Reuters

ReutersA skull rolled towards my feet.

It would have hit my trainers if it hadn’t been blocked by the zipline of a body bag it had just been thrown inside.

Next to me, Gemma Baran, 44, watched in horror as more of her husband’s bones were loaded into the bag.

Gemma had buried Patricio Baran here five years ago but she could no longer afford to lease the cemetery plot – in crowded Manila, the poor often lie in rented graves, nearly $200 (£164) a piece.

But she was recently offered a different grave for Patricio – this one for free – by a local church programme, “paghilom” or “healing”.

It supports families of those who have been killed in the vicious war on drugs that has catapulted the Philippines into global headlines in recent years.

Patricio, a 47-year-old security guard, was shot dead on 9 July 2017.

He had disappeared the day before. A neighbour heard three shots but didn’t see the assailants. The police say Patricio’s body was found next to a gun and a sign that read: “pusher and rapist”.

But Patricio’s family rejects this, saying he had never sold or used drugs. Gemma says he had become embroiled in a land dispute in the weeks before his death.

She even suspects that he was killed in connection with it, but she is fearful of publicly contradicting the police.

Gemma says that since Patricio was killed, she’s been struggling to pay rent and provide for her three children. She cleans homes for a living and also relies on food handouts from her church: “I’m really suffering. I don’t know what to do for my children.”

She says her children are also the reason she hasn’t pushed for an investigation into her husband’s death: “I’m really scared. I’m staying silent.”

On that sunny June morning, Father Flavie Villanueva prayed over Patricio’s remains as the body bag was zipped up and he was carried away to another resting place.

“We decided to start this programme to help the victims’ grieving families rebuild and empower their lives anew,” said Father Villanueva, a Catholic priest who has long campaigned against outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte’s government.

“Duterte’s order of ‘kill, kill, kill’ is a deliberate state-sponsored command that has produced thousands of widows and orphans. This is the president’s most tragic legacy.”

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Duterte’s war on drugs

Mr Duterte’s brutal crackdown on drugs has its supporters.

It has lessened the number of “evil elements”, says Ofelia, a mother of four who lives in Pinyahan, northern Manila, a community that once experienced high drug-related crime.

In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, two masked gunmen crossed through police quarantine checkpoints to kill an alleged drug user, locally known as Bulldog, just 30 metres from Ofelia’s house.

Ofelia, who had voted for Mr Duterte, was sad about Bulldog’s death because she knew and liked him.

“It’s painful. A second chance should have been given to him to change, not something so sudden.”

But she also endorses the campaign, adding that drug use is no longer visible in her neighbourhood – although she says that her life was neither better nor worse since Mr Duterte took office.

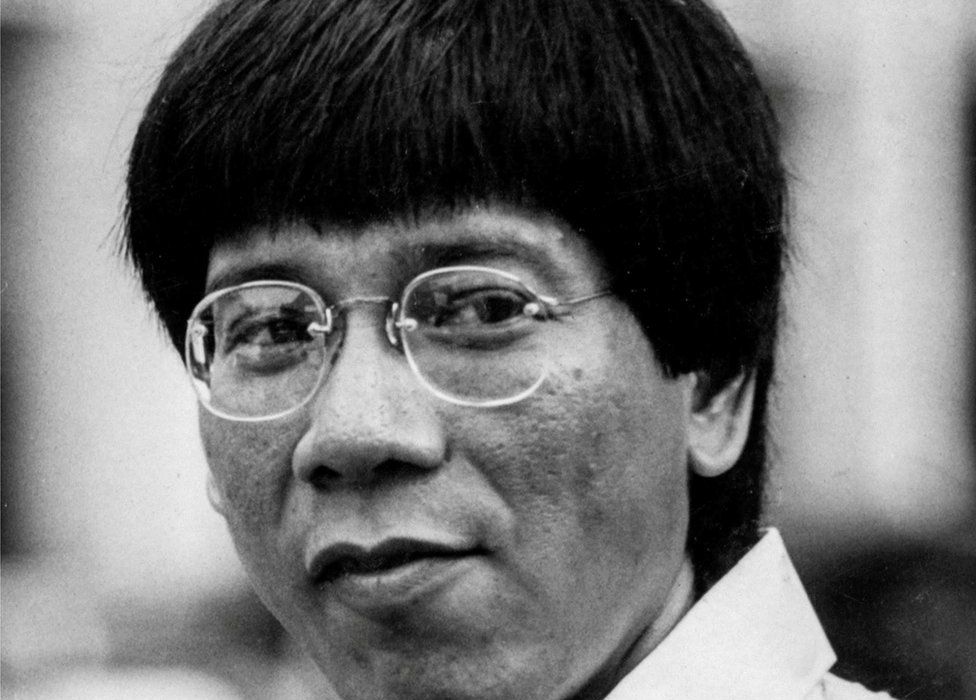

Rodrigo “Digong” Duterte, who is 77, was elected in June 2016 on a hardline ticket to clamp down on drugs and crime.

