The late American social commentator Will Rogers has been quoted as saying, “Buy land. They ain’t making any more of the stuff.”

The global population is about to surpass the 8 billion mark. Meanwhile climate change, soaring costs of living, and sharp increases in the price of fertilizer mean the global food system could face its most difficult period in decades. Unless we find a cure to droughts, egocentric politicians, and the energy bonanza, things could get out of hand soon.

From another point of view, though, every crisis is an opportunity. This time, for example, the main beneficiaries could be farmland owners.

Data suggest that 73% of farms marketed in the UK in the past year sold at, or for more than, their guide, the highest level since 2014. Demand continues to outweigh supply.

Knight Frank’s Farmland Index shows the average value of farmland in England and Wales is rising at the fastest rate since 2014. Thus we could say that it is a good alternative for long-term investors – though only, of course, for those who can afford it.

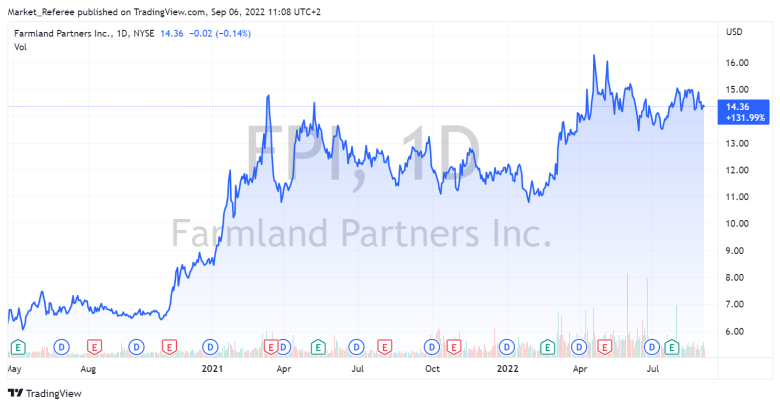

As for the US, for the past 30 years, the average return on farmland in the country, adjusted for inflation, has been around 5%.

No wonder Bill and Melinda French Gates have acquired more than 108,800 hectares of farmland in the United States over the past decade. The Land Report suggests that the land is used to cultivate vegetables such as carrots, soybeans and potatoes.

Meanwhile another billionaire, Warren Buffett, owns a 600-hectare family farm in Pana, Illinois, and three foundation-operated research farms, including more than 600 hectares in Arizona and 3,700 hectares in South Africa.

Other large financial firms have sought to purchase agricultural land, too. The US Department of Agriculture estimates that about 30% of US farmland is rented out by owners who serve as landlords and aren’t involved in farming.

According to some reports, investors from China are also acquiring prime US farmland to gain control over agribusiness ventures.

Risk of a bubble about to burst?

After the 1980s farm crisis, fueled by tight money policies, legal changes to agricultural tenancies, and record production, the US government has taken as much of the risk away from agriculture as possible with its crop insurance program. Yearly government subsidies also protect farmers from price declines and poor yields. Such subsidies cost taxpayers more than $5 billion annually.

Thus it is doubtful that history will repeat itself. The US Department of Agriculture forecasts net farm income to increase by $7.3 billion (5.2%) from 2021 to $147.7 billion in the calendar year 2022. Farm-sector equity is expected to increase by 10.4% in 2022 to $3.34 trillion in nominal terms. Farm-sector assets are forecast to increase 9.7% (nominal) in 2022 to $3.84 trillion after expected increases in the value of farm real estate assets.

Overall, the limited and shrinking availability of agricultural land could continue to push farmland prices up. Some even suggest that despite short-term profitability concerns, perspectives for land values are positive because of the growing demand from alternative investors and new income-stream opportunities.

But there is a serious caveat. The world is going through historic climate changes that cause droughts and floods. Lack of water, brutal heat and other climate issues are plaguing an industry wholly dependent on weather. According to recent US government figures, for example, more than 32% of land in western states is experiencing extreme or exceptional drought conditions.

Thus drastic climate conditions could affect the quality of some farmland; as a result, its value might actually decrease.