Commentary: Hong Kongâs Messi backlash says more about digital fandom than football

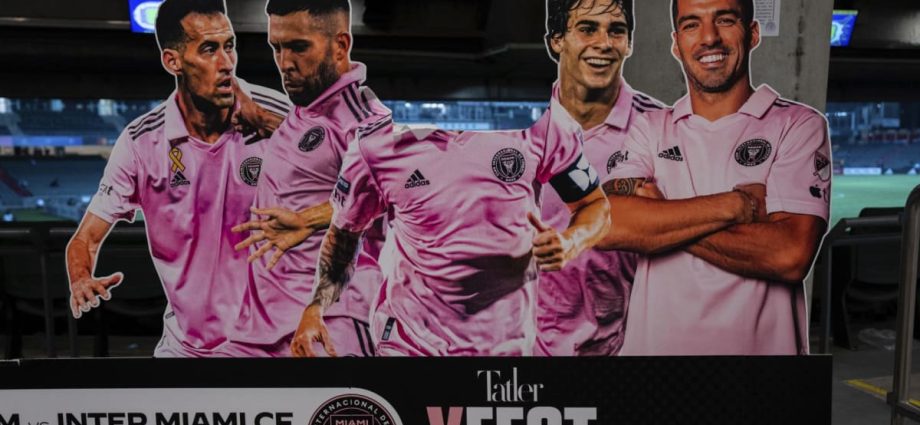

Key to this is where end-of-career Messi has wound up. Inter Miami football club, which is co-owned by David Beckham, was founded in 2018 and began playing in America’s Major League Soccer two years later as a flamingo pink baby of the TikTok/Instagram Reels/YouTube Shorts epoch.

It gets that live audiences will pay to watch Messi not just for his football, but for his Instagrammable presence. It also gets that his astonishing goalscoring prowess in a weaker league will create the sort of “Messi scores three times in five minutes” incidents which social media hungrily regurgitates.

Football, as a sport, has been adapting with varying degrees of success and urgency to the pressures and incentives created by these new delivery channels: Inter Miami is a pure confection of them and Messi, in theory, the ultimate sweetener.

HEROICS OF INDIVIDUAL FOOTBALL STARS

The issue that football (along with other sports) confronts is one of ever more aggressive fragmentation of diversion. The short video form, and the algorithms that push them with such addictive force, is arguably evolving faster than any other form of entertainment in history.

It is a turbocharged thief of time. Its power to distract and absorb is infinite: Not only is the format a perfect medium for delivering the new content that thousands of people delight in producing; it is also able to repackage existing content (snippets from films, TV, games, sport) in a way that can make something you’ve seen several times seem new.