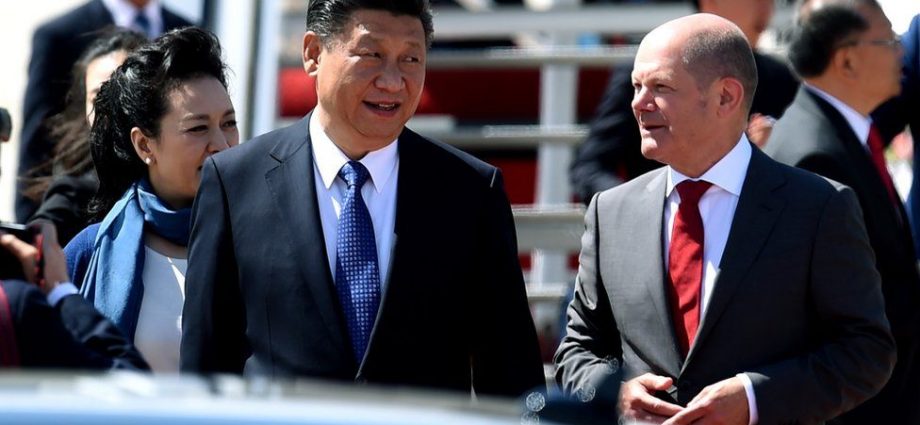

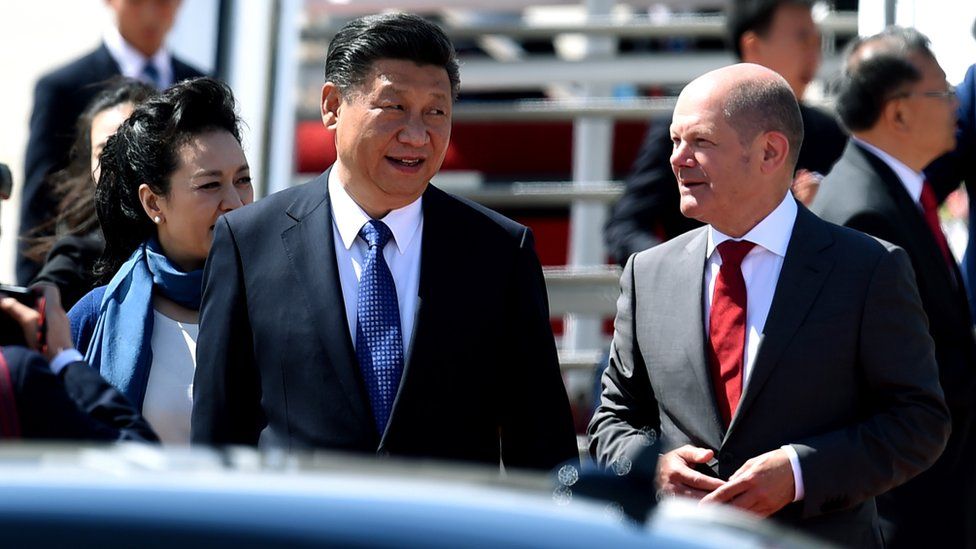

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz holds talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Friday, the first G7 leader to visit Beijing since the Covid-19 pandemic.

But his trip has sparked controversy in Germany and concern elsewhere in Europe.

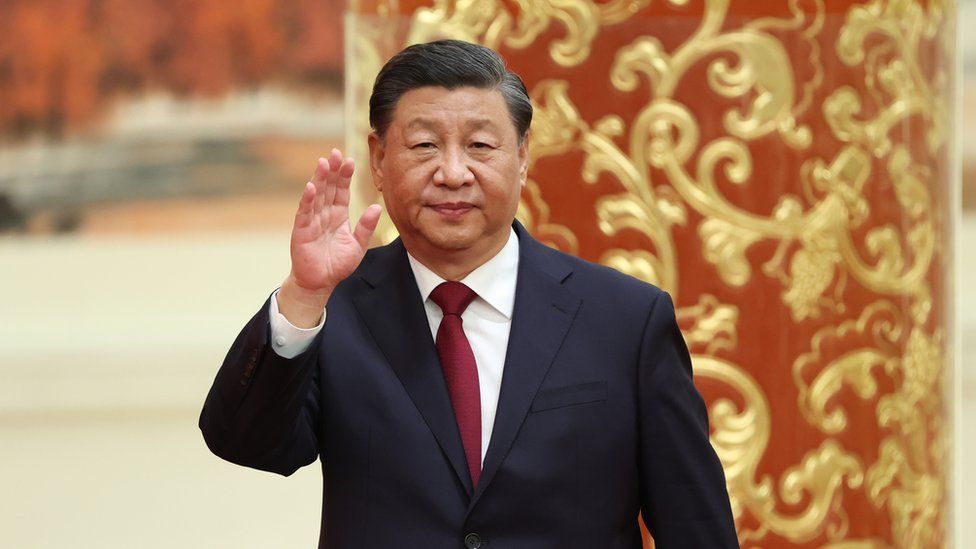

It comes hard on the heels of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party.