His signature policy – the so-called “war on drugs” – has seen thousands of suspected drug addicts and dealers killed in controversial police operations. Thousands more have been shot dead by unidentified masked gunmen, often referred to by the Philippines’ media as “vigilantes”.

Many also point to evidence of growing police impunity as a fallout from the drug war – in 2020, an off-duty police officer was caught on camera shooting his neighbour after an argument, sparking huge public anger. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Shortly after I arrived in Manila in 2017, 32 alleged drug dealers were killed in a single evening in a police operation labelled “drug war, double barrel reloaded”.

Many of the victims’ families have insisted their loved ones were innocent – and human rights groups and the international community have decried the violence.

But Mr Duterte has been unfazed. He once boasted he’d be “happy to slaughter” three million drug addicts in the Philippines, falsely comparing his anti-drug campaign to the Holocaust – and bringing swift condemnation from Germany and Jewish groups.

Mr Duterte’s government has consistently dehumanised drug addicts and dealers – and its supporters on social media have often referred to them as “rapists and killers” who deserve to be killed.

His foreign secretary Teodoro Locsin Junior sparked global outrage with a series of tweets invoking the Holocaust, including one that said the Philippines’ “drug menace is so big it needs a final solution like the Nazis adopted”.

I recently asked Mr Locsin if he saw similarities between the Holocaust and the killing of alleged drug addicts and dealers in the Philippines.

“No” was his reply, but he admitted to problems in policing: “We’re trying to fix that. But we will not in the interim allow the drug trade to get such a grip on our political life that we can’t reverse it, so that we end up like Central America.”

The true toll of the war on drugs will never be known. At first, the official count, which combined confirmed deaths during police operations and the killings by masked men (the government called them deaths under investigation, or DUI) ran into tens of thousands. But then the government dropped the DUI metric and the number fell.

The latest official figure – for the number of alleged drug dealers and users killed between July 2016 and April 2022 – is 6,248. But human rights groups believe the number could be as high as 30,000.

The police have always said that they only killed in self-defence. But CCTV footage, photographs of victims suggesting that they were incapacitated, and the accounts of whistle blowers point to something more sinister. A Manila police captain was secretly recorded in a 2019 documentary – On the President’s Orders – saying that it was officers who were carrying out the masked killings.

Mr Duterte had once told law enforcers at an anti-drug event: “You might be shot. Shoot him first, because he will really draw his gun on you, and you will die. For me, I don’t care about human rights… I will assume full legal responsibility. I will face those human rights [lawyers], not you.”

The popular strongman

All of this has done little to dent his popularity – his ratings have stayed high throughout despite international condemnation and an ongoing investigation into alleged crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.

Some have attributed this to his aggressive populism in a poor country where public faith in the judicial system has always been low, while others say Mr Duterte, despite his long political career, projected himself as something of an outsider – as opposed to the Aquino and Marcos families that have governed the Philippines for decades.

Over the years, he modelled himself as a “punisher” who “broke the rules”. His blunt and often crass choice of words resonated with ordinary Filipinos, with some even referring to him as “tatay Digong” or “Father Duterte”. His misogynistic comments about women and sexist remarks over rape have been passed off by his supporters as “just jokes”.

But neither his provocative personality nor his open encouragement of violence is new.

Mr Duterte rose to power in the 1980s when the Philippines was still steeped in Cold War politics.

