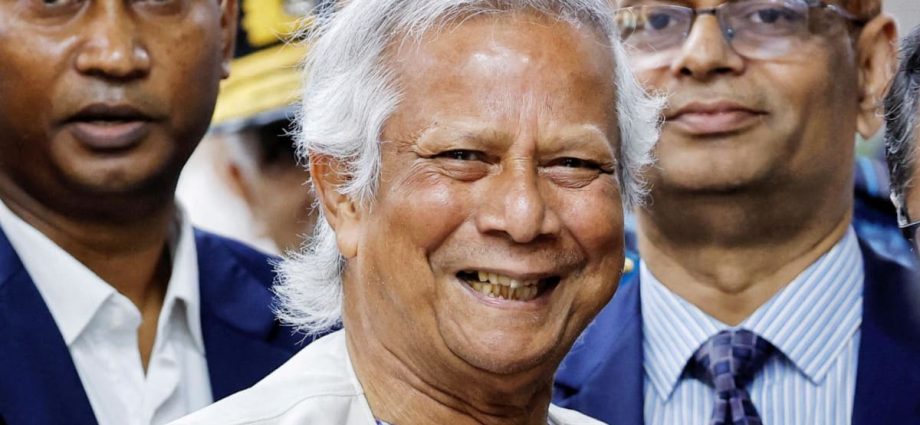

PM Wong congratulates Bangladesh’s Muhammad Yunus on taking charge of interim government

In his welcome email, Mr. Wong wrote,” I would like to thank you and wish you the best of luck with your appointment as the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.” Your time government has stubbornly taken the crucial work of restoring balance in this period of transition. ”Continue Reading