TopFoto

TopFoto In 1933, the sari-clad teenager produced international headlines.

Avabai Wadia, 19, became the first woman from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to pass the pub exam in the United Kingdom. Her success encouraged the Ceylonese government to permit women to study law in the country.

This was not really the only time Wadia spurred government guidelines on women’s rights. By the time she passed away in 2005, the girl had become an internationally respected figure within the family planning motion, combining a lawyer’s acumen with a dedication to socially enjoyable women.

Wadia was born in 1913 in a progressive Parsi household in Colombo. Right after qualifying as a lawyer, she worked both in London and Colombo despite omnipresent “masculine prejudice”.

She moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) throughout World War Two and immersed herself in social function, but found the girl true calling in family planning.

“It seems my entire life work presented alone to me rather than the consciously searching for it, ” she published in her autobiography, The Light is Our bait. “I did not feel it a waste not to carry on with a legal career, for law was a fortifying aspect in all that I began. ”

When the girl began working in area in the late 1940s, family planning was obviously a taboo topic across much of the world.

Aside from stoking opposition from religious conservatives, it also had unsightly links with racism and eugenics.

“The first time I heard the words ‘birth control’, I was revolted, ” Wadia noted. But she was profoundly affected by a female doctor in Bombay who said that Native indian women “oscillated between gestation and lactation until death wound up the sorry tale”.

TopFoto

Despite the threat of interpersonal ostracism, Wadia stepped into the cause.

In 1949, the girl helped establish the Family Planning Association associated with India (FPAI), an organisation she would mind for 34 yrs.

FPAI’s work ranged from promoting birth control method methods to providing fertility services – the latter gave Wadia “a real sense of satisfaction” since the lady had suffered miscarriages and had no children. It was in large part because of Wadia’s efforts which the Indian government grew to become the first in the world to officially promote family members planning policies within 1951-52.

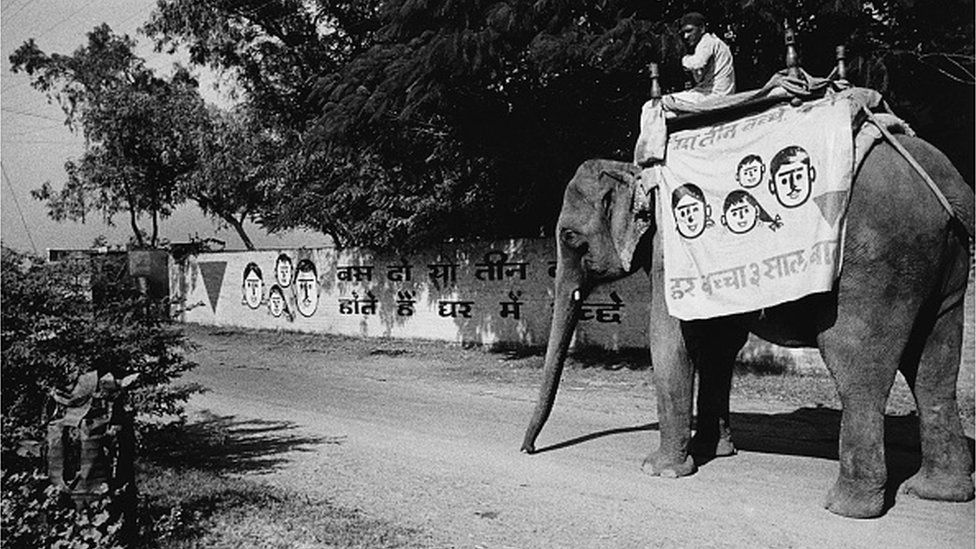

Under Wadia, FPAI adopted the decentralised, community-based approach, working with the urban poor and villagers from some of the most impoverished regions of India.

This designed that, quite often, the particular FPAI did “anything but family planning” – it began projects ranging from reforestation to road-building.

Linking family preparing with a holistic agenda of education, skill development and health, Wadia and the girl team employed creative communication techniques like singing bhajans (devotional songs) along with social messaging plus organising a family planning exhibition which zipped across the country by teach.

FPAI’s revolutionary style of work fostered public confidence plus led to marked enhancements in development signals.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty

For instance, a project which usually began in the 1970s in Malur within Karnataka, resulted in reduced infant mortality, a substantial increase in the average associated with marriage, and the doubling of literacy rates. The project evoked such popular assistance that villagers took over its management after FPAI exited the particular scene.

Perhaps due to her international upbringing, Wadia brought a global perspective to Indian family planning.

Inspired by the achievement of South Korean mothers’ clubs, which bolstered widespread approval of family planning in rural locations, she organised close-knit groups where females could discuss pushing social issues ranging from dowry to feminine under-representation in politics. At the same time, she grew to become a leading figure within the International Planned Motherhood Federation (IPPF), spotlighting the unique challenges faced by India within controlling its ballooning demographics.

Politics additional complicated these challenges.

During the Emergency, which was imposed through 1975 to 1977, the Indian government adopted draconian inhabitants control measures including forced sterilisation. Wadia condemned this, caution against coercion in family planning programmes and declaring that participation had to be strictly voluntary. Family preparing was beginning to display good results but , she lamented, the Crisis “brought the whole programme into disrepute. inch

In the early eighties, Wadia faced another formidable challenge as president of the IPPF. She locked horns with the administration people president Ronald Reagan, which cut funding from the country to the organisation which offered or endorsed child killingilligal baby killing services.

Even though the IPPF did not formally promote abortion, several of its affiliates supplied abortion services within countries where it was legal.

Courtesy FPAI

The IPPF refused to give into US stress to change this set up, resulting in a loss of $17m in funding to its programmes.

Wadia ridiculed the Reaganite notion that will free market economics would combat populace growth. Anyone who thought that, she averred, “has never been anywhere in the establishing word – you can find too many of the absolute poor, and you just can’t keep it to laissez-faire”.

In many ways, Wadia’s profession is of pressing meaning to contemporary issues in family preparing.

In the United States, very conservative have argued the reversal of abortion rights in Roe sixth is v Wade should be followed by reconsideration associated with rulings on contraceptive access .

Wadia – who had been involved in conceptualising India’s own abortion regulation – worried about just how abortion could be weaponised in a larger motion against birth control. “Those who try to mistake the public by equating abortion with household planning, ” she argued, “are trying to destroy human and individual rights. ”

Today in Indian, political debates are plentiful about employing disincentives plus coercive elements to restrict the sizes of families. Wadia cautioned against such approaches.

“We cannot assistance disincentives which usually do not uphold basic human rights, ” the lady said in 2k, when Maharashtra state – in a bid to enforce the two-child norm : considered stripping any kind of third-born child associated with food rations and free primary education. “In practice, anyhow, we have found that will disincentives don’t function. ”

These events have demonstrated that family planning is definitely intrinsically linked to law and politics. Maybe it was fortuitous, consequently , that India had a pioneering female attorney as one of the principal architects of its family preparing movement.

Above all, Wadia’s career is a tip that family planning cannot be divorced through overall socioeconomic advancement.

A few years before Wadia’s death, MS Swaminathan – the man of science who led India’s Green Revolution, which helped the country obtain food security : paid tribute to this fact.

“More than anybody else, ” he mentioned, Wadia “knew that if our population plans go wrong, nothing else may have a chance to go right”.

Parinaz Madan is a lawyer plus Dinyar Patel is really a historian.

-

-

14 November 2014

-

-

-

11 November 2014

-