President Xi used it to tighten his grip on power, packing his leadership team with allies.

An extraordinary and bitter row erupted recently at the very top of the German government, when it emerged a Chinese company was poised to buy a significant stake in a part of the port of Hamburg.

No fewer than six government ministers reacted furiously. The deal, they argued, would give China significant influence over critical German infrastructure. Germany’s security services also urged caution.

But the German chancellor appeared insistent the deal should go ahead. He reportedly pushed through an agreement, albeit one that limited the size and influence of the 24.9% stake.

No-one is quite sure why he seemed so determined. A former mayor of Hamburg, Mr Scholz remains close to the city authorities who argued that the deal represented vital investment.

But plenty of other commentators suspect an ulterior motive; that Olaf Scholz did not want to turn up in Beijing without a “gift” for Xi Jinping.

That has raised both eyebrows and concerns.

We will seek co-operation where it lies in our mutual interest, but we will not ignore controversies… When I travel to Beijing as German chancellor, I do so also as a European

As has the chancellor’s decision to take with him a delegation of German business executives. That was standard practice for his predecessor, Angela Merkel, who pursued a policy of “Change through Trade”, believing that economic ties could influence political relations with countries like China and Russia.

“The signal that’s being sent is that we want to extend and intensify our economic co-operation – that must be questioned,” says Felix Banazsak, a politician from the Green Party, a partner in Mr Scholz’s coalition government.

The Greens have long sought a tougher line on China. Just a few days ago the party’s foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, sternly and publicly reminded him that his government came to power promising to readjust its China strategy.

Mr Banazsak says his country must learn from its previous dependence on Russian energy: “We must make ourselves as independent as possible from individual states, particularly if these are states which do not share our values.”

But Olaf Scholz will be painfully aware of the complexity and depth of his country’s ties with China, which remains Germany’s largest trading partner, although Germany imports more than it exports.

More than a million German jobs depend on that relationship. Take as an example car giant Daimler, which sells more than a third of its vehicles in China.

In the first half of this year, German businesses invested more in China than ever before. Chemical company BASF has just opened a new plant in south China and expects to invest €10bn (£8.6bn; $9.9bn) in the site by the end of this decade.

On the eve of the visit, the head of the German Automotive Industry Association pointed to Germany’s reliance on China for raw materials and warned that “de-coupling” would be an economic and geo-strategic mistake.

Her counterpart at the Association of Small and Medium Businesses also advised against a sudden change in course, saying “the advice can only be not to smash any Chinese porcelain now”.

Chancellor Scholz will spend less than 12 hours in Beijing. His aim, he said ahead of his journey, was to find out how much co-operation was still possible – because “the world needs China” in the fight against the global pandemic and climate change.

“If China is changing, then our approach to China must change,” he said.

Many in Berlin and beyond will be looking for evidence of that. Mr Scholz’s response to a shifting China may yet come to be the defining test of his chancellorship.

Scholz trip ruffles feathers in Europe

Germany is the EU’s most powerful economy and arguably most influential member, so what it says and does matters.

I once suggested former Angela Merkel could be viewed at times like a European Donald Trump for the way she tended to put Germany first.

Wider EU concerns were ignored in favour of lucrative German energy and trade contracts with Russia and China. She demanded EU austerity measures for Mediterranean member states during the eurozone crisis to protect German taxpayers from incurring shared debt.

Olaf Scholz is Mrs Merkel’s successor in far more than just name, in the minds of many EU leaders.

His massive aid package to help German businesses with high energy prices is viewed as giving them an unfair competitive advantage on the European single market.

And his trip to China, announced but not co-ordinated with others in the EU, has ruffled feathers Europe-wide. France’s Emmanuel Macron recently warned Mr Scholz he risked becoming isolated.

As Europe, and Germany first and foremost, weans itself off its dependency on Russian gas, the question is this: Is Berlin, blinded by the prospect of business deals, binding itself too close to China?

French President Emmanuel Macron has been pushing for years for the EU to become less beholden to Beijing. Critics accused him of protectionism.

But after global supply-chain breakdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic, the “weaponisation” of energy imports/exports after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Donald Trump’s presidency, it became clear Europe should no longer rely so heavily on the US in terms of security.

With Mr Macron’s insistence on the continent becoming more cohesive and self-reliant, diversifying its trade partners began to seem sensible to Brussels. Olaf Scholz is viewed as worryingly out of step.

-

-

26 October

-