of creating a dam had been mooted much earlier.

“The first recorded expression of it dates from the beginning of the present century, when surveys were made for the purpose of determining how far the proposal was a practical one particular, ” he produces.

But the surveys, which were made “in a somewhat half-hearted manner”, found the idea “impracticable”, according to the paper.

That will didn’t dissuade Pennycuick, who set about getting his design approved. Construction began on the end of 1888.

The chosen web site “was in an desolate, unoccupied jungle, seven kilometers from the nearest stage of a cart-road, twenty miles from the closest cultivated land”, he or she writes.

Building materials were carried on boats plus carts. Work needed to be stopped for months in between because of jungle temperature, and later, heavy rains and water damage.

Records show between 4, 500 and 6, 500 labourers worked on the project, which was designed in 1895.

Getty Images

“At the conclusion of the 19th Millennium we had very few dams in south Indian, ” says K Sivasubramaniyan, a retired professor who has examined water management within Tamil Nadu for many years.

The Mullaperiyar dam, he says, was obviously a “great engineering accomplishment which helped finish the water scarcity for people living in five areas in present-day Tamil Nadu”.

‘Like the god’

Desika Thiruvalan, 32, quit her job in a tech company a few years back to oversee her family’s farms. They will own around 20 hectares of property in Theni area.

She states she is able to harvest two crops of rice every year, while her ancestors needed to rely on unpredictable rains to irrigate their crops.

“Pennycuick is much like a god to us. We are blessed to have plenty of water, ” she states, adding that prior to the dam, there were periodic famines and droughts in the region.

Desika Thiruvalan

Ms Thiruvalan’s ancestor Peya Thevar had been one of the locals who have supplied food to the workers who constructed Mullaperiyar.

“When my husband went to the Hindu temple to execute a memorial support, he mentioned Pennycuick’s name along with the ones from our ancestors, ” she says.

Through the years, many myths are suffering from around the engineer’s heritage. In 2016, Pennycuick’s great-grandson told Indian newspaper Mint that he had “no evidence” of a popular declare that the engineer utilized his own resources to create the dam.

As the engineer was a household name in parts of Tamil Nadu irrigated by the dam, somewhere else in the state not everyone had heard about him.

One namesake, now 20 years previous, says as a child he was bullied at school due to his name.

“I experienced very awkward and was even upset with my dad for choosing it, ” recalls Pennycuick, a student who else uses only one title.

Gubendran

Pennycuick’s dad Gubendran had relocated jobs from Madurai district, where the engineer is celebrated, to central Tamil Nadu where he was less well known. To help his son understand the significance of the name, Gubendran took him whenever he was 12 to see the dam, as well as a memorial to the engineer who had built it.

It was the life-changing moment for the young boy.

“There, I saw a sculpture of John Pennycuick and immediately noticed how big his accomplishments were, ” this individual recalls. “Tears folded down my cheeks. ”

Reviving a legacy

While the dam is in Kerala, Tamil Nadu operates it under a 999-year lease agreement to irrigate farmland on its side of the state border.

The dam has seen the share of controversies. In the late 1990s, Kerala expressed worries over its problem, triggering years of political and legal wrangling.

In 2014, India’s Supreme Court ruled that the dam was safe, based on the findings of an specialist panel, but its drinking water storage level has been reduced – plus Kerala is still seeking legal options.

“The dam helped irrigate about 340, 1000 acres [134,000 hectares] of property, but that has at this point halved, ” says Prof Sivasubramaniyan.

The controversy over the dam has only burnished Pennycuick’s legacy in Tamil Nadu.

“It was only about 15 years ago that people started partying his birthday in public places, ” Ms Thiruvalan says.

Santhana Ibrahim

His followers, however , add that celebrating Pennycuick does not mean endorsing British colonialism.

“Pennycuick, due to his sheer determination, could build a dam which is still standing and providing water to all of us. We are just stating thanks to him, inch Ms Thiruvalan states.

After retirement, Pennycuick returned to Britain. He died within 1911 at Camberley, where he was hidden. In 2019, the senior Tamil Nadu police official given a bust of Pennycuick which was set up in the garden in which the engineer was smothered.

Mr Ibrahim, the film maker, hopes the new statue he is helped to set up will interest nearby residents in Tamil Nadu and its lifestyle.

As for Pennycuick the student, he is at ease with his name and now includes a dream.

“One day I will go and find out the statue associated with Pennycuick in England. inch

Read more India stories from the BBC:

- India’s Gandhi begins 3, 500km walk to revive party

- India insists on seat belts after tycoon’s death

- Motorboats replace cars within ‘India’s Silicon Valley’

- India mother injured fighting to save baby from tiger

- Inside India’s ‘factories of death’

- Why are Native indian men screaming along with period pain?

More on this particular story

-

-

24 December 2021

-