For the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic began, Chinese President Xi Jinping has left China to visit Kazakhstan and then Uzbekistan for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit.

This is in contrast to previous reports of Xi’s potential travel to Saudi Arabia or speculation that Xi’s first foreign travel would be to Indonesia for the G20 summit. Besides China, the SCO includes Russia and India as full members and Iran as an observer seeking full membership – along with multiple Central and South Asian members.

Xi’s choice to visit Uzbekistan and participate in the SCO summit in person indicates Beijing is primarily focused on bolstering stability at home instead of power projection in East and Southeast Asia.

However, the Biden administration’s democracies versus autocracies rhetoric could help transform the SCO from a primarily counterterrorism and internal stability organization into a more cohesive international grouping capable of challenging US interests abroad.

Xi’s first foreign visit in nearly three years to participate in the SCO summit demonstrates Beijing’s focus on internal security rather than power projection. Before the SCO’s founding declaration was issued, the original members created the Shanghai Convention on Combatting Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism.

Given this document’s status as a pillar of the SCO, Xi’s visit shows Beijing believes terrorism and separatism – particularly in Xinjiang and Tibet – remain a significant threat to China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

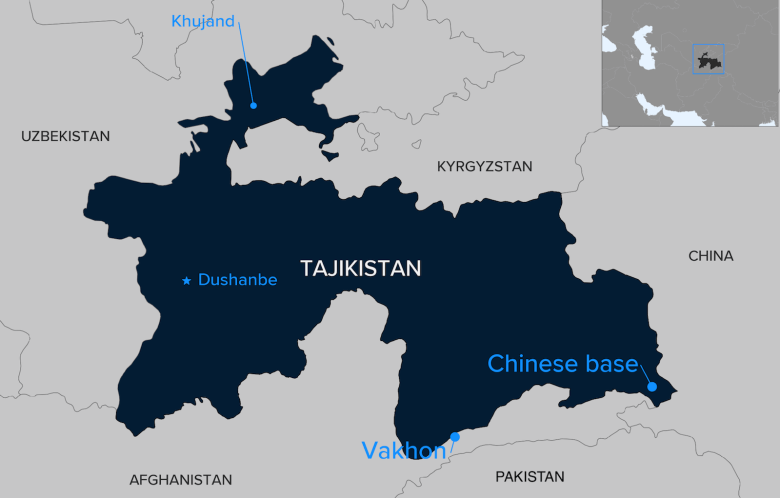

Xi likely believes the threat will remain significant in light of increased Western criticism of China’s human rights abuses in these regions. By reinvigorating China’s relationships with its Central Asian partners, Xi may help reduce external support for any separatist and terrorist groups in Xinjiang and other minority areas.

In the same light, Xi’s SCO visit gives him the opportunity to meet with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and improve – even if marginally – Sino-Indian ties and border stability. A meeting between the leaders would build upon recent de-escalation of border tensions after years of troubles and put territorial dispute negotiations back on a more stable track.

It could also signal Beijing’s effort to pry New Delhi away from the Quad – although this will be a Herculean undertaking. Regardless, progress on border stability and China-India relations would allow Beijing to concentrate on other more pressing foreign policy priorities.

Equally important to boosting territorial integrity and border stability, Xi’s first pandemic foreign visit to the SCO summit indicates China is concerned about access to energy and food resources. Without secure access to energy, the Chinese economy will be hindered.

Over the past two years, supply shortages, heatwaves, and drought have cut into China’s domestic energy production. Likewise, this year’s drought may harm its agriculture sector and overall food security. Since 2021, Beijing has prioritized food security with Xi calling it essential for national security.

But it is much more than that. Similar to energy’s importance to the economy – and thus the CCP’s legitimacy – feeding the population has been a core factor for any Chinese government’s legitimacy. Xi’s direct participation in the SCO summit could help shore up China’s energy and agriculture imports from Central Asia, Russia, and Iran.

The BRI may also be reinvigorated and see new pledges – although China’s current economic situation will make these more rhetoric than reality. Regardless, Beijing will seek to continue the BRI’s successes.

China views continental Asia’s economic and infrastructure development as essential to national security. These areas will be critical pillars for trade and movement of resources should China be cut off from the Pacific Ocean.

For now, Xi’s efforts may work best during bilateral meetings at the summit, but the Biden administration’s democracies versus autocracies rhetoric risks transforming the SCO from a relatively benign organization into a more substantive body.

SCO members are no paragons of democracy. Even India has its challenges. A strong and active SCO united in fear of US regime change operations could pose a threat to US interests across the globe and represent a major foreign policy failure.

It would effectively control the Mackinderian Heartland and further unite China and Russia against the United States. This would weaken Washington’s ability to defend and advance its vital interests.

Additionally, should New Delhi develop a stronger affiliation with the organization, the SCO would have a strong position across the entire Asian continent with Beijing likely first among equals.

US policy should consider the meaning of Xi’s first foreign visit in years and adjust accordingly. China is showing its inability to pose an imminent and immense threat to the US and its allies’ interests in the Indo-Pacific region.

Beijing is constrained by domestic stability concerns, border issues, and insufficient energy and food supplies. Instead of pushing for de facto containment and risking a united authoritarian axis against America, Washington should use restraint and take the extra time it has to develop a real China strategy with an end goal and realistic means.

Quinn Marschik is a Contributing Fellow at Defense Priorities