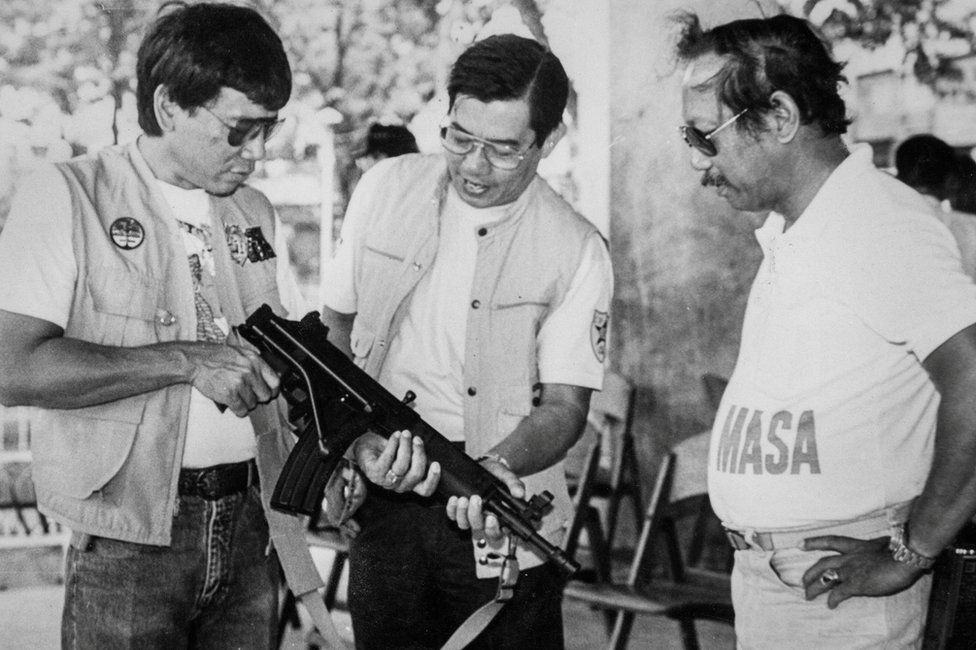

Davao, a key southern city where he became mayor in 1988, was the centre of the resistance that sprang up against armed Communist rebels who were targeting police, officials and others they saw as their enemy.

Much of this resistance – called Alsa Masa (Masses Arise) – was driven by arming civilians, and according to some reports even forcing them, to fight the Communists. Some experts believe the United States, too, had a role to play given that, fresh from a costly defeat in the Vietnam War, it had been helping arm anti-Communist fighter groups across the world.

When asked if the US had ever been involved in supporting Alsa Masa, Mr Locsin said: “If they were, I would basically have to shoot myself if I told you so. It was a tough world. It was a world that got things done. That is unimaginable now. We’re not the same people now.”

Alsa Masa, many believe, is the origin of the vigilante groups and so-called “death squads” that emerged in Davao under Mr Duterte – the victims were often leftists, opponents and alleged criminals, including drug users and dealers.

An investigation into more than 1,000 of these killings and disappearances in Davao by the UN implicated Mr Duterte. At a 2016 senate hearing into the killings, police whistle blowers described how a “Davao death squad” planted guns and drugs on victims to frame them.

Mr Duterte, however, has always insisted he never gave direct orders to kill. But in 2018 he said, “My only sin is the extrajudicial killings.”

Shrinking democratic space

Mr Duterte vowed big ticket infrastructure spending and easing of restrictions on foreign direct investment, but the pandemic and an ensuing recession obscures his economic record.

He did a “good job” of handling the economy, according to April Tan, chief equity strategist of COL Financial in Manila. “He allowed his technocrats to do their work. The tax system was successfully reformed. A lot of measures were passed that improve the incentive to do business here.”

Government ministers also praised his handling of a peace deal that offered improved political autonomy for millions of Muslim Filipinos on the southern island of Mindanao in return for the decommissioning of weapons.

He also banned public smoking and pledged free university education and improved healthcare, but it’s too early to measure the success of these initiatives.

One of his biggest promises – to cut corruption – included launching a helpline where people can report graft. But in 2021, his own government faced corruption allegations over multi-billion dollar contracts awarded to a healthcare supplier. Mr Duterte reacted by barring his cabinet from attending senate hearings investigating the matter, and no legal action followed, leading critics to claim that impunity for the rich and the powerful continues in the Philippines.

Another casualty of Mr Duterte’s presidency has been free speech. Opposition leaders have been jailed and critics have been targeted, including Father Villanueva, the Catholic priest who prayed for Gemma’s husband Patricio. He is charged with sedition.

Media, too, have been stifled – Maria Ressa, Nobel Peace Prize winner and co-founder of the Rappler news website, has been convicted of cyber libel. She has denied the charges and appealed against the verdict. Many believe the allegations against her are politically motivated over Rappler’s hard-hitting coverage of Mr Duterte’s policies. She also faces a daily barrage of online trolling, designed, she says, to “bludgeon you into silence”. On the eve of Mr Duterte leaving office, the Rappler website was ordered to shut down by officials.

Mr Duterte might not belong to a political dynasty but he has certainly started one – he leaves office as his daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio takes over as vice-president. She won on a landslide and could well be preparing for a presidential run in 2028.

Mr Duterte’s supporters insist his record is commendable: “Mr Duterte has left so many legacies, it will take you several days to enumerate them,” his former spokesperson Salvador Panelo said.

He dismissed the investigation by the International Criminal Court into the vigilante killings, saying “it’s the drug syndicates who have been killing each other”.

But Mr Duterte’s critics say his legacy is marred by the violence. “When you’re in government you can do good [as president], just by sitting there, because things happen,” said Karen Gomez-Dumpit, the outgoing head of the country’s commission on human rights.

“You have the whole apparatus of government at your beck and call. He could have done very well, had he not had that kind of policy.

“It’s a legacy of killing,” she said. “Safety at the expense of human rights? Is that real safety?”